Reply to a Paper Historian

Introduction

Pierre Vidal-Naquet is professor at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (School for advanced studies in the social sciences) in Paris and has been a very determined adversary of mine. He has attacked me in the academic and journalistic spheres and even in the law courts. Along with Léon Poliakov he is author of a declaration, published in Le Monde of February 21, 1979, p. 23, that was signed by 34 historians:

One must not ask oneself how, technically, such a mass murder was possible. It was possible technically, since it happened. That is the compulsory point of departure for any historical inquiry on this subject. It was our responsibility to recall this truth in simple terms: there is not, there cannot be any debate about the existence of the gas chambers.

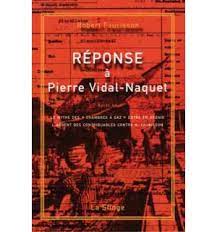

P. Vidal-Naquet is also the author of a long article directed against me entitled “Un Eichmann de Papier” (A Paper Eichmann). I replied to that article with my own Réponse à un historien de papier (“Reply to a Paper Historian“). Vidal-Naquet’s article first appeared in the monthly Esprit (no. 45, September, 1980, p. 8-52), and later in a new form, with additions, in a book entitled Les Juifs, la mémoire et le présent (Maspero, Paris 1980, p. 195-282).

My reply first appeared in a short book entitled Réponse à Pierre Vidal-Naquet (La Vieille Taupe, Paris 1982) and then in a second, expanded edition in December 1982. It appears here for the first time in English.

An abridgement of the Vidal-Naquet article has been published in English (Democracy, April 1981, p. 67-95) but I have not checked to see whether the translation is faithful to the original. Vidal-Naquet is quite hard-hitting and even insulting, but his article is interesting and even unique: for the first and last time an exterminationist has tried to answer the arguments of a revisionist. When the revisionist replied to the exterminationist, the latter abandoned the discussion and retreated into silence. Vidal-Naquet no longer talks about gas chambers.

In France there have been two other attempts to answer the revisionists’ arguments, but they were so weak that they collapsed under their own weight. The first was by Nadine Fresco (“Les Redresseurs de morts” [The adjusters of the dead], Les Temps Modernes, no. 407, June 1980, p. 2150-2211) and the second by Georges Wellers (Les Chambres à gaz ont existé [The gas chambers existed], Gallimard, Paris 1981).

Since the resounding defeat in their French ventures the exterminationists have preferred not to cross swords with the revisionists. Two recent examples illustrate this: first, the collective work directed by Eugen Kogon, Hermann Langbein and Adalbert Rückerl (NS-Massentötungen durch Giftgas [NS mass killings with poison gas], S. Fischer, Frankfurt-am-Main 1983); then, Raul Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews, revised and definitive edition (Holmes and Meier, New York/London 1985). In neither book are the names of the revisionists mentioned, or their publications or arguments cited. For a book to be considered scholarly, however, it must treat both sides of the issue at hand, present the arguments of the opposing side, furnish bibliographical information that would enable readers to consult the original sources; and, finally, it must, if it can, reply to the opposing party.

One of the most notable differences between the exterminationists and the revisionists is that while the revisionists spend most of their time citing and examining the arguments of the other side, the exterminationists maintain a policy of ostracism against their opponents.

Let us imagine for a moment a layman who would like to know who are right – those who claim there was a genocide carried out against the Jews with the use of homicidal gas chambers or those who claim that this is a historical lie. Such a layman would like to attend a debate between representatives of the two theses, but he cannot. The exterminationists refuse all proposals for debate that the revisionists offer. In place of attending such a debate, this layman might want to read publications in which each side tries to answer the other’s arguments. But he cannot do this either, because while the revisionists do discuss the opposing arguments, the exterminationists either turn a deaf ear or reply with insults.

There is only one way to satisfy, to some extent, our layman’s desires; that is to have him first read Vidal-Naquet’s A Paper Eichmann and then my own “Reply to a Paper Historian”. Failing that, “Reply to a Paper Historian” offers an introduction to a debate between an exterminationist and a revisionist that is unprecedented, both in its scope and its detail.

***

The historian cannot avoid spending a good part of his life amid paper. He searches through, gathers, compares archives and written documents of all kinds. But at the same time he must not neglect the material aspect of facts; he also at times turns into a field-worker, an explorer, archaeologist, physicist, chemist. Going to the spot, he sees, probes, measures, photographs; he touches things with his fingers. He sometimes turns into a police investigator; he proceeds with physical reconstructions or, when that is impossible, he prudently reconstructs things in his mind. He needs to have his feet on the ground. It is quite fine for him to inform himself from papers about what democracy in Rome was, but it is wise to go to the spot in Rome to see what a small area was covered by the Forum, the shrine of that democracy. Illusions fly away: too bad! Reality replaces them: so much the better!

When he deals with the Ancient World, which is his speciality, Pierre Vidal-Naquet, I suppose, is not content with papers but goes to the spot.

On the other hand, when he improvises as historian of the “gas chambers,” he stays amid documents and abstractions. Installed far above us in a half-philosophical, half-religious empyrean, he writes about other writings and does not even take care to reflect on what he writes. That is why I call him a paper historian.

From the very first paper he wrote on the question of the “gas chambers,” one discovers two striking examples of this grave distortion of the mind. As I have mentioned above, Le Monde (February 21, 1979, p. 23) had published a text entitled “The Nazi policy of extermination: a declaration of historians.” That text was written by Pierre Vidal-Naquet and Léon Poliakov and signed by thirty-four historians with no competence in the subject.

To begin with, the Le Monde text reproduced an extract from the “confession” of SS-Obersturmführer Kurt Gerstein. This extract was meant to persuade us that it was an “unquestionable” and “striking” testimony about the Nazi “gas chambers.” In a halting French Gerstein had, we are told, written: “The naked men [in the gas chambers] stand at [sic] the feet of the others. Seven hundred to eight hundred in 25 square metres, in 45 cubic metres; the doors are closed.” Any reader attentive to reality would conclude: “28 to 32 men standing in one square metre: there we have something that is materially inconceivable; the admissibility of this strange testimony is, at the least, subject to caution.”

But, installed in their philosophical-religious empyrean, our thirty-four scatterbrains had not seen what leaps to the eye of the layman.

Here again is the conclusion – triumphant, and silly, and vacuous – of our paper historians’ manifesto:

One must not ask oneself how, technically, such a mass murder was possible. It was possible technically, since it happened. That is the compulsory point of departure for any historical inquiry on this subject. It was our responsibility to recall this truth in simple terms: there is not, there cannot be any debate about the existence of the gas chambers.

Tautology? Reduplicate pleonasm? Sheer dull-wittedness? How can one qualify a pearl of such fine lustre? Mark the end of that last sentence: “there is not, there cannot be, any debate about the existence of the gas chambers.“ In good logic, Vidal-Naquet would not, nineteen months later, have had to publish in Esprit a long article on the subject, later published in the aforementioned book Les Juifs, la mémoire et le présent, that he expected me to honour with a reply (p. 280). Here is the explanation: the text in Le Monde was conceived to attend to the most urgent things first; in the disarray brought on by my article on The Rumour of Auschwitz, Vidal-Naquet and Poliakov hastily drew up a manifesto and then took it to prospective signers, telling them: “We’re saying that there can’t be any debate, but it’s obvious that each of you must ignore that sentence and that each of you must get to work replying to Faurisson.“ That is what Vidal-Naquet artlessly admits on page 196 of Les Juifs… when he writes:

A good number of historians signed the declaration published in Le Monde of February 21, 1979, but very few got to work, one of the rare exceptions being F. Delpech.

As to the argumentation that might be hiding behind the dull-wittedness, I shall leave it to others to answer. Here I give the floor to Claude Guillon and Yves le Bonniec (Suicide, mode d’emploi, Alain Moreau, Paris 1982):

We are quite prepared, for our part, to consider any method of elimination, including gas chambers. It is possible that Faurisson’s technical arguments will be shown to be worthless. That said, it is inevitable to ask oneself how, technically, the gas chambers function, that is, simply, if they exist or existed. Such is the obligatory course of every historical inquiry. If, by any chance, there were no-one to show how a single gas chamber was able to function, we would deduce that no-one could have been asphyxiated in it (p. 205).

