The orthodox historians’ disputing of the Nuremberg judgment

In France, the Fabius-Gayssot Act of July 13, 1990 forbids the disputing of the existence “of crimes against humanity” as defined and punished, just after the war, by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg (1945-1946). This prohibition, which targets the revisionists, is all the more improper as the orthodox authors, for their part, have carried out considerable revisions and disputing in the field. For a brief look into the matter, here are but fifteen examples of their own revising and disputing. Each one of them is followed by a remark of mine.

1) In 1951 Léon Poliakov wrote on the subject of the “programme to exterminate the Jews of Europe”: “No document remains, perhaps none has ever existed” (Bréviaire de la haine, Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1974 [1951], p. 171; English version: Harvest of Hate, Holocaust Library, New York 1979, revised and expanded edition).

Remark: what right can there be to forbid the disputing of a history that “perhaps” rests on no documents?

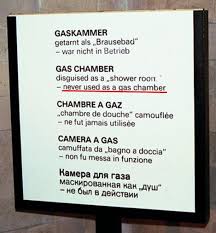

2) In 1960 Martin Broszat, member of the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich, wrote: “Neither at Dachau, nor at Bergen-Belsen, nor at Buchenwald were any Jews or other detainees gassed” (“Keine Vergasung in Dachau”, Die Zeit, August 19, 1960, p. 16). However, at the Nuremberg trial, a film showing the alleged Dachau gas chamber was projected and there are numerous testimonies of alleged homicidal gassings in the three aforementioned camps. Today, at Dachau, a sign indicates in five languages that the “gas chamber” was never used.

It is impossible to know on what criteria the decision was taken, in 1960, thus to revise the history of those camps and not to revise, on the precise point of the gas chamber, the history of the other camps.

Remark: what right can there be to forbid the disputing of such a fluctuating, arbitrary history?

3) In 1968 Olga Wormser-Migot, in her thesis on Le Système concentrationnaire nazi, 1933-1945, (Presses universitaires de France, Paris), gave an ample exposition of what she called “the problem of the gas chambers” (p. 541-544). She voiced her scepticism as to the worth of some well-known witnesses’ accounts attesting to the existence of gas chambers in camps such as Mauthausen or Ravensbrück. On Auschwitz-I she was certain: that camp where, still today, tourists visit an alleged gas chamber “had no gas chamber”.

Remark: in light of the fact that the testimonies about other camps are no different from the testimonies about these three camps, one may well ask: what right can there be to have forbidden, since 1990, a disputing that was still allowed in 1968?

4) In 1979 thirty-four French historians signed a lengthy declaration in reply to my technical arguments aiming to demonstrate that the allegation of the existence and functioning of the Nazi gas chambers ran up against certain fundamental material impossibilities (notably, the impossibility for a group of men to enter, “while smoking and eating”, a room that was flooded with hydrogen cyanide and to touch, handle and drag out, using all their strength, thousands of bodies suffused with that poison). Drafted by Léon Poliakov and Pierre Vidal-Naquet, that declaration concluded: “One must not ask oneself how, technically, such a mass murder was possible. It was technically possible, since it happened.” (Le Monde, February 21, 1979, p. 23).

Remark: if thirty-four historians have found themselves unable to explain how a crime of this dimension was perpetrated, why should anyone not have the right to dispute the very reality of that crime?

5) In 1982 Raul Hilberg, going back altogether on his 1961 argument, stated that the process of “destruction of the European Jews” had, after all, gone on without a plan, without any organisation, centralisation, project or budget, but thanks to “an incredible meeting of minds, a consensus-mind reading by a far-flung bureaucracy” (Newsday, Long Island, New York, February 23, 1983, p. II/3). He would confirm this explanation under oath at the first Zündel trial in Toronto on January 16, 1985 (verbatim transcript, p. 848); he would confirm it anew but with other words in the profoundly revised version of his work The Destruction of the European Jews, Holmes & Meier, New York 1985, p. 53, 55, 62).

