The Zündel trials in Toronto (1985 and 1988)

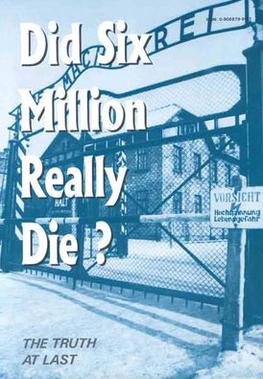

On May 13, 1988 Ernst Zündel was sentenced by judge Ronald Thomas of Toronto District Court to nine months’ imprisonment for having distributed a revisionist brochure that is now 14 years old: Did Six Million Really Die?

Zündel, 49, lives in Toronto where, up until a few years ago, he worked as a graphic artist and advertising man. A native of Germany, he has kept his German citizenship. His life has been through turmoil ever since the day when, in 1981, he began to distribute Did Six Million Really Die?, a revisionist work by Richard E. Harwood [pseudonym of Richard Verrall – ed.]. The booklet was first published in 1974 in Britain where, a year later, it was the focus of a lengthy controversy in the literary journal Books and Bookmen. Following an intervention of the South African Jewish community it was to be banned in South Africa. In Canada, after an initial trial in 1985 Zündel had been convicted and sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment. That sentence was quashed in 1987. A new trial had begun on January 18, 1988. I participated in the preparations for and the unfolding of these legal actions. I devoted thousands of hours to the defence of Ernst Zündel.

Already, the late François Duprat

In France secondary teacher François Duprat, as early as 1967, had published an article on “The Mystery of the Gas Chambers” (Défense de l’Occident, June 1967, p. 30-33). He was to become interested in the Harwood booklet, and then actively saw to its distribution. On March 18, 1978 he was killed by assassins equipped with means too complex not to be those of a secret service. Responsibility was claimed by a “Remembrance Commando” and by a “Jewish revolutionary group” (Le Monde, March 23, 1978, p. 7). Journalist Patrice Chairoff had published Duprat’s home address in Dossier néo-nazisme; he justified the killing in the columns of Le Monde (April 26, 1978, p. 9), where the victim’s revisionism inspired him to reflect: “François Duprat is responsible. There are responsibilities that kill.” In Le Droit de vivre, monthly of the LICRA (International league against racism and anti-semitism), Jean Pierre-Bloch expressed an ambiguous stance: he condemned the crime but, at the same time, let it be understood that there would be no pity for those who, following the victim’s example, might set out on the revisionist path (Le Monde, May 7-8, 1978).

Pierre Viansson-Ponté

Eight months before the assassination, journalist Pierre Viansson-Ponté had launched a virulent attack against Harwood’s brochure. His column was entitled “Le Mensonge” (The Lie), (Le Monde, July 17-18, 1978, p. 13). It was reprised with an approving commentary in Le Droit de vivre. Six months after the murder Viansson-Ponté went on the attack again in “Le Mensonge (suite)” (The Lie – continued) (Le Monde, September 3-4, 1978, p. 9). He passed over Duprat’s killing in silence; he disclosed the names and home towns of three revisionist readers and called for legal repression against revisionism.

Sabina Citron vs Ernst Zündel

In 1984 Sabina Citron, head of the Canadian Holocaust Remembrance Association, provoked violent demonstrations against Zündel. There was a bomb attack on his house. The Canadian postal service, likening revisionist literature to pornographic literature, had denied him the ability to send and receive mail, a right he would recover only after a year-long legal procedure. In the meantime his business had collapsed. At Sabina Citron’s instigation the Attorney General of Ontario lodged a complaint against Zündel for publishing a “false statement, tale or news”. The prosecution’s reasoning was as follows: the accused had abused his right to freedom of expression; by distributing the Harwood brochure, he was spreading information that he knew to be false; in effect, he could not be unaware that the “genocide of the Jews” and the “gas chambers” were established fact.

Zündel was also under a similar charge for having personally written and distributed a letter of the same inspiration as the brochure.