That remark of the two authors is preceded by the following:

After Rassinier (whose assessment of the gas chambers is more nuanced), Faurisson is interesting for having, at the same time that he claims to denounce a forty-year-old lie, actually revealed numerous lies, and having aroused among his opponents one of the decade’s most formidable productions of new lies. The official historians themselves recognise that at the place where, still today, people are admitted to visit a gas chamber, there never was one – a fact that ought not, according to them, to diminish at all the credit accorded to other “historical” truths. (op. cit., p. 204-205)

Claude Guillon and Yves le Bonniec use there a CAPITAL argument of the revisionists against the exterminationist thesis. Vidal-Naquet does not breathe a word of this argument in his innumerable writings and interventions: I want to speak about what I call the “drastic revision” of August 19, 1960. On that day the Hamburg weekly Die Zeit, accommodating towards the theses of the winners of the last war, published a letter, a simple letter from Dr Martin Broszat of the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich. In that letter, restrictively entitled “No Gassing at Dachau,” it was conceded to us or, rather, it was finally conceded to the historical truth that there had been no homicidal gassing anywhere in ALL OF THE OLD REICH (Germany within its 1937 frontiers). Since 1960, that is, for 22 years, we have awaited the rigorous, documented study that would let us see, at one and the same time, why it suddenly became necessary to stop believing in the “gassings” of Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück, and Neuengamme but to continue believing in the “gassings” of camps located in communist Poland. Did we not have at our disposal for all those camps, without distinction, a mass of “proofs,” “testimonies” and “confessions”? Had the authorities not executed or driven to suicide men who had been in charge of camps where, eventually, it was revealed, as if by the working of the Holy Spirit, that there had never been the least homicidal “gas chamber”? But enough of this naivety: if Dr Broszat, who in 1972 became director of his institute, has never dwelt on these questions it is because he knows perfectly well that in showing the inanity of the “proofs,” the “testimonies” and the “confessions” relating to the camps located in the Old Reich, he would demolish, at the same time, the “proofs,” the “testimonies,” the “confessions” relative to the camps in communist Poland. For, to an honest observer, all those “proofs,” all those “testimonies” and all those “confessions” are the same: they are of no real interest except for those sociologists who study the mechanisms of belief.

I now come to the article by Vidal-Naquet. I am going to follow it step by step at the risk of appearing desultory or of repeating myself, for the whole is confused.

1. From page 195 to page 208 Vidal-Naquet piles up generalities and digressions that seem to me to be without great relevance to the subject.

Response: No response.

2. From page 208 to page 210 Vidal-Naquet talks about “Himmler’s secret speeches” (Discours secrets, Gallimard, Paris 1978), about the statistician R. Korherr and about the German word Sonderbehandlung (special treatment). He insinuates, but with no great conviction, that a passage from the speeches shows a will to carry out “genocide” against the Jews and that Sonderbehandlung is a code word for extermination.

Response: I will first make a remark on the enticing title, “Secret Speeches”. There is nothing secret about those speeches! In this regard I note a clear tendency among the exterminationists to fool the good reader with tendentious titles: so it is that Serge Klarsfeld gives the title Mémorial à la Déportation des Juifs de France to what is but a list of Jews who were put on the trains for deportation. This is not a list of dead as is often given to understand, especially when such lists are plastered on a funerary monument near Jerusalem. Georges Wellers, in his hatred for Vichy, goes so far as to entitle one of his books L’Étoile jaune à l’heure de Vichy (The yellow star in Vichy times), whereas the Vichy government always opposed, and successfully, the measure obliging Jews in its zone to wear the yellow star. Vidal-Naquet, for his part, does not know in what tone one should take Himmler’s remarks to have been meant. He speaks of his “direct or almost totally direct language.“ Here, he believes he sees him “at maximum frankness,” although, he adds, “a description of the real process would be a thousand times more traumatising.” There’s the rub for him – Vidal-Naquet proclaims that he has found in Himmler what the exterminationist historians have sought in vain since 1945: either an order or a simple instruction proving the will to exterminate the Jews. But at the very moment when he presents the result of his hunt, behold him pouting before what he has found: Himmler’s language is “direct or almost totally direct,” there is no “description of the real process”… We might ask whether, by any chance, that “description of the real process” existed only in Vidal-Naquet’s head. That’s not all. Vidal-Naquet adds another puzzle to the puzzle. He is surprised at an “attenuation” by Himmler. Hell, Himmler was speaking before an “informed” audience! Why, then, this “indirect or almost totally indirect” language? Then, suddenly, locking himself in an ever more abstract and autistic analysis, Vidal-Naquet believes he has discovered that Himmler is “coding”… and even “over-coding”. Vidal-Naquet deciphers this alleged “code” with sovereign speed and ease; he draws it from his breast-pocket, from out of his head. He decrees, without the least argument, that Sonderbehandlung of the Jews is a codeword and, right before our eyes, he decodes it instantaneously: the word means “extermination.” But where things become complicated is when our analyst, seized by a sudden scruple, adds in a note this remark quite likely to mislead a reader who, as things are, no longer knows whether Himmler is “direct or almost totally direct”, whether he “is at maximum frankness” or is being secretive, whether he “codes” or whether he “over-codes”: “Of course Sonderbehandlung could also have a perfectly benign meaning.”

The reality of it was the following: Sonderbehandlung could have a whole series of meanings, from the gravest to the most benign. The context clarified things for the reader. The first meaning seems to be medical, and one will find, for example: Sonderbehandlung: Quarantänelager (quarantine camp). On the other hand, in document PS-502, the same word means explicitly Exekutionen (executions). Sonderbehandlung could apply to the favourable treatment enjoyed in captivity by dignitaries. See what defendant Kaltenbrunner says about this before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg (Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal – IMT –, Volume XI, p. 339):

Especially qualified and distinguished personalities were accommodated there [i.e., the two luxury hotels Walsertraum and Winzerstube – ed.] – I would mention M[onsieur] Poncet and M[onsieur] Herriot and many more. They had three times the normal ration for diplomats, which is nine times the ration of the ordinary German during the war. They were daily given a bottle of champagne. They were allowed to correspond freely with their families in France and to receive parcels. These internees were allowed to receive visits on several occasions, their wishes were cared for wherever they were. That is what is meant here by “special treatment”.

Arrivals and departures were identified in the daily reports on the population of each camp. Among the departures there might be: the dead, the “S.B.” (= Sonderbehandlung), the freed (one forgets that a good number of Auschwitz inmates could leave after having served a sentence of a few months), the transferred. We are expected to believe that the “S.B.” were persons condemned to “gassing.” There were, however, “S.B.” in the camps that, even according to the exterminationist vulgate, had no gas chambers. These “S.B.” must therefore, in all likelihood, have been internees assigned to other camps for a given reason (that of health for Bergen-Belsen, the category of Jews to be exchanged with the Allies also for Bergen-Belsen, women for Ravensbrück, Dachau for priests, the aged for Theresienstadt, etc.). The “transferred” category proper was made up of persons assigned to a particular job either in a camp or in a distant factory. Found in the travel authorisations are telegrams from the WVHA (SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt, in English: the SS economic and administrative central office) allowing trucks to go fetch material either for Sonderbehandlung or for Desinfektion, these two words being used interchangeably. It was a matter, more precisely, of going to Dessau to fetch quantities of Zyklon-B in order to carry out disinfection of the Auschwitz camp, where typhus reigned (radio message of July 22, 1942 addressed to the Auschwitz camp under the signature of General Gluecks [Raul Hilberg, Documents of Destruction, Quadrangle Books, Chicago 1971, p. 220]). In one and the same book (Sachso, Amicale d’Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen, Coll. Terre Humaine, Minuit-Plon, Paris 1982) the expression “special treatment” is applied, on page 99, to the making of a mark in blue pencil on the left breast of a bearer of lice and, on page 327, to an execution.

When seeking an expression that might account for all these meanings at once, one wonders: mightn’t the most suitable for Sonderbehandlung be “to isolate”? That meaning is encountered in gesonderte Unterbringung (isolated stay), an expression often applied to persons arriving.

The fact remains that since Sonderbehandlung could possibly mean “to execute”, it is quite understandable that Himmler, after receiving his statistician Korherr’s report, should have had the latter instructed to replace, in such or such passage of the text, the word Sonderbehandlung with Transportierung (transport).

