Is The Diary of Anne Frank genuine?

Publishers’ note (1980)

The report you are about to read was not meant for publication. As Professor Faurisson conceived it, it made up only one part, amongst others, of a work he intended to devote to the Diary of Anne Frank.

If we publish it today, despite the reticence of its author who, for his part, would rather have seen the publication of a more extensive work comprising elements that are still in preparation, it is because the French press and the foreign press have made something of a row about the Professor’s opinion on the Diary of Anne Frank, and the public, for its part, may feel the need to judge on actual evidence. Therefore we have preferred to put the gist of that evidence at the public’s disposal. Readers will thus be able to make up their own minds on Faurisson’s methods of work and on the results at which he arrived in August 1978.

This report, in the exact form* in which we publish it, already has an official existence. It was in August 1978 that it was transmitted, in its German version, to barrister Jürgen Rieger to be filed with a court in Hamburg. Mr Rieger was and is still today the defender of Ernst Römer, brought to trial for having publicly expressed his doubts about the authenticity of the Diary.

______________________

* Author’s note (16 May 2010): With one exception. The original report included an appendix 3 consisting of an attestation from a university professor, Michel Le Guern, noted for his proficiency in the appraisal of texts. That attestation’s closing sentence read: “It is certain that the practices of literary communication authorise Mr Frank, or anyone else, to construct as many fictional figures of Anne Frank as he may like, but on condition he not assert that the figure of his daughter is identical to any of those fictive beings.” Each page of my report bore Pr Le Guern’s signature or initials. Two other academics, Frédéric Deloffre and Jacques Rougeot, were about to find along the same lines when suddenly, in November 1978, the “Faurisson affair” flared up in the press. Rendered prudent by the circumstances, they preferred to refrain. For more details the reader is referred to the postscript below dated 1 April 2003.

***

Author’s note (1997)