The first trial (1985)

The first trial lasted seven weeks. The jury found Zündel not guilty for his own letter but guilty for distribution of the brochure. He was sentenced by judge Hugh Locke to 15 months’ imprisonment. The German consulate in Toronto revoked his passport. The West German government prepared a deportation procedure against him. Previously the German authorities had launched throughout the country a gigantic one-day operation of police raids on the houses of all his German correspondents. In 1987 the United States would forbid him entry to its territory. But Zündel had won a media victory; day after day, for seven weeks, the entire English-language Canadian media had covered a trial that made spectacular revelations; it had emerged that the revisionists possessed documentation and arguments of primal force, while the exterminationists were at bay.

Their expert: Raul Hilberg

At this first trial the prosecution’s expert was Raul Hilberg, an American professor of Jewish origin, author of a reference work: The Destruction of the European Jews (1961) that Paul Rassinier discusses in Le Drame des Juifs européens. Witness Hilberg began by seamlessly developing his theory of the extermination of the Jews. Then came his cross-examination conducted by Zündel’s barrister, Douglas Christie, with the assistance of Keltie Zubko and myself. Right from the first questions it was revealed that Hilberg, who was the highest world authority on the history of the Holocaust, had never examined a single concentration camp, not even Auschwitz. He had done so neither before publishing his book in 1961 nor since that date. In 1985, when he was announcing the imminent release of a new edition in three volumes, revised, corrected and augmented, he had still examined no camps. He had been to Auschwitz in 1979 for a single day to attend a ceremony. He had not had the curiosity to examine either the buildings or the archives. In all his life he had not seen a “gas chamber”, either in its “original state” or in a state of ruins (for the historian, ruins are always telling). He was cornered into acknowledging that there had been, for what he called the policy of extermination of the Jews, neither a plan, nor a central organisation, nor a budget nor financial oversight. He then had to admit that, since 1945, the Allies had never carried out any forensic study of “the crime weapon” finding that a homicidal gas chamber had existed. No post-mortem had found that an inmate was killed by poison gas.

Hilberg affirmed that Hitler had given orders for the extermination of the Jews and that Himmler, on November 25, 1944 (what precision!), had given an order to halt that extermination, but he was unable to produce those orders. The defence asked him whether, in the new edition of his book, he still maintained the existence of those orders of Hitler. He dared to answer yes. He was lying. He was, indeed, committing perjury. In that new edition (preface dated September 1984), Hilberg systematically deleted any mention of an order from Hitler. (In this regard, see the review by Christopher Browning, The Revised Hilberg, Simon Wiesenthal Center Annual, 1986, p. 294). When asked by the defence to explain how the Germans, bereft of any plan, had been able to conduct successfully a gigantic enterprise like that of the extermination of millions of Jews, he replied that there had been in the various Nazi bodies “an incredible meeting of minds, a consensus mind-reading by a far-flung bureaucracy“.

Witness Arnold Friedman

The prosecution was counting on the testimony of “survivors”. These “survivors” had been chosen with care. They were going to prove that they had seen, with their own eyes, preparations for and procedures of homicidal gassings. Since the war, in a series of trials like those at Nuremberg (1945-1946), Jerusalem (1961) or Frankfurt (1963-65), such witnesses had never been wanting. However, as I have often pointed out, no lawyer for the defence had ever had the courage or the competence needed to cross-examine these witnesses on the gassings themselves.

However, for the first time, in Toronto, in 1985, one lawyer, Douglas Christie, dared to ask for explanations; he did so [thanks to my documentation] with the help of topographical maps and building plans as well as scientific documentation on both the properties of the gases supposedly used and on the capacities of cremation, whether in crematory ovens or on pyres. Not one of these witnesses stood the test, and especially not Arnold Friedman. This man, in desperation, ended up confessing that he had indeed been at Auschwitz-Birkenau (where, by the way, he never had to work, apart from once to help unload a shipment of potatoes), but that, as concerned gassings, he had relied on hearsay.

Witness Rudolf Vrba

Witness Rudolf Vrba was internationally known. A Slovak Jew, interned at Auschwitz and at Birkenau, he had, said he, escaped from the camp in April 1944 together with Fred Wetzler. Back in Slovakia, he had dictated a report on Auschwitz, on Birkenau, on their crematoria and their “gas chambers”.