Long after the war Korherr, furthermore, was to protest against the interpretation of Sonderbehandlung as signifying “massacre”. In Der Spiegel of July 25, 1977, cited by Dr Wilhelm Stäglich on page 391 of Der Auschwitz Mythos (Grabert Verlag, Tübingen 1979; English translation: Auschwitz: A judge looks at the evidence), he wrote:

The statement according to which I supposedly was able to establish that more than a million Jews could have died in the camps of the General Government in Poland and of the territories of the Wartheland as the result of a special treatment (Sonderbehandlung) is absolutely inaccurate. I must protest against the use of the verb “to die” in this context.

Korherr goes on to say that Sonderbehandlung was supposed to mean Ansiedlung (displacement).

The context is indeed the last concern of a Vidal-Naquet. I readily concede to him that on page 168 of the French edition of “Secret Speeches” (Discours secrets), Himmler says this to his audience:

The following question was put to us: What to do with the women and children? I made up my mind and here again found an obvious solution. In effect, I did not feel I had the right to eradicate the men — say, if you will, to kill them (!) or have them killed — and allow the children to grow up into adults who would avenge themselves on our children and on our descendants. The grave decision to make this people disappear from the earth had to be taken.

If we end the quotation here, as Vidal-Naquet does, Himmler assumes the proportions of a General Turreau [in Revolutionary France] intent on killing the men, women and children of the Vendée region and making it a great cemetery. However, the following part is curious and gives one to understand that Himmler was indulging in a bit of braggadocio. He says, in effect, that in the implementation of his solution he has been able to avoid a double danger for German officers and soldiers:

… that of becoming too hardened, of becoming heartless and no longer respecting human life, or of becoming too soft and losing one’s head to the point of nervous breakdown – the course between Scylla and Charybdis is terribly narrow.

But then, one will ask, how did Himmler’s men actually proceed? The answer is found on many pages of his so-called secret speeches and, in particular, pages 204, 205 and 206.

Two months after the talk quoted above Himmler returned to the subject. Again, it is the partisan war that he is talking about, a war waged savagely on both sides. He says:

When I was obliged to take action in a village against the partisans and Jewish commissars – I’m saying this to this circle, as meant exclusively for this circle – in principle I also gave the order to kill the wives and children of those partisans and commissars as well. I would be a coward and a criminal towards our descendants if I allowed the hate-filled children of those sub-humans slaughtered in the struggle of man against sub-human to grow up. Believe me: this order is not so easy to give or to carry out, it’s easier to conceive and express in this hall. But we must always be conscious of the fact that we find ourselves in a primitive, basic and natural struggle. (p. 201)

More interesting yet is the speech Himmler gave five months later before some generals at Sonthofen. Here one finds less than ever the “genocide” that might be feared. He declares:

I considered that I did not have the right – this concerns the Jewish women and children – to allow children to grow up into adults who would later seek to avenge themselves and would kill our fathers [sic!] and our children. I consider that that would have been cowardice. Therefore the problem has been solved without compromise. At present – it’s exceptional in this war – we are bringing 100,000 Jews from Hungary to the concentration camps, and later we’ll bring another 100,000 to build underground factories. But none of them will come into the German people’s field of view.

The Germans were haunted by the possibility of new uprisings behind their lines like that of the Warsaw ghetto. Concerning the fear of seeing happen at Budapest what had happened in Warsaw one may read Ich, Adolf Eichmann (I, Adolf Eichmann), published by Dr Rudolf Aschenhauer (Druffel Verlag, 1980), page 33.

3. On page 211 Vidal-Naquet, reciting the history of the “extermination,” speaks of “the halt to the extermination of the Jews on Himmler’s order at the end of October 1944.”

Response: That order never existed and I challenge Vidal-Naquet to produce it for us. Just as there existed no order by Hitler or by Himmler or by anyone to start the extermination of the Jews, so also was there no order by anyone to stop an extermination that had not been taking place.

4. In a footnote on page 212 Vidal-Naquet asserts: “I see no reason to doubt the existence of the gas chambers at Ravensbrück, Struthof, and Mauthausen.”

Response: With regard to Ravensbrück, Vidal-Naquet refers us to the book by Germaine Tillion (Ravensbrück, Le Seuil, Paris 1973), which contains a plan of the camp. The location of the alleged “gas chambers” is not even noted; moreover, there is neither the least plan nor the least indication of a material order. This is a strictly metaphysical “gas chamber”.

As for Struthof, I was the first to publish the facts about the state of the buildings, guaranteed to be “in their original state”; and I proved that any “gasser” would have first gassed himself with his mysterious gas (see the two contradictory confessions of Josef Kramer). Vidal-Naquet does not solve the technical puzzle; besides, nothing that is technical interests him.

With regard to Mauthausen, things are even simpler: the operating levers for the tubes bringing the alleged gas into the shower are… at the victims’ disposal! This is something clearly evident from a normal photo: the photo featured at the recent exhibition on the deportation held in Trocadéro square in Paris (April-May of 1982) showed this much less well: the levers appeared as if filed down.

5. On page 212, in footnote 23, Vidal-Naquet confesses that there exists on the subject of the concentration camps “a whole sub-literature that represents a truly vile form of appeal to consumption and to sadism.” He adds: “All that derives from hallucination and propaganda must be eliminated.” For these reasons he denounces Christian Bernadac, Silvain Reiner, Jean-Francois Steiner and V. Grossman. He admits to having “fallen into the trap set by Steiner’s Treblinka (Fayard, Paris 1966)”.

Response: Fine indeed, but that hardly moves us forward. What would be instructive for the reader would be to know why Vidal-Naquet fell into such a trap and how he got out of it. He insults Bernadac without our knowing exactly why and he extols Nyiszli, without our knowing why either. He proceeds by ukases. He decrees that one story is credible and that another is not. He undertakes none of those analyses that the revisionists compel themselves to conduct. When a Rassinier tells us that Nyiszli’s best-seller Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Eyewitness Account is nothing but the “work of a scoundrel,” it is after a long analysis and an investigation of the most serious kind. Rassinier arms us for future readings that we shall be able, as adults, to make properly in order to distinguish the true from the false. Vidal-Naquet disarms us. In his presence we are like children who, each time a new book appears, await the judgment that will come from the mouth of their father – a father both peremptory and fallible. What does he think of Martin Gray who, to write Au nom de tous les miens (published in English as For Those I Loved), took as his ghost-writer a sermoniser named Max Gallo who helped Gray, in cooperation with the Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine de Paris (CDJC), to invent a stay at Treblinka? Does he savour a fragrance of authenticity in the rubbish piled up by Filip Müller in Trois ans dans une chambre à gaz d’Auschwitz (Pygmalion/Gerald Watalet, Paris 1980, 252 p.), a book launched in a blaze of publicity by Claude Lanzmann and Le Nouvel Observateur, a book that just about drew tears from the actor François Perrier when he went on television to mention it?

What does he think of Constantin Simonov on Majdanek (Éditions sociales, Paris 1946, 40 p.)? How does he judge a hundred other books, whether historical works or testimonies, in which one finds the same clichés, the same inventions, the same stenches, the same material impossibilities as in the works he denounces as fakes? What does he think of Fania Fénelon, between her descriptions of what she lived through at Auschwitz (which are not without interest) and her efforts to make us believe in the existence of the gas chambers (which she did not see)? What does he think of the quite recent book Sachso, in which the association of former inmates of Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen has the effrontery to tell us that that camp possessed a homicidal “gas chamber,” when for nearly a quarter of a century it has been accepted by the authorities in exterminationist history that the camp in question never had any such installation? What does he think, in this regard, of the way in which belief turns into science?

6. On pages 212-213 Vidal-Naquet concedes that the theologian Charles Hauter, who was deported to Buchenwald, “never saw a gas chamber” and “is delirious on the subject”. He quotes him:

The mechanism literally abounded when it was a matter of extermination. This, having to be done quickly, demanded a special industrialisation. The gas chambers answered that need in quite different ways. Some of them, of a refined style, were supported by pillars of a porous material, inside of which the gas formed and then passed through the walls. Others were of a simpler structure. But all were sumptuous in appearance. It was easy to see that the architects had designed them with pleasure, giving them their attention over a long time, bringing the resources of their aesthetic sense. They were the only parts of the camp built with love.