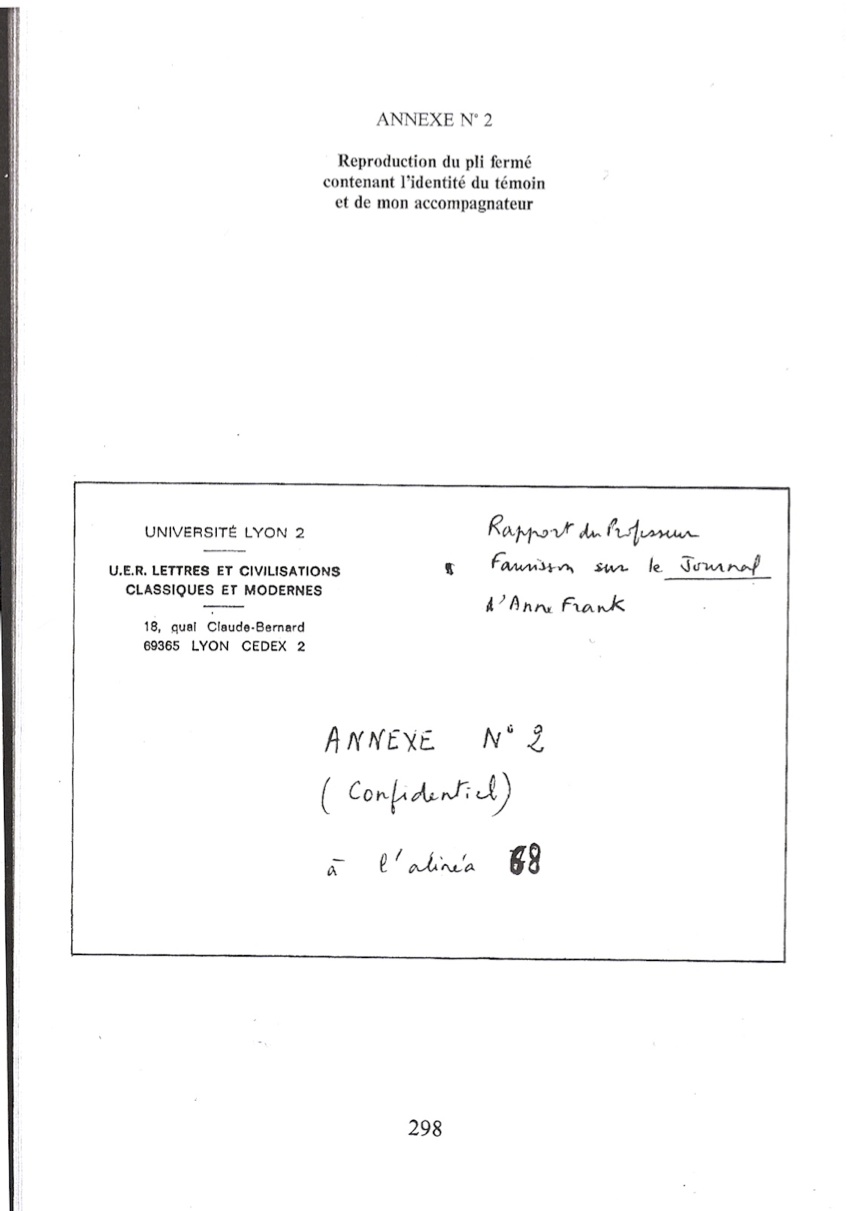

This report, expressly intended for a court of law, was accompanied by three appendices.

The first contained fourteen photographic documents [reproduced below after the aforementioned postscript].

The second contained, in a sealed envelope, the name of the witness in the Karl Silberbauer case (section 68 below) and that of the person accompanying me; today I am able to reveal that the two were, respectively, the widow Mrs Silberbauer and Mr Ernst Wilmersdorf, both of Vienna.

The court, having heard the parties and begun to examine the basis of the litigation, decided, to everyone’s surprise, to adjourn the case sine die.

In keeping with usual practice, from the trial’s opening the press dictated to the court the conduct to adopt. Chancellor Helmut Schmidt’s Social Democratic party went onto the frontline of the battle and, in a long open letter, vigorously took a position in Mr Frank’s favour. For that political party the case was decided beforehand and the Diary‘s authenticity had been proved a long time ago.