Through the intermediary of Jewish organisations in Slovakia, Hungary and Switzerland, this report reached Washington, where it served as the basis for the American government’s famous War Refugee Board Report of November 1944. Thus every Allied organisation charged with the prosecution of “war crimes” and every Allied prosecutor involved in trials of “war criminals” were to have at their disposal the official version of those camps’ history.

Vrba later became a British citizen and published his autobiography under the title I Cannot Forgive; this book, published in 1964, had actually been written by Alan Bestic who, in his preface, paid tribute to Vrba’s “considerable care for each detail” and to his “meticulous and almost fanatical respect for accuracy”. On November 30, 1964 Vrba testified at the Frankfurt trial. Then he settled in Canada and took out Canadian citizenship. He appeared briefly in various films on Auschwitz, particularly Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah. Everything smiled on this witness until the day when, in 1985, at the Zündel trial, he was bluntly cross-examined. He then showed himself to be an impostor. It was disclosed that, in his 1944 report, he had completely made up the number and location of the “gas chambers” and the crematoria. His 1964 book opened with a visit by Heinrich Himmler to Birkenau for the inauguration, in January 1943, of a new crematorium with “gas chamber”; however, Himmler’s last visit there took place in July 1942 and, in January 1943, the first of the new crematoria was far from finished. Thanks, apparently, to “special mnemonic principles” or a “special mnemonical method”, and thanks to a veritable gift of ubiquity, Vrba had calculated that in the space of 25 months (April 1942 to April 1944) the Germans had “gassed” in the Birkenau camp alone 1,765,000 Jews, amongst whom 150,000 Jews from France. However, Serge Klarsfeld, in 1978, in his Mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France, had to conclude that, in the entire length of the war, the Germans had deported to all the concentration camps a total of 75,721 Jews from France. The gravest aspect of this is that the figure of 1,765,000 Jews “gassed” at Birkenau had been adopted in a document (L-022) of the Nuremberg Tribunal. Pinned down on all sides by Zündel’s lawyer, the impostor had no other recourse than to invoke, in Latin, licentia poetarum, poetic license, the right to fiction. His book has just been published in French, presented as written by “Rudolf Vrba with Alan Bestic”; it no longer contains Alan Bestic’s enthusiastic preface; in the short presentation by Emile Copfermann it is said: “with the approval of Rudolf Vrba the two appendices from the English edition have been removed”. There is no mention of the fact that those two appendices had also earned our man some serious trouble in 1985 at the Toronto trial.

The second Zündel trial (1988)

In January 1987 a five-member appeal panel decided to nullify the 1985 trial for reasons of substance: judge Locke had not allowed the defence any guarantee in the selection of the jury and the jury had been deceived by the judge about the very meaning of the trial. Personally, I have attended numerous trials in my life, including some held in France during the “Purge” at the end of and after the war. Never have I encountered a judge so partial, autocratic and violent as Hugh Locke. The English-based justice system offers many more guarantees than the French but it can take just one man to pervert the best of systems. Judge Locke was that man.

The second trial began on January 18, 1988 under the direction of judge Ron Thomas, who is a friend, it seems, of judge Locke. Judge Thomas is choleric, downright hostile to the defence but he has more finesse than his predecessor; also, the observations of the five senior judges are there, holding him back a bit. Locke had imposed numerous restrictions on the defence witnesses’ and experts’ free expression; he had, for example, forbidden me to use any of the photos I had taken at Auschwitz; I had not had the right to employ arguments of a chemical, topographical or architectural order (this when I had been the first in the world to publish the plans for the Auschwitz and Birkenau crematoria); I had not been able to talk about either the American gas chambers or the aerial reconnaissance photos of Auschwitz and Birkenau. Even an eminent chemist like William Lindsey had been bridled in his deposition. Judge Thomas, for his part, would allow the defence more freedom but at the outset, at the prosecution’s request, he took a decision of a kind to tie the hands of the jury.