Response: I do not see why Vidal-Naquet recuses this testimony. It is neither worse nor better than anything else to be read on the subject of the “gas chambers” of Buchenwald, Auschwitz or elsewhere. By what right does Vidal-Naquet state that this theologian never saw any gas chambers, and that he “is delirious on the subject”? The answer is simple and disarming, like reasoning à la Vidal-Naquet, and must be formulated as follows: “This theologian did not see gas chambers at Buchenwald, for he offends the official truth on the question, official truth admitted by tacit and secret consent among the court historians, according to which, well, eventually, Buchenwald had no gas chamber.” In other words, to remain faithful to the tautological, pleonastic and autistic reasonings of a Vidal-Naquet, here is the answer that should be made to Charles Hauter: “One must not ask oneself how, technically, such a mass murder was not possible at Buchenwald. It was impossible technically, since it did not happen. That is the compulsory point of departure for any historical inquiry on this subject. It was our responsibility to recall this truth in simple terms: there is not, there cannot be any debate about the non-existence of the gas chambers at Buchenwald.”

7. On page 213 Vidal-Naquet concedes “The figure of six million Jews murdered, which comes from Nuremberg, has nothing sacred or definitive to it, and many historians arrive at a slightly lower figure.” So it is, he adds in a footnote, that “R. Hilberg arrives at a figure of 5,100,000 victims”.

Response: This remark of Vidal-Naquet concurs with what Dr Broszat was finally to declare before a court in Frankfurt: “The six million is a symbolic figure.” I am surprised that Vidal-Naquet does not quote a more convincing argument in support of his thesis than the figure proposed by Raul Hilberg. Gerald Reitlinger, for his part, on page 546 of his The Final Solution (Sphere Books Ltd., London 1971) presents a “Summary of Extermination Estimates (Revised 1966)”. This table gives us a choice between a minimum of 4,204,000 and a maximum of 4,575,000 Jewish deaths. Still, he does take care to add that these are totals based on conjectures. Vidal-Naquet ought to inform the reader that all the totals of Jewish deaths are based on pure conjecture. After 37 years and with the electronic means that we possess, the approximate total of Jewish victims could have been established some time ago but, unhappily, it so happens that the authorities do not want to supply the means to establish it. When a country like France has kept its own figures for nearly ten years now, it hides them for fear of Jewish reactions and, as will be seen further on, Vidal-Naquet has recently taken a personal part in this refusal to communicate information that, without question, would make the manipulators of figures and the liars uncomfortable.

8. On pages 213 and 214 Vidal-Naquet writes of Klarsfeld: “In the same way, Klarsfeld, by the detailed work that characterises his Mémorial, has lowered by more than 40,000 the figure usually given for the deportation of Jews from France (from 100,000 to a little more than 76,000).”

Response: I have just said what I think of the title of Klarsfeld’s book. The content is worthy of one of the photographs that appear on the cover. This photo is truncated in order to appear pitiful: the smiling people have disappeared. The photo can be found in its whole form on page 188. Second truncation: on page 28, Klarsfeld gives the reader to believe that General Kohl was an advocate of a physical annihilation of the Jews, whereas it was a question of annihilating their influence, “as of that of the political churches”. The words deleted are: “Er zeigte sich auch als Gegner der politischen Kirchen” (“He showed himself to be an enemy of the political churches as well.”) This very grave truncation of a text of [SS-Hauptsturmführer Theodor] Dannecker comes from Josef Billig, followed by Georges Wellers, followed by Michael R. Marrus and Robert O. Paxton. Each of them has replaced the missing sentence with three dots, the typographical sign of an omission. Each has thus been able to say: “Here at last is proof of the will to exterminate. The only proof, to tell the truth.” With Klarsfeld the truncation is all the more conscious as, before publishing his Mémorial, he had in 1977 published, for the German courts that were to try Kurt Lischka, Die Endlösung der Judenfrage in Frankreich (The Final Solution of the Jewish question in France; Deutsche Dokumente from the Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine, 245 p.). In that work it was impossible to make those three dots appear all of a sudden right in the middle of a letter by Dannecker (page 36). I can cite a third attempt at trickery on Klarsfeld’s part on page 245 of his Mémorial, in regard to the diary of Dr Johann-Paul Kremer: see my Mémoire en défense, p. 125.

But there is something infinitely more serious. In order to determine the number of dead among the 76,000 Jews deported from France, Klarsfeld has used an astonishing procedure: he has declared DEAD all those who had not taken the trouble to go and declare themselves alive at the Ministry for veterans’ affairs by the deadline of December 31, 1945! And this when that step was, on top of everything, neither compulsory nor official. Truth obliges me to say that Klarsfeld did go to Belgium to find out whether he might gather the names of some more survivors there. The majority of Jews deported from France were foreigners. I do not think they had a great desire to come back to a country that had handed them over to the Germans.

Klarsfeld has not bothered trying to learn how many Jews deported from France and later liberated from the camps went to settle in Palestine, the United States, South Africa, Argentina, etc. He has had no scruple about counting as dead all those who, after returning to France, presented themselves, without being asked to do so, at the door of the Ministry for veterans’ affairs after December 31, 1945. A great deal could be said about his Mémorial, about the Addendum to his Mémorial, about the thousands of “gassed” invented from nothing by the CDJC, and this by Klarsfeld’s own admission.

Vidal-Naquet says that the number usually given for Jews deported from France was 100,000 and that Klarsfeld reduced it to a little more than 76,000, thus bringing about a revision of some 40,000 (?). There is an error there. The number usually given was 120,000 and not 100,000, and therefore the revision is of about 44,000. For Klarsfeld, in 1939 France had about 300,000 Jews (French, foreign, stateless…) among its 39 million inhabitants (see his page 606). From this one will conclude that three quarters of the Jews settled in France were not deported; a strange phenomenon to reconcile with a supposed policy of “extermination.” A phenomenon still stranger in Bulgaria and in pre-war Romania or Denmark or Finland. A phenomenon stranger and stranger when one thinks of all of the associations throughout the world with, among their members, survivors of the “Holocaust” who, like Simon Wiesenthal himself, went from death camp to death camp without Hitler ever killing them.

The “Wannsee Protocol” (i.e. minutes), to which, for reasons that I do not have time to give here, I accord no value, passes for authentic with the exterminationists. For this reason I shall point out to them that those minutes mention 865,000 Jews for France in 1941, whence one would have to conclude that not even one tenth of the Jews of France were deported.

9. On page 214, in footnote 28, Vidal-Naquet writes:

Faurisson presents (Vérité…, p. 98, 115) the findings of the Comité d’histoire de la (Deuxième) Guerre mondiale on the total number of non-racial deportees as being inaccessible. They will be found quite simply in J.-P. Azéma, De Munich à la Liberation, 1979, p. 189: 63,000 deportees, of whom 41,000 were members of the resistance, an estimate obviously lower than those previously authoritative.

Response: I have never limited my criticism to the fact that this committee was hiding “the total number of non-racial deportees.” I have always rebuked it for hiding the total number of true deportees, racial or non-racial. And one will note that my criticism remains as valid today as yesterday, and that neither that committee, nor Azéma, nor Vidal-Naquet dares to disclose the number of racial deportees. Therefore I am going to do it in their stead: THE NUMBER THAT HAS BEEN KEPT HIDDEN FROM US FOR NINE YEARS IS… 28,162. (For the non-racial deportees, it is exactly 63,085). Obviously, that figure of 28,162 Jews is terribly embarrassing. It was obtained after an investigation lasting twenty years. How to reconcile it with Klarsfeld’s figure: some 76,000? Here is a good subject for our exterminationists to reflect on. Must one imagine that the committee worked scientifically and that it gave the status of Jew only to those for whom that status had meant actual deportation? Must one think that Klarsfeld for his part counted as Jews all the Jews, whether they had been deported because of that status or any other: resistance, sabotage, spying, black market, common offence? I have no idea. I put the question and I would indeed like some clarification. Let our people put their violins in unison!