Remark: what right can there be to forbid the disputing of what the Number One historian of the Jewish genocide himself deems “unbelievable”? Must the unbelievable be believed? Must one believe in mind reading, particularly within a vast bureaucratic structure and, still more particularly, within the bureaucracy of the Third Reich? How does the process described by this prestigious historian differ from the workings of the Holy Spirit?

6) Also in 1982, an association was founded in Paris for “the study of murders by gassing under the National Socialist regime” (the “ASSAG”), “with a view to seeking and verifying evidence of the use of poison gasses in Europe by the officials of the National Socialist regime to kill persons of various nationalities, to contributing to the publication of this evidence, to making, to that purpose, all useful contacts on the national and international level”. Article 2 of the association’s charter stipulates: “The Association shall last as long as shall be necessary to attain the objectives set forth in Article 1.” However, this association, founded on April 21, 1982 by fourteen persons, amongst whom Germaine Tillion, Georges Wellers, Geneviève Anthonioz née de Gaulle, barrister Bernard Jouanneau and Pierre Vidal-Naquet, has, in nearly a quarter of a century, never published anything and, to this day in 2005, remains in existence. In the event that it be said, wrongly, that the group has produced a book entitled Chambres à gaz, secret d’État (Gas chambers, State secret), it will be fitting to recall that the book in question is in fact the French translation of a work first published in German by Eugen Kogon, Hermann Langbein and Adalbert Rückerl and in which there featured a few contributions by a few members of the “ASSAG” (Éditions de Minuit, Paris 1984; English translation published as Nazi Mass Murder: a documentary history of the use of poison gas, Yale University Press, New Haven 1994). The title alone gives an idea of the contents: instead of proof, supported by photographs of gas chambers, drawings, sketches, forensic reports on the crime weapon, the reader finds only speculations based on what is called “evidence” (éléments de preuve, “elements of proof”, not proof), and this because, we are told, those gas chambers had constituted the biggest possible secret, a “State secret”.

Remark: what right can there be to forbid the disputing of evidence (let alone proof) brought forth by an association which, as shown by the very fact of its existence still today in 2005, has not yet attained the objective for which it was founded, nearly a quarter of a century ago?

7) In Paris on April 26, 1983, the long-running lawsuit against me for “personal injury through falsification of history”, begun, notably by Jewish organisations, in 1979, came to an end. The first chamber of the Paris court of appeal, civil division section A, presided by judge Grégoire, held that there could be found in the my writings on the gas chambers no trace of nonchalance, no trace of negligence, no trace of having deliberately overlooked anything, nor any trace of a lie and that, as a consequence, “the appraisal of the value of the findings [on the gas chambers] defended by Mr Faurisson is a matter, therefore, solely for experts, historians and the public.”

Remark: how can judges, in good conscience, punish those who in their turn today carry on my questioning on “the problem of the gas chambers” (an expression used by the court of appeal in 1983)?

8) Still in 1983 Simone Veil declared on the subject of the gas chambers: “In the course of a case brought against Faurisson for having denied the existence of the gas chambers, those who bring the case are compelled to provide formal proof of the gas chambers’ reality. However, everyone knows that the Nazis destroyed those gas chambers and systematically did away with all the witnesses” (France-Soir Magazine, May 7, 1983, p. 47).

Remark: if neither the crime weapon nor any testimonies are to be found, have people not the right to dispute the reality of this crime? What must be said of the places presented to millions of deceived visitors as being gas chambers? What is one to think of the individuals who present themselves as witnesses or miraculous survivors of the gas chambers?

9) In 1986 Michel de Boüard, himself deported during the war as a résistant, professor of history and Dean of letters at the University of Caen, member of the Institut de France and former head of the Commission d’histoire de la déportation within the official Comité d’histoire de la deuxième guerre mondiale, stated that, all told, “the dossier is rotten”. He specified that the dossier of the history of the German concentration camp system was “rotten”, in his own words, because of “a huge amount of made-up stories, inexactitudes stubbornly repeated – particularly where numbers are concerned –, amalgamations and generalisations”. Alluding to the revisionists’ studies, he added that there were “on the other side, very carefully done critical studies demonstrating the inanity of those exaggerations” (Ouest France of August 2nd and 3rd, 1986, p. 6).