Judge Thomas‘s judicial notice

In the English-based legal systems all must be proved save certain obvious facts (“The capital of Britain is London”, “day follows night”… ) And the judge must take “judicial notice” of these obvious facts at either party’s request.

Prosecutor John Pearson asked the judge to take judicial notice of the Holocaust. That term remained to be defined. It is likely that, if not for the intervention of the defence, the judge would have defined the Holocaust as one might have been defined it in 1945-1946. In that period the “genocide of the Jews” (the word “Holocaust” had not yet come into use) could have been defined as “the ordered and planned destruction of six million Jews, in particular through the use of gas chambers”.

The trouble for the prosecution was that the defence notified the judge that, since 1945-1946, some profound changes had been made in the exterminationist historians’ own idea of the extermination of the Jews. To begin, they no longer talked about an extermination but about an attempt at extermination. Then they had ended up admitting that, “despite the most erudite research” (Raymond Aron, Sorbonne symposium, July 2, 1982), no trace of any order to exterminate the Jews had been found. Then came the split between the “intentionalists” and the “functionalists”: all were agreed that there was no proof of an exterminatory intent, but the historians of the first school deemed that the existence of that intent must nevertheless be supposed, whereas the historians of the second school considered the extermination to have been the fruit of individual, local and uncontrolled initiatives: the function had, as it were, created the organ! Lastly, the six million figure had been declared “symbolic” and there had been a good number of dissensions on the “problem of the gas chambers”.

Judge Thomas, obviously surprised by this flood of information, decided to take a cautious approach and, after a cooling-off period, opted for the following definition; the Holocaust, he said, was “the extermination and/or mass-murder of Jews” by National Socialism. This definition was remarkable on more than one account: in it there was no more trace of an extermination order, or of a plan, or of “gas chambers”, or of six million Jews or even of millions of Jews. It was void of all substance to the point of no longer corresponding to anything, for one can hardly see, in following it, what a “mass-murder of Jews” (the judge had carefully avoided saying “of the Jews”) might actually be. This definition, by itself, made it possible to gauge the progress made by historical revisionism from 1945 to 1988.

Raul Hilberg refuses to appear

A misfortune awaited Prosecutor John Pearson: Raul Hilberg, despite repeated requests, refused to appear anew. The defence, having heard rumours of an exchange of correspondence between Pearson and Hilberg, demanded and obtained disclosure of the letters exchanged and, in particular, of a “confidential” letter of Hilberg’s in which the latter did not conceal the fact that he had an unpleasant memory of his 1985 cross-examination. Hilberg dreaded lest Douglas Christie repeat his performance on the same points on which he had examined him then. In the words of his confidential letter he wrote that he feared “every attempt to entrap me by pointing out any seeming contradiction, however trivial the subject might be, between my earlier testimony and an answer that I might give in 1988”. In fact, as I have said above, Hilberg had committed outright perjury and could not but fear charges of perjury.

Christopher Browning, prosecution witness

In place of Hilberg there came his friend Christopher Browning, an American professor, specialist of the Holocaust. Admitted as an expert witness (and paid for several days at the rate of $150 per hour by the Canadian taxpayer), Browning strove to prove that Harwood’s brochure was a tissue of lies and that the attempt to exterminate the Jews was a scientifically established fact. This turned out badly for him. During the cross-examination the defence used his own arguments to annihilate him. In the course of those days the tall and naive professor, who at first swaggered as he stood, was seen taking his seat and shrinking up behind the witnesses’ lectern like a schoolboy caught in mischief. With a faint and submissive voice he ended up acknowledging that, decidedly, this trial had taught him something about historical research.

Just like Hilberg, Browning had not examined any concentration camps. He had not visited any “gas chamber” sites. The idea of seeking or requesting a forensic study of the “crime weapon” had never occurred to him. In his writings he made much of the homicidal “gas vans”; however, he was unable to refer to any true photograph, any plan, any technical study, any forensic study. He was not aware that German words such as Gaswagen, Spezialwagen, Entlausungswagen (delousing van) could have a perfectly benign meaning. His technical knowledge was nil. He had never examined the aerial reconnaissance photos of Auschwitz. He knew nothing of the tortures endured by the Germans who, like Rudolf Hoss, had spoken of gassings. He was ignorant of the doubts expressed on some of Himmler’s speeches or on the Goebbels diary.