Vidal-Naquet talks about 63,000 deportees, including 41,000 résistants, as an “estimate obviously lower than those previously authoritative“; I find him a little bit elusive. He ought to be more precise and recall for us that at the main Nuremberg trial the number of deportees from France was officially 250,000 (IMT, Vol. VI, p. 325), which, one may note in passing, gives us an idea of the seriousness of that tribunal calling itself “military” and “international” when it was but a judicial masquerade, was not military (with the exception of the… Soviet judge) and was not international but inter-Allied, and that in it the victors cynically judged the vanquished on the basis of a charter that contained such judicial abominations as its Articles 19 and 21.

10. On pages 214 and 215 Vidal-Naquet writes “It is quite simply a brazen lie to compare the Nazi camps with the camps created by a perfectly scandalous decision of the Roosevelt administration to house Americans of Japanese origin (Faurisson, in Vérité…, p. 189)”.

Response: In fact, I wrote “I call ‘genocide’ the act of killing people because of their race. Hitler no more committed ‘genocide’ than did Napoleon, Stalin, Churchill or Mao. Roosevelt interned American citizens of Japanese race in concentration camps. That was not a ‘genocide’ either.” Let people reread my sentences well. Where is there a “comparison” of the German camps and the American camps? Where is the “brazen lie” on my part? If I had had to compare them, it would have been to say that at all events it was probably better to live in a concentration camp run by an opulent nation like the United States in 1941 than one run by a nation like Germany where shortages of all sorts were rife. Azéma, already quoted, writes in footnote 2 on page 189, in regard to mortality in the German camps: “The final weeks, when the epidemics raged endemically, and the last transfers were particularly deadly.”

That said, concentration camps are a modern invention that we owe not to the British in their war against the Boers but to the Americans during their War of Secession, and I think that the horrors of Andersonville[1] must have been indeed as bad as the horrors of the English, German, Russian or French camps. Let us recall modestly into what state, right after the war, we put many of our German prisoners of war and, for those with a short memory, let us recall that the Americans demanded the return from France of the Germans whom they had lent to us, and that the transfer operation had taken the name “Operation Skinny” (an operation involving those with nothing more than the skin on their bones).

11. On page 215 Vidal-Naquet writes: “… it is the responsibility of historians to take the historical facts out of the hands of the ideologues who exploit them. In the case of the genocide of the Jews, it is obvious that one of the Jewish ideologies, Zionism, engages in an exploitation of the great massacre that is sometimes scandalous.”

Response: Fine indeed. But when I say that, people cry anti-Semitism and have me heavily sanctioned by the French judicial apparatus: 360 million old French francs in fines, a three-month prison sentence (suspended) – and not one colleague to express his astonishment at these rulings against a professor with only his salary. For the only parties that I accuse in this enormous lie of the “gas chambers” and the “genocide” are international Zionism and the State of Israel. Quite precisely, I accuse them of being its main beneficiaries.

12. Vidal-Naquet speaks, on page 216, of the “demonstration made by Faurisson that the Diary of Anne Frank is, if not a ‘literary fraud’, at least a tampered document”. Then comes the following comment: “On the scale of the history of the Hitlerite genocide, that modification is a matter of a comma.”

Response: Here is something disturbing! The same Faurisson who sees himself called an inveterate liar and a complete forger on nearly every page would suddenly have the analytical qualities needed to detect a tampered document where millions of readers, in 54 languages, saw, at the least, a work of poignant authenticity and which by itself had done more for the good exterminationist cause than the six million dead. Is Faurisson a dual being? Does he suddenly split from one into two? If so, we must be shown how. For many readers are going to think that, after all, Faurisson has applied one single method (textual, pragmatic, level with the facts) to distinguish the true and the false in all matters.

13. On page 216, in footnote 30, Vidal-Naquet writes: “You will find in her article [that of Nadine Fresco, “Les Redresseurs de morts”, op. cit.] an excellent analysis of the methods of revisionist history.”

Response: In that long article, verbose and, as has been said, “of a laughing tone,” I have found no trace of any analysis whatever. I was named 150 times. I believed I had the right to reply. I therefore sent the journal a right of reply text. Les Temps Modernes let me know that there was no question of publishing it because I denied the existence of the “gas chambers” (oral reply).[2]

14. On page 220 Vidal-Naquet rebukes the American revisionist Dr Austin App for having written: “The Third Reich wanted the emigration of the Jews, not their liquidation. If it had wanted to liquidate them there would not be 500,000 survivors of the concentration camps in Israel [an imaginary figure, says Vidal-Naquet] receiving German indemnities for imaginary persecutions.“

Response: In volume 14 of the Encyclopaedia Judaica, in the article on “Reparations, German”, it is stated that on March 12, 1951, Moshe Sharett, in support of the demand for financial reparations from Germany, pointed out the necessity of absorbing 500,000 victims of Nazism into the land of Israel. Twenty-seven years later, in Le Monde of November 3, 1978, page 10, there appeared this: “’A large part of the Israeli people has escaped from holocausts and is a living witness to the genocide committed by the Nazi beast,’ states a communiqué of the Israeli embassy in Paris.” Thirty-five years after the war, in the Bulletin quotidien de l’Agence Télégraphique Juive of December 9, 1980, under the title “Le Parti des survivants”, one could read: “The survivors of the Holocaust number between 200,000 and 500,000 in Israel. They are aged from 45 to 75, specifies Tuvia Friedmann”.

15. On page 221 Vidal-Naquet reproaches the revisionists for requesting proof from those who state that the “gas chambers” and the “genocide” really existed. He does so in the following terms: “For here we are: obliged, ultimately, to prove what happened to us. We who, since 1945, have known, here we are required to be demonstrative, eloquent, to use the weapons of rhetoric, to enter into the world of what the Greeks called Peitho, Persuasion, of which they had made a goddess who is not ours. Do people really realise what this means?“

Response: It seems normal to me for a historian to prove what he alleges and it seems to me abnormal to consider oneself dispensed from supplying one’s proof. Let’s note, by the way, a confession that is quite considerable: up to the present the exterminationists proved nothing for… they knew! Such is indeed the reproach that we’ve always made against them: on the question of the “gas chambers” and the “genocide”, the exterminationists have contented themselves with a sort of intuitive, inherent, metaphysical, religious, intangible knowledge. They were sure that that must be enough. Well, no: it’s no longer enough, precisely.

16. On page 222, in note 41, Vidal-Naquet writes that Faurisson and Thion have dared to maintain that no expert examination of a gas chamber has ever been made. He says: “That is false; I have before me the translation of an expert examination carried out at Cracow in June 1945 on the ventilation openings of the Birkenau gas chamber (crematorium no. 2), on 25 kilograms of women’s hair and on the metallic objects found in that hair. This examination which, as Georges Wellers tells me, uses classic methods, reveals compounds of hydrogen cyanide in that material”.

Response: I am familiar with the expert examinations ordered by examining magistrate Jan Sehn and carried out by the laboratory in Copernicus Street in Cracow. THEY ARE, PRECISELY, NOT EXAMINATIONS ESTABLISHING THAT THAT BUILDING WAS A HOMICIDAL GAS CHAMBER. And I ask why that elementary examination (which, besides, is still possible today) was not made. What Vidal-Naquet calls or christens “gas chamber” of crematorium no. 2 was a Leichenkeller, that is, an ordinary morgue, sitting half under ground level to protect it from the summer heat, in a cul-de-sac, 30 metres by 7 metres in size, with support pillars in the middle. I know the ventilation system quite precisely. A morgue has to be disinfected. For this they used Zyklon-B, an insecticide invented in 1922 and still used today the world over. Zyklon-B is an absorbent of hydrocyanic acid on an inert, porous base – diatomaceous earth – that slowly releases gaseous hydrocyanic acid on contact with the air. It is therefore normal that an expert examination should turn up remains of that acid. As regards the hair, I shall recall that, during the war, hair was gathered from all the hairdressers’ salons of Europe; in factories or in the camps it was used to make carpets, fluff material, shoe heels, etc. Besides, the camps were overloaded with these materials for recycling, explained today to tourists and onlookers as all coming from the victims. I personally have a series of documents that prove that a portion of the hair displayed in the National Museum at Auschwitz came in fact from a carpet and fluff material factory at Kietrz, about 90 kilometres from Auschwitz as the crow flies. Traces of hydrocyanic acid were found in them, which, there again, was quite normal.