Remark: if a dossier is “rotten”, has one not the right and even the duty to dispute it?

10) In 1988 Arno Mayer wrote on the subject of the Nazi gas chambers: “Sources for the study of the gas chambers are at once rare and unreliable” (The “Final Solution” in History, Pantheon Books, New York p. 362).

Remark: what right can there be to forbid the disputing of historical sources of such rarity? Must the historian trust what is admittedly unreliable?

11) In 1989 Philippe Burrin, positing as a principle, with no demonstration, the reality of the gas chambers and the genocide, attempted to determine at what date and by whom the decision to exterminate physically the Jews of Europe had been taken. He did not succeed any more than all his “intentionalist” or “functionalist” colleagues (Hitler et les juifs / Genèse d’un génocide, Seuil, Paris; English version: Hitler and the Jews: the Genesis of the Holocaust, Edward Arnold, London 1994). He noted what he called the absence of traces and “the stubborn erasure of the trace of anyone’s passing through” (p. 9). He bemoaned “the large gaps in the documentation. There subsists no document bearing an extermination order signed by Hitler. In all likelihood, the orders were given verbally. […] here the traces are not only few and far between, but difficult to interpret” (p. 13).

Remark: if a historian can produce no documents to such effect, signed by Hitler or anyone else, but only what he calls “traces”, few in number at that and sparse and difficult to interpret, what right can there be to forbid the disputing of the general argument that the historian persists in defending?

12) In 1992 Yehuda Bauer, professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, stated at an international conference on the genocide of the Jews held in London: “The public still repeats, time after time, the silly story that at Wannsee the extermination of the Jews was arrived at” (Jewish Telegraphic Agency release published as “Wannsee’s importance rejected”, Canadian Jewish News, January 30, 1992, p. 8)

Remark: apart from the fact that the “minutes” of the Berlin-Wannsee meeting of January 20, 1942 prove that the Germans envisaged a “territorial final solution [eine territoriale Endlösung (doc. NG-2586, p. 4)] of the Jewish question” leading in the end to a “Jewish renewal” in a territory to be determined, does not Yehuda Bauer’s quite belated declaration confirm that this major point of the official version of Jewish genocide still needs questioning? The extermination of the Jews was decided neither at Wannsee nor anywhere else; the expression “extermination camps” is but an invention of American war propaganda and there are examples proving that, during the war, the killing of a single Jewish man or woman exposed the perpetrator, whether soldier or civilian, member of the SS or not, to German military justice proceedings and the possibility of being shot by firing squad (in sixty years, never has a single orthodox historian provided an explanation for such facts).

13) In 1995 French historian Eric Conan, co-author with Henry Rousso of Vichy, un passé qui ne passe pas (Gallimard, Paris 2001 [1994, 1996]; English version: Vichy: an ever-present past, University Press of New England, Hanover [New Hampshire] and London 1998), wrote that in the late 1970s I had been right after all to certify that the gas chamber thus far visited by millions of tourists at Auschwitz (500,000 each year) was completely fake. According to E. Conan “Everything in it is false […]. In the late 1970s, Robert Faurisson exploited these falsifications all the better as the [Auschwitz] museum administration balked at acknowledging them”. Conan went on: “[Some people], like Théo Klein [former president of the CRIF, the ‘representative council of Jewish organisations of France’], prefer that it be left in its present state, while explaining the misrepresentation to the public: ‘History is what it is; it suffices to tell it, even when it’s not simple, rather than to add artifice to artifice’”. Conan then related a staggering remark by Krystyna Oleksy, deputy director of the Auschwitz National Museum, who, for her part, could not bring herself to explain the misrepresentation to the public: “For the time being, [the room in question] is to be left ‘as is’, with nothing specified to the visitor. It’s too complicated. We’ll see later on” (Auschwitz: la mémoire du mal [“Auschwitz: the remembrance of evil”], L’Express, January 19-25, 1995, p. 68).