A big enthusiast of the war criminal trials, Browning had questioned only the prosecutors and never the defence lawyers. His ignorance of the Nuremberg trial proceedings was astounding. He had not even read what Hans Frank, former Governor General of Poland, had said before the Nuremberg tribunal about his “diary” and about “the extermination of the Jews”. Inexcusable! Actually, Browning claimed to have found in Frank’s “diary” irrefutable proof of the existence of a policy of exterminating the Jews. He had discovered one incriminating sentence. He did not know that Frank had provided the Tribunal with an explanation of this type of sentence, taken from among the hundreds of thousands of sentences of an 11,560-page personnel and administrative diary. Furthermore, Frank had spontaneously handed over this “diary” to the Americans come to arrest him. To anyone who reads his deposition, the sincerity of the former Governor General is so exempt from doubt that it will seem only normal that Browning, invited to hear the diary’s content, accepted without the least objection.

One last humiliation awaited him.

For the purposes of his thesis he had invoked a passage from the “protocol” of the Wannsee conference (January 20, 1942); he had given his own translation of it; the translation was seriously faulty. On this account, his thesis collapsed. Finally, as for his personal explanation of a “policy of exterminating the Jews”, it was worth the same as Hilberg’s: for Browning all was explained by “the nod” of Adolf Hitler – by which one is supposed to perceive that the Führer of the German people had had no need to give a written order or a verbal order for the extermination of the Jews: it had sufficed to give a “nod” at the outset of the operation and, for what followed, a series of “signals”. And he had been understood!

Charles Biedermann

The other expert, called by the prosecution before Browning, was Charles Biedermann, a Swiss citizen, a delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and, above all, director of the International Tracing Service (ITS) in Arolsen, West Germany. The ITS possesses an amazing wealth of information on the individual fate of victims of National Socialism and, in particular, of former concentration camp inmates. I claim that it is at Arolsen that the real number of Jews who died during the war could be determined.

The prosecution got no benefit, so to speak, from this expert’s deposition. Conversely, the cross-examination allowed the defence to score a number of points. Biedermann acknowledged that the ICRC had never found evidence of the existence of homicidal gas chambers in the German camps. The fact-finding visit to Auschwitz by one of its delegates in September 1944 had concluded, on that subject, no more than the existence of a rumour. To his embarrassment, the expert was bound to admit that he committed an error in ascribing to the National Socialists the expression “extermination camps”; he had not realised that this was an expression coined by the Allies. He claimed that the ICRC had shown itself to be impartial during and after the conflict; he was shown otherwise. After the conflict the ICRC had joined in chorus with the Allies.

Biedermann stated that he was unaware of the ICRC’s reports on the atrocities visited on the Germans towards the war’s end and just afterwards; in particular, he knew nothing about the appalling treatment reserved for many German prisoners of war. It seems that the ICRC possessed nothing on the massive deportations of German minorities from the East, nothing on the horrors of the “the great debacle” in Germany, nothing on the summary executions and, in particular, the massacre by rifle or machine gun fire or by beating with shovels or pickaxes of 520 German soldiers and officers who had surrendered to the Americans at Dachau on April 29, 1945 (even though ICRC delegate Victor Maurer was there).

The ITS classified as “persecuted” by the Nazis even the common criminals who had ended up in concentration camps. He trusted the data of the “Auschwitz Museum” (a communist entity). Since 1978, in order to hinder any revisionist research, the ITS had closed its doors to historians and researchers, except those with a special authorisation from one of the ten governments (amongst which that of Israel) that oversee the ITS’s activity. Henceforth the Tracing Service was forbidden to make, as it had done up to then, statistical evaluations of the number of dead in the various camps. The valuable annual activity reports were no longer to be made available to the public, except for the first third of them which is of no interest for the researcher.