I renew here my persistent request that finally, 37 years after the end of the war, there be ordered an expert examination on every enclosure (either in its original condition or in ruins) that the authorities presume to christen a homicidal gas chamber. Let the first one be done at Struthof after, if necessary, a rereading of the Simonin/Fourcade/Piedelièvre reports and, especially, the impossible to find report of Professor René Fabre, toxicologist.

17. On page 223 Vidal-Naquet writes: “Faurisson contents himself with scoffing… at ‘miraculously rediscovered manuscripts’, the inauthenticity of which he does not even attempt to demonstrate”.

Response: In my Mémoire en défense, which appeared after this book by Vidal-Naquet, I prove the inauthenticity of those manuscripts. I do so on pages 232 to 236, in the chapter entitled “The Trickeries of the LICA and all the Others”. I advise Vidal-Naquet to read, further, the special issue of the Hefte von Auschwitz, Sonderheft 1, Handschriften von Mitgliedern des Sonderkommandos (Manuscripts of Members of the Special Commandos) (Auschwitz State Museum Publishing Company, 1972). In the preface, on pages 5 and 17, he will see, not without surprise, the extent to which the Poles rebuked the first publisher of those manuscripts for his transformations and manipulations. That publisher is none other than the illustrious Professor Bernard Mark, director of the Institute of Jewish History in Warsaw, who was denounced as a forger by the Polish Jew Michel Borwicz in the Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale, January 1962, page 93.

18. On the same page 223 Vidal-Naquet faults me for including The Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto, by Emmanuel Ringelblum, among the “fake, apocryphal, or suspect” works.

Response: Let this matter be decided rather by the book’s presentation alone! I have before me: Emmanuel Ringelblum, Chronique du Ghetto de Varsovie (Léon Poliakov’s French version after the adaptation by Jacob Sloan, Robert Laffont, Paris 1978, 375 p.). The translator’s note on page 7 begins as follows:

At the request of the editor, I have followed for this version of the Chronicle of Emmanuel Ringelblum the selection established by Mr Jacob Sloan, published in the United States in 1958 by McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. – I have nevertheless taken care to collate this text with the original edition in Yiddish, published in 1952 by the Institute of Jewish History in Warsaw […] The Warsaw edition presents gaps explained especially by the place and date of publication. Unfortunately, neither Mr J. Sloan nor myself have been able to see the original text of the manuscript preserved in Warsaw [my emphasis].

Must I recall here – last but not least – that the Warsaw institute’s director, whose name Léon Poliakov does not give, is the forger Bernard Mark?

19. On page 224 Vidal-Naquet returns to a quotation from Himmler and talks about “coded language,” then quotes Goebbels who, in his Diary, on May 13, 1943, writes: “The modern peoples have, therefore, no other solution than to exterminate the Jews”.

Response: As regards Himmler, I refer back to my paragraph 2, above. As regards what is “decoded”, I would say, “Enough decoding!” As regards Gœbbels, I would say that warlike phraseology is always the same; it is always a question of exterminating the enemy to the last; see the words of our “Marseillaise”; see also the examples quoted by Dr Wilhelm Stäglich in Der Auschwitz Mythos, pages 82-85 (Churchill, statements by Vansittart, Ilya Ehrenburg and Zionist officials, etc.); even a Jewish intellectual like Julien Benda, who wished to pass for a rationalist, wrote as follows on page 153 of Un Régulier dans le siècle (Gallimard, Paris 1938; 254 p., p. 153):

For my part, I maintain that by their morality the modern Germans are collectively one of the plagues of the world, and if I had only to press a button to exterminate them entirely, I would do it on the spot, even if I had to lament the few just people who would die in the process.

That said, Goebbels repeats several times in his Diary, and still on May 7, 1943, “The Jews must be driven out of Europe.” At that date they have not even been driven out of Berlin and, at the Liberation, in May 1945, the surprising discovery was made that there still existed in Berlin at least one Jewish day-nursery and a Jewish old people’s home. As for Europe, it still counted millions of Jewish inhabitants.

20. On page 224 Vidal-Naquet writes that it is “a bit surprising […] that no SS leader denied the existence of the gas chambers”.

Response: That is quite simply false. In the transcripts of the trials one may observe quite often the obstinacy of those who had been in charge of the camps in not wanting to admit “the obvious”. See, in my Mémoire en défense, on page 45, what Germaine Tillion dares to write about the commandant of Ravensbrück:

Commandant Suhren was naturally interrogated several times on the subject of the gas chamber. He began by denying its existence, then admitted it, but said it was outside of his scope of command and maintained that position despite the obviousness of the contrary. “I estimate”, he said (during the interrogation of December 8, 1949), “the number of women gassed at Ravensbrück at about 1,500.”

HOWEVER, IT IS NOW ACKNOWLEDGED THAT THERE WAS NEVER ANY GAS CHAMBER IN THAT CAMP, where, furthermore, that astonishing “gas chamber” has never been located!! The same diabolical obstinacy on the part of Josef Kramer regarding Auschwitz. He said in his first deposition that he had heard the allegations of former Auschwitz prisoners according to whom there was a gas chamber there and that that was entirely false. But in a later deposition, he said that there had been ONE gas chamber but that it was under the authority of Höss (Trial of Josef Kramer and Forty-four Others, edited by Raymond Phillips, William Hodge and Co., London 1949, p. 731 and 738). With the same Josef Kramer, the French military justice system outdid itself for the alleged homicidal “gas chamber” of Struthof. It extorted from him two totally contradictory confessions about the conduct of the gassing operation (Celle, July 26, 1945, and Luneburg, December 6, 1945). If Richard Baer, in the course of an interrogation in 1962 or 1963, had acknowledged the existence of “gas chambers” at Auschwitz, where he had been commandant, there is no doubt that the prosecution at the Frankfurt trial would have instanced it with regard to his 22 accomplices, who were so recalcitrant or so vague on the subject.

I repeat here that it is impossible to flout a taboo. One comes to terms with it, as all the German lawyers have done by advising their clients to deny nothing about the matter, let the prosecution say what it wishes and content themselves with stating that, as regards themselves, they had nothing to do with so foul an affair. Thus in the witchcraft trials, the witch did not go so far as to say “The best proof that I did not meet the devil is that the devil doesn’t exist.” She would have appeared diabolical for that. She hedged. The devil was doubtless indeed there. There was a racket in the distance. “But that was on the top of the hill and I was at the bottom of that hill.”

Not one of the defendants at the big Nuremberg Tribunal admitted to having had knowledge of the “gas chambers” and the “genocide”, not even Frank, the former governor of Poland, who was lost in the worst Christian repentance, not even Speer, the most “collaborative” with his judges and with his conquerors. Speer was later to publish, at the request of his Jewish friends, a text in which he said he held himself responsible… for his blindness! He, the minister of armaments, having, all things considered, control over the concentration camps’ activity, had not SEEN that formidable slaughterhouses for humans, requiring thousands of tons of coal for the incineration of the bodies of victims of the genocide, were operating, so it seems, day and night! Speer was rewarded for his goodwill. His books sold in the millions, with the detail that “after taxes, he went fifty-fifty with the Jewish organisations, notably the French ones”. (Remarks made on French television during the presentation of his first book.)

In Volume 42 of the transcripts and documents of the IMT, the reader discovers document PS-862. It informs us that, of the 26,674 former political leaders interrogated, not one had heard talk of the “extermination” of the Jews or of the “extermination camps” before the surrender in May 1945. Is it imaginable that the strength of the taboo is such that 36 years after the war a French professor who dares to deny the “genocide” and the “gas chambers” should see himself sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, suspended, and ordered to pay 360 million old francs in fines and publication costs? And then, in order to deny that those horrors existed, it also takes years of examining the question from the technical point of view. Ordinary mortals (the Germans and their conquerors, scientists and laymen alike) have a tendency to think, when someone talks to them about homicidal “gassing”, that it’s the simplest of operations. That being the case, try to claim that this shower, that concrete building wasn’t used for “gassing”! You think: “How would I go about demonstrating that that commonplace operation didn’t take place in the building shown to me?” And you keep quiet. And your silence passes for an approval. It’s said about you, triumphantly: “You see! He hasn’t denied it!”