Remark: do these words of a Polish official not mean: “We have lied, we are lying and, until further notice, we shall continue to lie”? In any inquiry on the subject of the gas chambers, is it not appropriate to start by calling into doubt their existence and thus to dispute what one is shown or told about them by reputedly reliable authorities? It is noteworthy that in 2001 the fallacious character of this Potemkin village gas chamber was finally to be acknowledged in a French booklet accompanying two CD-Roms entitled Le Négationnisme; written by Jean-Marc Turine and Valérie Igounet, it was prefaced by Simone Veil (Radio France-INA, Frémeaux & Associés, Vincennes 2001, p. 27-28).

14) In 1996 the leftwing French historian Jacques Baynac, a staunch antirevisionist since 1978, admitted, after due consideration, that there was no evidence of the Nazi gas chambers’ existence. One could not fail to note, wrote Baynac, “the absence of documents, traces or other material evidence” (Le Nouveau Quotidien, Lausanne, September 2, 1996, p. 16, and September 3, 1996, p. 14).

Remark: all in all, J. Baynac says: “There is no evidence but I believe”, whereas a revisionist thinks “There is no evidence and so I refuse to believe and I dispute”; is one to be punished for not having the faith?

15) In 2000, at the end of her book Histoire du négationnisme en France (Gallimard, Paris), Valérie Igounet published a long text by Jean-Claude Pressac wherein the latter, taking up the words of professor Michel de Boüard, stated that the dossier on the concentration camp system was “rotten”, and irredeemably so. He wrote: “The current form, however triumphant, of the presentation of the camp universe is doomed”. He finished by surmising that all that had been invented around sufferings that were too real was bound “for the rubbish bins of history” (p. 651-652). In 1993-1994, that protégé of Serge Klarsfeld and Michael Berenbaum had been acclaimed worldwide as an extraordinary researcher who, in his book on Les Crématoires d’Auschwitz, la machinerie du meurtre de masse (CNRS éditions, Paris 1993; English title: The Auschwitz Crematories. The Machinery of Mass Murder), had, it appeared, felled the hydra of revisionism. Here, in V. Igounet’s book, he is seen signing his act of surrender.

Remark: if a dossier is irredeemably rotten and if so many of its components are bound for the rubbish bins of history, how can judges be expected to punish the disputing of it?

I, for one, have been convicted many times for having disputed the official version. My court convictions date from both before and after the Fabius-Gayssot Act’s appearance on the statute books. Nonetheless, over the years, the more I have re-offended, the lighter the sentences have become; sometimes, at the end, the examining magistrate has even decided to dismiss the charges, or the trial court or the court of appeal has pronounced an acquittal. It has reached the point where, although I have been prosecuted – unsuccessfully – for not having left a duty copy of my four-volume work of over 2,000 pages, produced in 1999 and entitled Écrits révisionnistes (1974-1998), at the Ministry of the Interior’s copyright bureau, the book’s contents themselves have earned me no prosecution. In the years since, I have not been taken to court for any of my revisionist publications. (Still, curiously, the hunt has just re-opened with an action brought by the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel [CSA, “radio and television supervisory council”], which denounced me earlier this year for having given a revisionist interview over the telephone to an Iranian television station: the trial is scheduled for June 20, 2006 in Paris).

G. Wellers and P. Vidal-Naquet were indignant at the Paris court of appeal’s decision of April 26, 1983. The former wrote: “The court admitted that Faurisson was well documented, which is false. It is astonishing that the court should fall for that” (Le Droit de vivre, June-July 1987, p. 13). The latter wrote that the Paris court “recognised the seriousness of Faurisson’s work – which is quite outrageous – and finally found against him only for having acted malevolently by summarising his theses as slogans” (Les Assassins de la mémoire, La Découverte, Paris 1987, p. 182; here quoted the English translation: Assassins of Memory, Columbia University Press, New York 1992). In 1986, gathered around French chief rabbi Sirat, those historians recommended the introduction of a specifically anti-revisionist law (Bulletin quotidien de l’Agence télégraphique juive, June 2, 1986, p. 1, 3). The Socialist Laurent Fabius and the Communist Jean-Claude Gayssot fulfilled their wishes in creating a law designed both to gag the revisionists and to tie the hands of the judges.

But the right to do historical research has no truck with fetters and muzzles.

October 1, 2005