Biedermann confirmed news that had filtered out in 1964 at the Frankfurt trial: at the liberation of Auschwitz, the Soviets and the Poles had discovered the death register of that complex of 39 camps and sub camps. The register consisted of 38 or 39 volumes. The Soviets keep 36 or 37 of these volumes in Moscow while the Poles keep two or three others at the “Auschwitz Museum”, a copy of which they have supplied to the ITS in Arolsen. But neither the Soviets nor the Poles nor the ITS authorises consultation of these volumes. Biedermann did not even want to reveal the number of dead counted in the two or three volumes of which the ITS possesses a copy. It is clear that making the content of the Auschwitz death register public would mean the end of the myth of that camp’s millions of deaths.

No “survivors” for the prosecution

The judge asked the prosecutor whether he would be calling any “survivors” as witnesses. The prosecutor answered no. The experience of 1985 had been too cruel. The ordeal of the cross-examination had been devastating. It is regrettable that in France, at the trial of Klaus Barbie (1987), and in Israel, at the trial of John Demjanjuk (1987-1988), no defence lawyer followed the example given by Douglas Christie in the first Zündel trial (1985): Christie had demonstrated that, with a cross-examination on the “gassing” procedure itself, the “extermination camp” myth could be destroyed at the root.

The defence’s witnesses and experts

Most of the witnesses and experts for the defence were as precise and materialist as a Hilberg or a Browning had been imprecise and metaphysical. The Swede Ditlieb Felderer showed about 350 slides of Auschwitz and other camps in Poland. The American Mark Weber, whose knowledge of the documents is impressive, proceeded to develop several aspects of the Holocaust and, in particular, of the Einsatzgruppen.* The German Tijudar Rudolph dealt with the Lodz ghetto; he also gave a personal testimony about a tour of inspection by the ICRC in the camps of Silesia and the General Government of Poland (Auschwitz, Majdanek,…) in Autumn 1941, at the end of which the ICRC delegate thanked Hans Frank, the Governor General, for his cooperation.

In 1944 Thies Christophersen had led an agricultural research enterprise in the Auschwitz region; he often visited the Birkenau camp to requisition personnel; he had never noted there the horrors usually described. In the box he took up again, point by point, what he had described, starting in 1973 in a 19-page report (Kritik, no. 23, p. 14-32).

The Austrian-born Canadian Maria Van Herwaarden had been interned at Birkenau from 1942; she had seen nothing, either directly or indirectly, that resembled mass murder but many internees had died of typhus. The American Bradley Smith, member of a “Committee for Open Debate on the Holocaust“, related his experience of more than 100 discussions on American radio and television on the subject of the Holocaust.

The Austrian Emil Lachout commented on the famous “Müller Document” which, since December 1987, has agitated the Austrian authorities: this document, dated October 1, 1948, reveals that, already at that date, the Allied commissions of inquiry no longer believed in the homicidal “gassings” in a whole series of camps – Dachau, Ravensbrück, Struthof (Natzweiler), Stutthof (Danzig), Sachsenhausen and Mauthausen (Austria). The document specifies that confessions of Germans had been extracted under torture and that the testimonies were false.

Dr Russell Barton recounted his horrified discovery of the Bergen-Belsen camp at liberation; at the moment he had believed in a deliberate massacre, then he realised that, in a Germany of apocalypse, those heaps of corpses and those walking skeletons were the result of the horrid conditions of an overcrowded camp ravaged by epidemics, deprived of water following an Allied bombardment, almost wholly bereft of medicine and supplies.

The German Udo Walendy detailed his research into the many forgeries he had unearthed in wartime atrocity photographs and other documents, either altered or created by a team headed by British propagandist Sefton Delmer.

J. G. Burg, mosaic Jew living in Munich, related his experience of the war and proved that there had never existed a policy of extermination of the Jews by the Nazis.

Academics Kuang Fu and Gary Botting brought their contribution in terms of analyses of historical facts, opinions and interpretations. Jürgen Neumann explained the nature of the research he had carried out alongside Ernst Zündel. Ernst Neilsen testified on the hindrances to free research into the Holocaust brought to bear by a Canadian university. Ivan Lagacé, director of the crematory in Calgary (Alberta, Canada), demonstrated the practical impossibility of the figures given by Hilberg for cremations at Auschwitz.