21. On page 225 Vidal-Naquet writes that my technical considerations on the American gas chambers, in which one sees how difficult it is to kill a single human being, do not prove at all that it is impossible to carry out mass gassings. He adds that “the operation of gassing, like that of feeding oneself, can be accomplished in immensely different conditions“.

Response: I understand nothing of that reasoning, of those abstractions or those allusions. It seems to me that, if it is dangerous to gas one man, it must be still more dangerous to gas masses of men. I must reveal here that the LICRA [International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism], on February 4, 1981, consulted the leading toxicologist in France, Mr Louis Truffert, in a perfectly captious and abstract letter to ask him whether it was so difficult as all that to air out a room gassed with Zyklon. Mr Truffert then made a reply that went rather in the direction hoped for by the LICRA. Unfortunately for the LICRA, I happened to know Mr Truffert, with whom I had never yet talked about my argument on the non-existence of the Hitlerite “gas chambers,” but with whom I had had a very long discussion on hydrocyanic acid. In the company of my publisher, Pierre Guillaume, I went to see Mr Truffert again, but this time I presented him with the plans for Auschwitz, and in particular the “re-enactment” (sic) of a “gassing” found in room 4 of the Auschwitz Museum. Please believe me that Mr Truffert’s reaction was instantaneous. He immediately exclaimed at the impossibility of a homicidal gassing operation in such conditions. And it is this that he agreed to confirm for us in a letter of April 3, 1981, of which the LICRA was to receive a copy. Here is the passage directly concerning the question:

Nevertheless, the observation that I made [in my reply to the LICRA], concerning the possibility of entering, without a gas mask, a room containing bodies poisoned with hydrocyanic acid, concerns the case of a gas chamber at ground level, opening onto the fresh air and it is obvious that significant reservations must be made in the case of installations below ground level. Such a situation would require a very large ventilation apparatus and draconian precautions in order to avoid pollution liable to cause accidents.

Could Vidal-Naquet be more precise about how I have used an “arsenal” that is not technical but “pseudo-technical”? Is the consulting of six American penitentiary officials insufficient, and is Vidal-Naquet really able to make suggestions of a scientific order to the Americans for a formidable simplification of gassing procedures?

22. On page 225 Vidal-Naquet faults me for attributing the meaning “gassing” to “Vergasung” when I translate Dr Broszat’s Keine Vergasung in Dachau and as “carburation” when, in a document from January 1943, I encounter “Vergasungskeller,” a word that Raul Hilberg is careful not to cite.

Response: It is all a matter of context! Besides, “Vergasung” can have still other meanings. Applied to an account of a gas warfare battle in 1918, it can be translated as “gassing.” It can also be a question of non-homicidal gassing. For example, in a radio message of July 22, 1942 addressed to the Auschwitz camp, signed by General Glücks, we read: “I hereby grant authorisation for one five-ton truck to make the return journey Auschwitz to Dessau [the place where Zyklon-B was distributed] in order to pick up gas intended for the gassing of the camp, to combat the epidemic that has broken out.” The German text has “Gas für Vergasung“: gas intended for gassing. Finally, at Dachau, the building that houses the disinfestation gas chambers is called the “Vergasungsgebäude“.

23. On page 225 Vidal-Naquet rebukes me for not devoting a line either to the Einsatzgruppen or to Babi-Yar.

Response: They were not the subject. Similar police operations and similar places of execution also existed among the enemy who had to be fought by the German on the Russian front. Euthanasia or medical experiments are likewise foreign to the subject. On these two last points, I have the impression that quite a lot of things have been made up. I know researchers who are looking into all these secondary topics. Let’s await their conclusions.

24. On page 225 Vidal-Naquet reproaches me for saying that numerous gypsy children were born at Auschwitz without saying what became of them. He adds that they were exterminated.

Response: I cite my sources: Les Cahiers d’Auschwitz (The Auschwitz Notebooks). If those children had been the victims of a Herodian slaughter at birth, Les Cahiers d’Auschwitz would not have failed to inform us about each one of them. I suppose that some of those children died and that some of them survived and were to be found in the long cohort of healthy children whom the Soviets filmed at the time of the camp’s liberation. I recall that bands of Gypsies continued to wend their way through Europe at war (see Céline’s Nord). Vidal-Naquet states that those children were exterminated. Where does he get that information?

25. On page 226 Vidal-Naquet writes: “[Faurisson] maintains that in France it was the résistants who made the Gypsies disappear.”

Response: In reality, I write on page 192 of Vérité…: “I recall that in France even the résistants could look unfavourably upon the Gypsies and suspect them of espionage, informing and black-marketeering”. And one of my footnotes refers to the following text: “I have personally made a detailed inquiry about the summary executions carried out by the résistants in a small region of France: I was surprised to note that the Gypsy communities had paid a heavy toll in dead, not by the doing of the Germans, but by the doing of the résistants.”

But where does Vidal-Naquet get the idea that the Gypsies have disappeared?

26. In a footnote on page 227 Vidal-Naquet is pleased to recall a sentence that I have repeated for years and that I shall repeat here once more: “I have searched, but in vain, for a single former deportee capable of proving to me that he had really seen, with his own eyes, a gas chamber.”

Response: Vidal-Naquet proposes no name to me; neither that of Martin Gray nor that of Filip Müller (with whom I have asked the television personality Bernard Volker to put me face to face), nor Maurice Benroubi (discovered by L’Express), nor Yehuda Bauer or a friend of his (to whom I said I was ready to go on Israeli television), nor Elie Wiesel, Samuel Pisar, Simone Veil, Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier, Louise Alcan, Fania Fénelon, or Dr Bendel. In two years of research, the LICRA and its consorts were able to find for me only Mr Alter Fajnzylberg, known as Jankowski: they obtained from him a very short deposition, submitted to Mr Attal, a notary in Paris. I was delighted at the prospect of meeting this person in court. In his place came an orator with a quavering voice.

27. On page 228 Vidal-Naquet cites “documents on Auschwitz and on Treblinka (spelt Trembinki) that served as the basis for an American publication of November 1944 from the ‘Executive Office of the War Refugee Board.’” He states: “There is nothing there that does not tally, as concerns the essential matters, with either the documents of the members of the Sonderkommandos or the testimonies of the SS leaders.”

Response: I have not noted that in this document from the War Refugee Board it was a question of Treblinka or of Trembinki. It is above all a question of Auschwitz and, a bit, of Majdanek (where no mention is made of the existence of “gas chambers”). It is curious that this document was not used in the big Nuremberg trial, where a page of fanciful statistics was simply reproduced from it (Document L422).

As regards Auschwitz, this document, in fact, tallies so little with the physical realities that it sufficed for Wilhelm Stäglich, in his aforementioned work, to juxtapose two photographs: on the one hand, the plan from photographic plate no. 12 (= reality), and, on the other hand, the plan from photographic plate no. 13 (= WRB fiction).

The WRB’s fabrication is obvious. I shall recall that it is in this document, published by Roosevelt’s entourage and, among others, by the famous Morgenthau, that Katyn is ascribed to the Germans.

As for the “gassings”, they were carried out, according to the anonymous Polish officer, by throwing “hydrogen cyanide bombs” (p. 13 of the English text)! This WRB report has a whole dubious and interesting history, very well revealed by Butz, on the one hand, and by Stäglich on the other: it is enough to look up, in their books’ indexes, the names of the presumed authors of the first report: Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler. There is also an interesting study by Stäglich in the journal Deutschland in Geschichte und Gegenwart (Grabert Verlag, Tübingen 1981, 1, p. 9-13. I shall point out that the alleged plan of the premises is found on page 15 of the American version and that it does not appear in the French version (Les Camps d’extermination allemands d’Auschwitz et Birkenau, Office Français d’Edition, 2nd quarter of 1945, 55 p.).

28. On page 228 Vidal-Naquet dares to appeal to the “confessions” of Kurt Gerstein, which he says have been confirmed by Professor Pfannenstiel himself, who is said to have visited Rassinier in Paris to speak with him about them.

Response: In the different and gravely contradictory versions of the “confessions” of Gerstein, the incongruities, the silliness, the nonsensical features (see above, the 28 to 32 people per square metre) are so numerous that one fails to understand how the Gerstein argument can still be used. Léon Poliakov has inundated these different versions with what Vidal-Naquet himself has been obliged to acknowledge as “culpable errors.” There’s a fine euphemism!

