Letter on my discovery of the Auschwitz crematoria building plans

to Lady Michèle Renouf

Dear Michèle,

Yes, I am the one who discovered the plans of the Auschwitz crematoria. It was in 1976 on my second visit to the camp; my first visit was in 1975.

I haven’t the time to explain to you how I managed to find, on March 19, 1976, all those plans and many other items at the Auschwitz archives centre, where I met Tadeusz Iwaszko, chief archivist at the Auschwitz State Museum.

For years I tried to publish the plans in question. Impossible. One day a friend told me he knew a Spanish journalist who perhaps would agree to publish an interview with me, along with some photos. The newspaper was the Spanish magazine Interviú. The journalist was Vicente Ortuno and the photographer was Jean-Marie Pulm. They came to Vichy. They promised me and my friend not to publish any photo of my face, and that an agreement would be signed before any publication. In fact they lied. They quickly published what you can see in Interviú (February 22-28, 1979, p. 64-66; please see the reproductions below). In the article I am described as a sadistic Nazi. I have the French translation of that article but it is of no interest. I filed a lawsuit in Paris. I won my case but the amount of damages was ridiculous (the presiding judge was a Jewess by the name of Simone Rozès).

So it was that the Holo Believers had been sitting on those plans for over 30 years after the war. Question: “How is it that the Jews and the Communists decided to hide the plans showing the alleged crime weapon?” The answer is that those plans showed clearly that the alleged homicidal gas chambers were rooms designed and used as mortuaries (or places to keep bodies before their incineration), exactly as, for example, in the Sachsenhausen camp near Berlin (there, the big Leichenkeller was made up of three different rooms: one for bodies in coffins, one for bodies not in coffins and another, equipped with a special isolation system, for contaminated bodies). This kind of place was called a Leichenhalle (“corpse hall”) or Leichenkeller (“corpse cellar”).

Isn’t it odd that the man who had discovered and tried to publish such things was a revisionist, i.e. a non-believer?

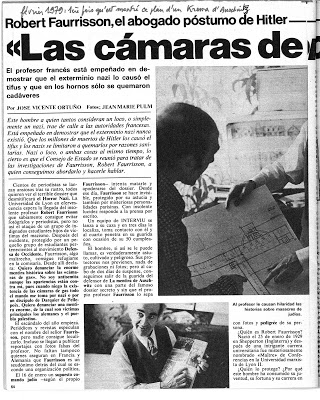

In the large photo in Interviú I am seen showing Leichenkeller 1 of crematorium II in Auschwitz-Birkenau; that crematorium was situated near the football field (Sportplatz) where the inmates played soccer matches; sometimes the ball fell into the courtyard of the crematorium and had to be retrieved from there.

In the same photo, behind me can be seen two other plans.

On March 19, 1976 I ordered and paid for 116 photos (I still have the bill) but afterwards I had some serious trouble getting them sent from Poland to Vichy. I had to ask the French Consulate in Cracow to intervene. Of course, to none of those people in Communist Poland had I disclosed that I was a revisionist.

In the smaller photo I am showing Serge Klarsfeld’s book, Mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France (1978), and explaining some of the tricks played by that fraudster in his book.

As soon as they learnt of the Interviú article, the Holo Believers began publishing the same drawings but not without explaining to readers that they had to understand that the German terms were code words which, consequently, needed decoding. Jean-Claude Pressac harboured a predilection for that sort of job, particularly in his enormous book entitled Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the gas chambers, published in 1989 by the Beate Klarsfeld foundation in New York. But, as you probably know, Pressac ended up recanting his views and, on June 15, 1995 (a month after I had made him testify in a case brought against me [for my Réponse à Jean-Claude Pressac (1994)], signed a paper in which he finally said that the official version of Nazi concentration camp history was “rotten” (pourri) and good only for the “rubbish bins of history” (poubelles de l’histoire). That recantation of his was kept hidden for five years and made public only in March 2000 by a conventional historian, Valérie Igounet, at the very end of her book, Histoire du négationnisme en France, Seuil (Paris), p. 651-652.

Best wishes,

Robert Faurisson

Vichy, July 13, 2009