For my part, I gave a deposition as expert for nearly six days. I insisted particularly on my investigations regarding the American gas chambers. I recalled that Zyklon B is basically hydrocyanic acid and that it is with this gas that certain American penitentiaries execute condemned prisoners.

In 1945 the Allies should have asked specialists of the American gas chambers to examine the buildings that, at Auschwitz and elsewhere, were supposed to have been used to gas millions of detainees. From 1977 my idea was as follows: when dealing with a vast historical problem like that of the reality or legend of the Holocaust, one must strive to find the core of the problem; in the circumstances, the centre is the problem of Auschwitz and, in its turn, the core of that problem can be limited to a space of 275 square metres, that is, at Auschwitz, the 65 square metres of the “gas chamber” of crematorium-I and, at Birkenau, the 210 square meters of crematorium-II’s “gas chamber”. In 1988 my idea remained the same: let us appraise the 275 square metres and we shall have an answer to the vast problem of the Holocaust! I showed the jury my photos of the gas chamber of the Maryland State Penitentiary in Baltimore as well as my copies of the building plans for the Auschwitz “gas chambers”, and I underlined the physical and chemical impossibilities of the latter.

A sensational turn of events: The Leuchter Report

Zündel, in possession of the correspondence I had exchanged in 1977-78 with the six American penitentiaries outfitted with gas chambers, tasked barrister Barbara Kulaszka with getting in touch with the governors of those prisons in order to see whether one of them would agree to come and explain in court a real gas chamber’s mode of operation. Mr Bill Armontrout, warden of Jefferson City (Missouri) penitentiary, agreed to come testify and pointed out that nobody in the United States was more familiar with the functioning of those gas chambers than an engineer from Boston: Fred A. Leuchter. I went to visit that engineer on February 3 and 4, 1988. Leuchter had never asked himself any questions about the “gas chambers” of the German camps. Up until then he believed in their existence. Once I began opening my files he realised the material and chemical impossibility of the “gassings”. He agreed to come to Toronto and examine our documents.

After that, funded by Zündel, he departed for Poland with a secretary (his wife), his draftsman, a video-cameraman and an interpreter. He returned to draw up a 192-page report (including appendices), and now also had with him 32 samples taken, on the one hand, from the crematoria of Auschwitz and Birkenau (supposed location of the homicidal “gassings”) and, on the other, from a Birkenau delousing gas chamber. His finding was clear-cut: there had been no homicidal “gassing” either at Auschwitz, Birkenau or Majdanek.

On April 20 and 21, 1988 Fred Leuchter made his deposition in the Toronto court. He told the story of his investigation and elaborated on his finding. I can say that, during those two days, I attended the death on the spot of the gas chamber myth, a myth that, for me, had entered its death throes at the Sorbonne symposium on “Nazi Germany and the extermination of the Jews” (June 29 to July 2, 1982), where the organisers themselves started to grasp that there was no proof of the existence of the gas chambers.

In the courtroom emotions were intense, particularly among the friends of Sabina Citron. Ernst Zündel’s friends were also deeply moved but for other reasons: they were at last seeing the veil of the great imposture being torn up. As for me, I felt both relief and melancholy: relief because a thesis I had been defending for so many years was at last attaining full confirmation, and melancholy because I had fathered the idea; I had even, with the awkwardness a literary man might show in such a venture, expounded on physical, chemical, topographical and architectural arguments that I was now seeing taken up by a scientist who was astonishingly precise and instructive. Would the scepticism I had encountered, also among certain revisionists, be remembered?