A doctoral thesis is currently being prepared that will expose the Gerstein “confessions” and what Léon Poliakov has done with them.[3] In her own 1968 thesis Olga Wormser-Migot had the caution to write (p. 426): “For our part we have difficulty in accepting the complete authenticity of the confession of Kurt Gerstein or the veracity of all its elements.” As for what Dr Pfannenstiel has stated several times in the German courts, here it is: 1) he speaks of Gerstein almost as a liar on several points; 2) he is extremely vague about the “gassing” that he is supposed to have witnessed one day by Gerstein’s side: a Diesel “gassing”, which in itself is a rather curious way of gassing given the slight emission of deadly carbon monoxide from a system above all rich in carbon dioxide.

Is Pfannenstiel supposed to have gone to see Rassinier in Paris? That is very often said, but I know nothing about it since the visitor refused to give his name. It could be. How many times has a Nazi, bound by his “confessions” and rewarded for them, served the good exterminationist cause on command in dealings with a hardened revisionist or Nazi? When Dr Johann-Paul Kremer returned from his long detention in Poland and wanted to begin talking again, the German justice system had him understand that it was in his interest to keep quiet. He kept quiet. And he was re-employed as a witness for the prosecution at the Frankfurt trial (1963-65) but always with that extraordinary discretion of the German judges on the actual “gassing” operations. I’ve come to know a short correspondence between Rassinier and Pfannenstiel. I propose to publish it one day to show how Pfannenstiel sought to evade Rassinier’s simple technical questions.

And then on Belzec, one ought to be clear. Gerstein said that there was “gassing” there, but there exist other arguments just as believable or unbelievable and, as far as I can see, our court historians have not been able to eliminate them in favour of the Gerstein thesis. According to Jan Karski the Jews were being killed with quicklime. According to the New York Times (February 12, 1944, p. 6) the Jews were being electrocuted. According to Dr Stefan Szende there was quite a sophisticated way of proceeding: the same platform that electrocuted the Jews was raised out of the water; it was brought to red hot and the Jews were burned up. Today Karski is a professor at Georgetown University in Washington. In 1944 he published Story of a Secret State (Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston; Riverside Press, Cambridge, 391 p.). Here is what may be read on pages 349-351 of his book:

… I know that many people will not believe me, will not be able to believe me, will think I exaggerate or invent. But I saw it and it is not exaggerated or invented. I have no other proofs, no photographs. All I can say is that I saw it and that it is the truth. The floors of the car containing the Jews had been covered with a thick, white powder. It was quicklime. Quicklime is simply unslaked lime or calcium oxide that has been dehydrated. Anyone who has seen cement being mixed knows what occurs when water is poured on lime. The mixture bubbles and steams as the powder combines with the water, generating a large amount of heat. Here the lime served a double purpose in the Nazi economy of brutality. The moist flesh coming in contact with the lime is rapidly dehydrated and burned. The occupants of the cars would be literally burned to death before long, the flesh eaten from their bones. Thus, the Jews would “die in agony,” fulfilling the promise Himmler had issued “in accord with the will of the Führer,” in Warsaw in 1942. Secondly, the lime would prevent decomposing bodies from spreading disease. It was efficient and inexpensive a perfectly chosen agent for their purposes. It took three hours to fill up the entire train by repetitions of this procedure. It was twilight when the forty-six (I counted them) cars were packed. From one end to the other the train, with its quivering cargo of flesh, seemed to throb, vibrate, rock, and jump as if bewitched. There would be a strangely uniform momentary lull and then, again, the train would begin to moan and sob, wail and howl. Inside the camp a few score dead bodies remained and a few in the final throes of death. German policemen walked around at leisure with smoking guns, pumping bullets into anything that by a moan or motion betrayed an excess of vitality. Soon not a single one was left alive. In the now quiet camp the only sounds were the inhuman screams that were echoes from the moving train. Then these, too, ceased. All that was now left was the stench of excrement and rotting straw and a queer, sickening, acidulous odour which, I thought, may have come from the quantities of blood that had been let, and with which the ground was stained. As I listened to the dwindling outcries from the train, I thought of the destination toward which it was speeding. My informants had minutely described the entire journey. The train would travel about eighty miles and finally come to a halt in an empty barren field. Then nothing at all would happen. The train would stand stock-still, patiently waiting while death penetrated into every corner of its interior. This would take from two to four days.

When quicklime, asphyxiation, and injuries had silenced every outcry, a group of men would appear. They would be young, strong Jews, assigned to the task of cleaning out these cars until their own turn to be in them would arrive. Under a strong guard they would unseal the cars and expel the heaps of decomposing bodies. The mounds of flesh that they piled up would then be burned and the remnants buried in a single huge hole. The cleaning, burning, and burial would consume one or two full days. The entire process of disposal would take, then, from three to six days. During this period the camp would have recruited new victims. The train would return and the whole cycle would be repeated from the beginning.

But let’s come to Dr Szende. The first edition of his book appeared in Sweden under the title Den Siste Juden från Polen (The Last Jew From Poland; Albert Bonniers Förlang, Stockholm 1944). The second edition appeared in Switzerland as Der letzte Jude aus Poland (Europe Verlag, Zurich 1945). The third edition appeared in Britain as The Promise Hitler Kept (Victor Gollancz, London). The fourth appeared in the United States with the same title (Roy Publishers, New York 1945). I reproduce here a short passage from page 161 of the American edition:

When trainloads of naked Jews arrived at Belzec, they were herded into a great hall capable of holding several thousand people. This hall had no windows and its flooring was of metal. Once the Jews were all inside, the floor of this hall sank like a lift into a great tank of water which lay below it until the Jews were up to their waists in water. Then a powerful electric current was sent into the metal flooring and within a few seconds all the Jews, thousands at a time, were dead. The metal flooring then rose again and the water drained away. The corpses of the slaughtered Jews were now heaped all over the floor. A different current was then switched on and the metal flooring rapidly became red hot, so that the corpses were incinerated as in a crematorium and only ash was left.

The floor was tipped up and the ashes slid out into prepared receptacles. The smoke of the process was carried away by great factory chimneys. That was the whole procedure. As soon as it was accomplished, it could start up again. New batches of Jews were constantly being driven into the tunnels. The individual trains brought between 3,000 and 5,000 Jews at a time, and there were days on which the Belzec line saw between twenty and thirty such trains arrive.

Modern industrial and engineering technique in Nazi hands triumphed over all difficulties. The problem of how to slaughter millions of people rapidly and effectively was solved.

The underground slaughter-house spread a terrible stench around the neighborhood, and sometimes whole districts were covered with the foul-smelling smoke from the burning human bodies.

This account, which Dr Stefan Szende is supposed to have obtained from one Adolf Folkman, is mad, but less mad and more coherent than the “confessions” of Kurt Gerstein, which, let it be said in passing, stand in serious contradiction with the “truth” about Treblinka as established at the big Nuremberg trial. At Treblinka, whatever Gerstein may say, the Jews were not gassed, but were… scalded (see, for the savoury details, document PS-3311).

Here again I ask Vidal-Naquet: To whom must we turn? And why to one rather than another?

29. On page 223 Vidal-Naquet writes that there are some more than doubtful “testimonies” in which an SS man, like Pery Broad for instance, seems to have adopted entirely the language of the victors. He adds that Pery Broad’s written statement on Auschwitz was drawn up for the English (the last three words are emphasised by Vidal-Naquet himself).

Response: I know of few fakes so patent as the written statement of Pery Broad. Vidal-Naquet seems in agreement with me in seeing a fake here, but he clearly draws no conclusion from the fact. This fake is ENGLISH and, at the same time, of a construction and a tone that are perfectly Stalinist, to the point of caricature. I say this to reply to the naive people who claim, against all evidence and inquiry, that no torturing was done in the Allied prisons and who add: “See how the confessions taken in the West and the confessions taken in the East concur.” I shall point out in passing that in the civil action brought against me by the LICRA and eight other associations, the Pery Broad statement was produced in evidence. What disarray they must have fallen into, reduced to submitting that kind of “proof of the gas chambers’ existence”!