Just before Leuchter, Bill Armontrout had come to the witness box and confirmed altogether what I had said to the jury about the extreme difficulties of a homicidal gassing (not to be confused with a suicidal or accidental gassing). At his end, Ken Wilson, an aerial photography specialist, had shown that the homicidal “gas chambers” of Auschwitz and Birkenau did not have the gas evacuation chimneys that would have been indispensable. He also showed that I had been right to accuse Serge Klarsfeld and Jean-Claude Pressac of falsifying the map of Birkenau in the “Auschwitz Album” (Le Seuil, Paris 1983, p. 42). Those authors, in order to have the reader believe that the groups of Jewish women and children, surprised by a photographer while on their way between crematoria II and III, could continue no farther and were thus bound for those crematoria’s “gas chambers”, had simply cut out of the map the path that, in reality, led to the “Zentralsauna”, a big shower facility (located beyond the crematoria zone) where those women and children were heading.

James Roth, director of a laboratory in Massachusetts, came up to testify on the analysis of the 32 samples, of whose origin he was unaware: all the samples taken in the homicidal “gas chambers” contained a quantity of cyanide that was either undetectable or infinitesimal, while the sample from the disinfestation gas chamber of Birkenau, taken for reference, contained by comparison an enormous quantity of cyanide (the infinitesimal quantity detected in the former case can be explained by the fact that the alleged homicidal gas chambers were in fact cold rooms for preserving bodies; such cold rooms could have been treated for disinfestation with Zyklon B).

David Irving

The British historian David Irving enjoys great prestige. Zündel thought of asking him to testify, but there was a problem: Irving was only half revisionist. The thesis he defended, for example in Hitler’s War (Viking Press, New York 1977), can be summed up as follows: Hitler never gave an order for the extermination of the Jews; at least up to the end of 1943 he was kept in ignorance of that extermination; only Himmler and a group of about 70 persons were informed; in October 1944 Himmler, who henceforth was seeking to get into the western Allies’ good graces, had give an order to cease the extermination of the Jews.

I had personally met Irving in Los Angeles in September of 1983 at the annual convention of the Institute for Historical Review and had put him on the spot with a few questions about the evidence he had to support his argument. Then I had published an article entitled A Challenge to David Irving in the Journal of Historical Review (Winter 1984, p. 289-305, and Spring 1985, p. 8 and 122). In it I tried to convince this brilliant historian that, logically, he could no longer content himself with a semi-revisionist position and, to begin, I challenged him to produce that order from Himmler which, in reality, had never existed. Afterwards I learned from various sources that Irving was undergoing a mutation in a direction favourable to revisionism.

In 1988 Zündel became convinced that the British historian was only waiting for some decisive event before taking a last step in our direction. On arriving in Toronto, Irving discovered in rapid succession the Leuchter report and an impressive number of documents that Zündel, his friends and I had accumulated in the course of several years. The last reservations or the last misunderstandings dissipated in the course of a meeting. He agreed to testify in court. In the opinion of those who attended the two trials (of 1985 and 1988), no single testimony, except that of Leuchter, caused such a sensation. For more than three days Irving, engaging in a sort of public confession, took back all he had said about the extermination of the Jews, and without reservation rallied to the revisionist position. With courage and probity, he showed how a historian can be led to make a radical revision of his views on the history of the Second World War.

Ernst Zündel’s victory

Ernst Zündel had promised that his trial would be “the trial of the Nuremberg trial” or “the exterminationists’ Stalingrad”. The unfolding of those two long trials proved him right, even though the jury, “instructed” by the judge and summoned to consider the Holocaust to be an established fact “which no reasonable person can doubt”, proceeded to find him guilty. Zündel has already won. It remains for him to make it known to Canada and the whole world. For the 1988 trial the media black-out was almost complete. Jewish organisations had campaigned to secure that blackout and had gone so far as to say they did not want to see an impartial account of the trial. They did not want there to be any account. The paradox is that the only publication covering the trial in a relatively honest manner should be the Canadian Jewish News.

Ernst Zündel and the Leuchter report have entered History; they will not be leaving it soon.

December 1, 1988

________________

* Weber also clarified the meaning of the term “Final Solution” (emigration or deportation, but never extermination, of Jews): the testimony of Judge Konrad Morgen; the tortures endured by Rudolf Höss and Oswald Pohl; the true history of revisionism; and the concessions to the revisionist viewpoint made year after year by the exterminationists.