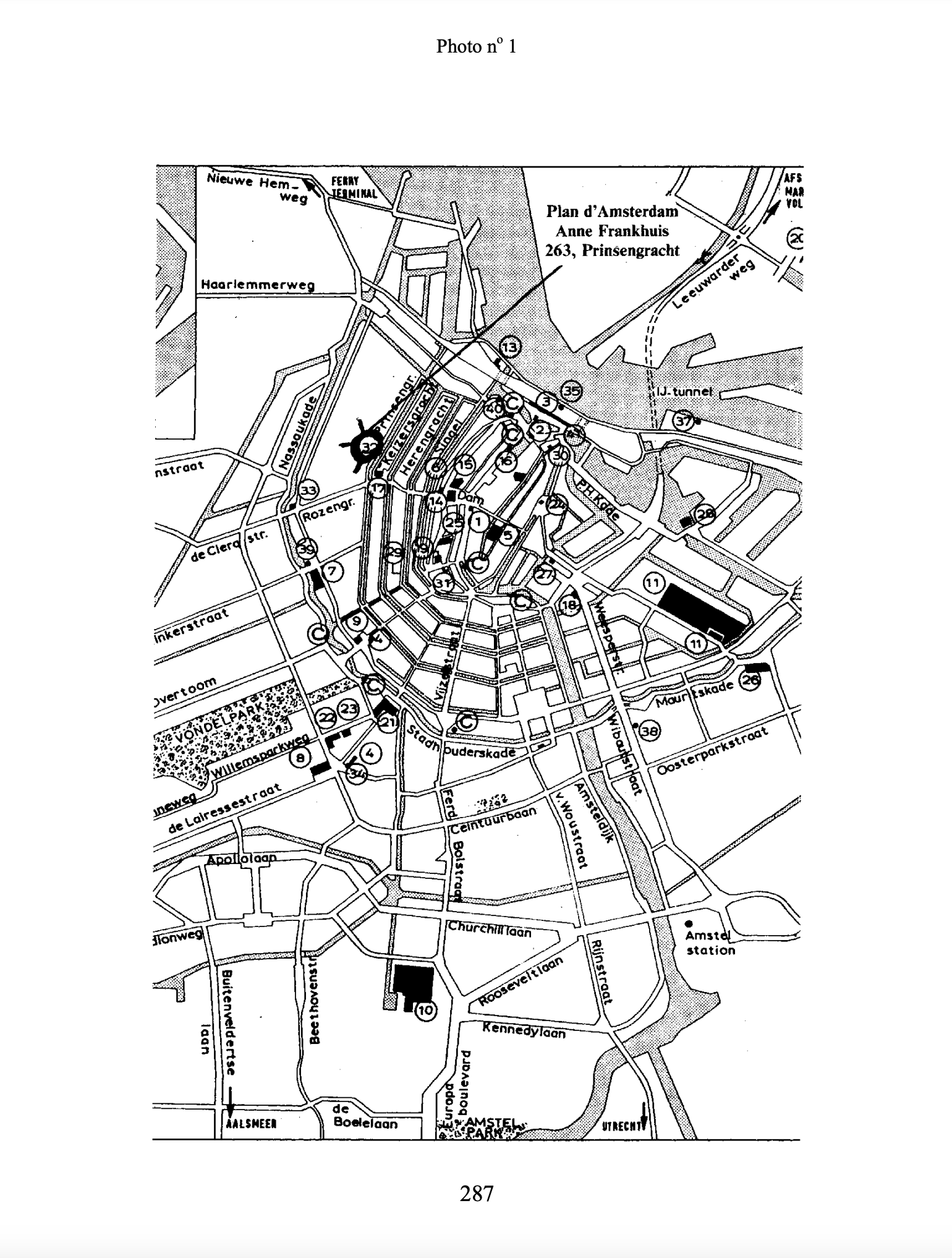

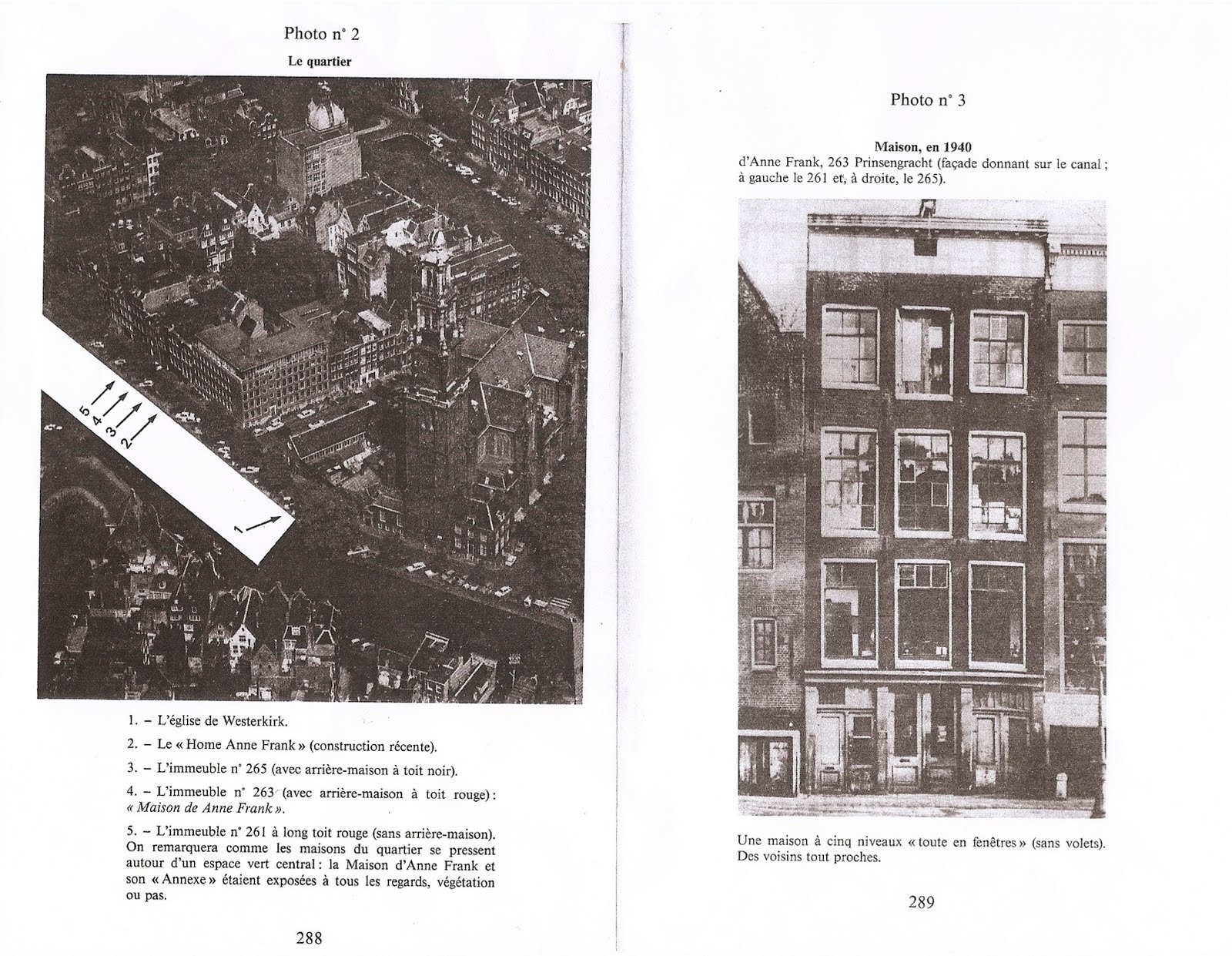

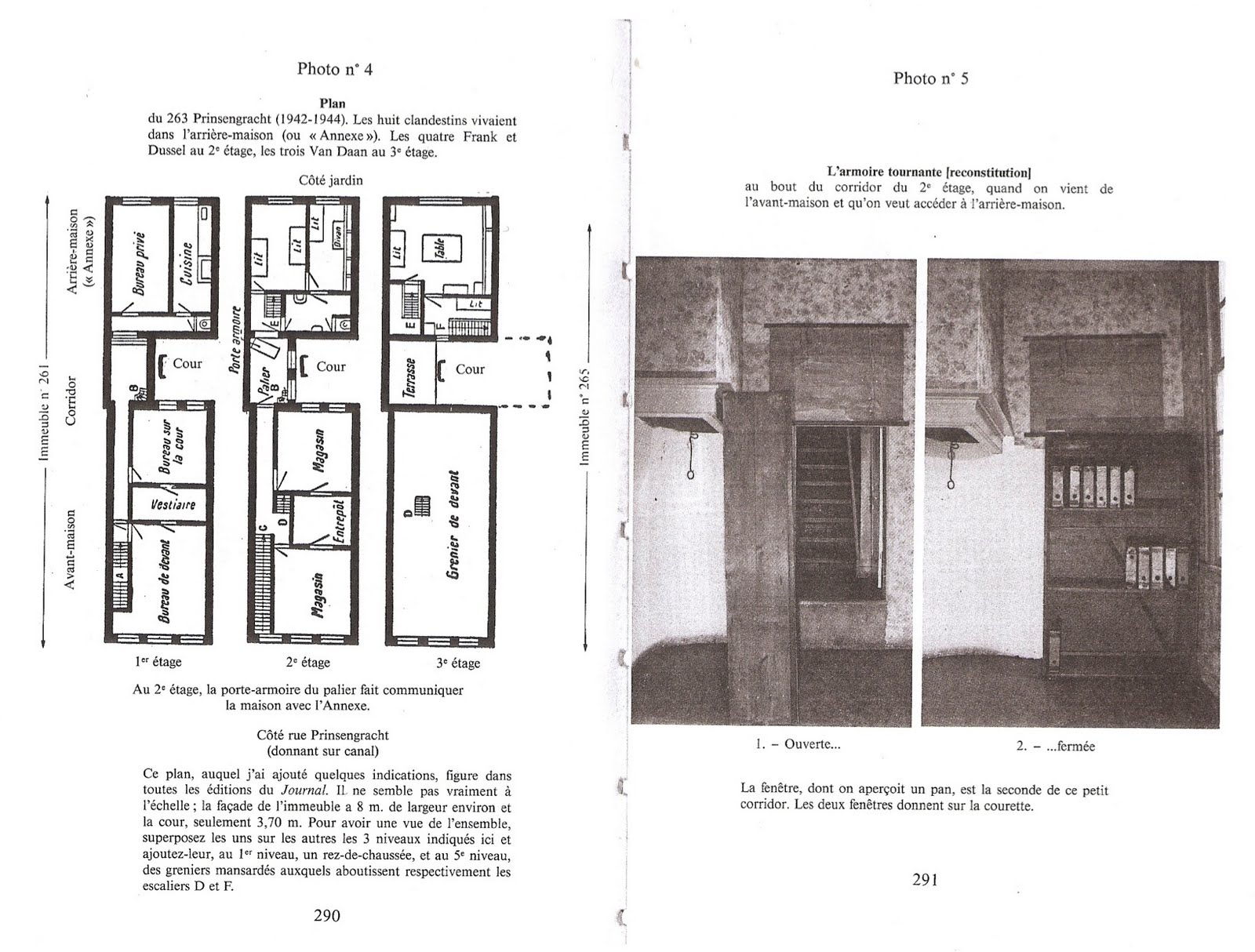

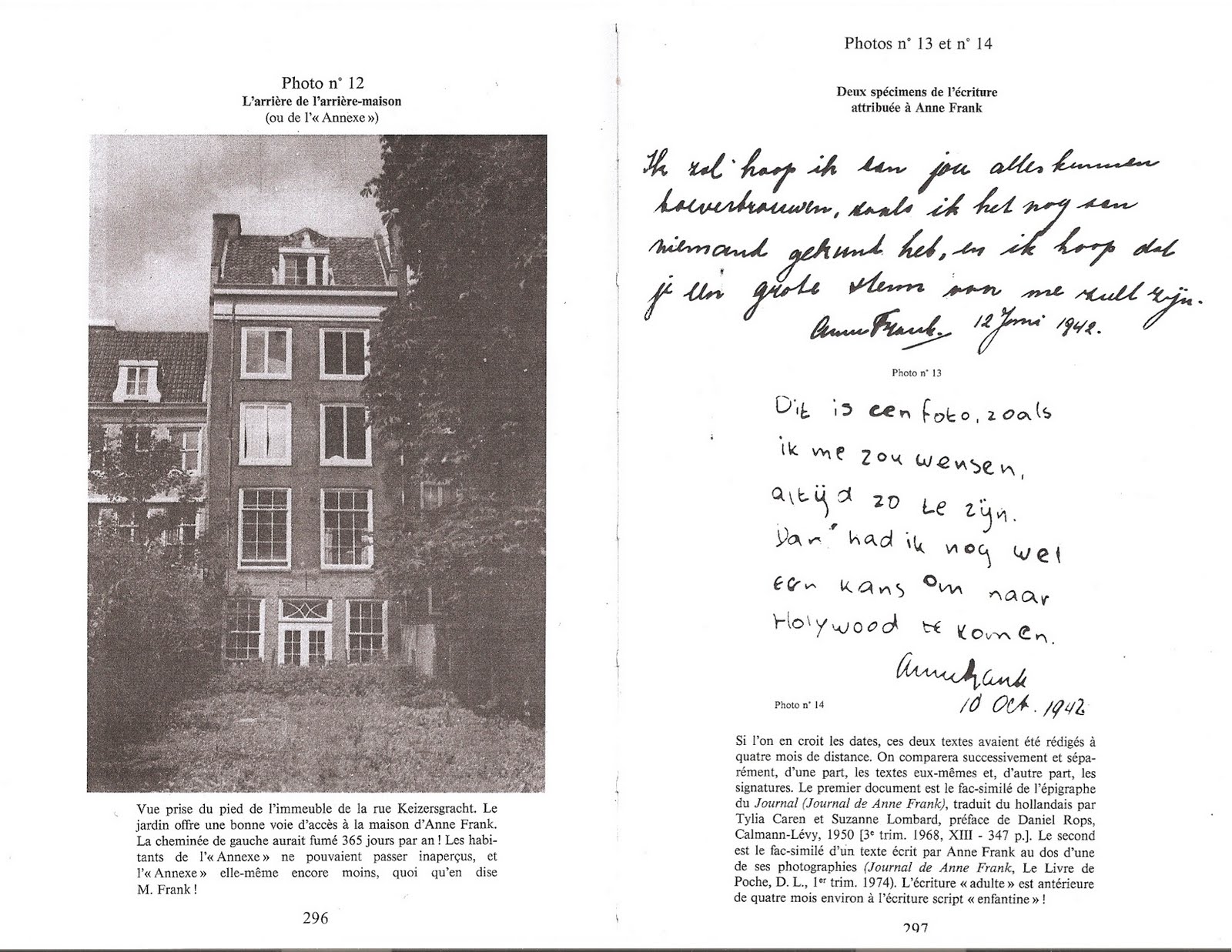

The court in question, despite Mr Rieger’s efforts to relaunch the case, has never handed down a judgment. The German press deplored the fact that Mr Otto Frank was still having to wait for “justice to be done”. Still, this refusal to judge amounts to progress. In a similar case, Professor Faurisson had drawn up a five-page report summarising his research and findings on the “gas chambers”. That statement was signed and the signature legalised. The Professor had gone so far as to cite the text appearing in the French Journal officiel stipulating that a legalisation of signature in France was valid in West Germany. A waste of effort: in its holdings the court ruled that “Faurisson” was only a pseudonym. On the same grounds it rejected the testimony of American professor Arthur R. Butz. Justice is equal for all, subject to the exceptio diabolica.

________________

1) “Is The Diary of Anne Frank” genuine? For two years that question has been included in the syllabus of my seminar of “Critical appraisal of texts and documents”, reserved for degreed students (fourth year).

2) “The Diary of Anne Frank is a fraud”: that is the conclusion from our studies and research, and that is the title of the book I shall publish.

3) In order to study the question posed and find an answer, I have conducted the following investigations:

— [Chapter I] Internal criticism: the Diary’s text itself (in Dutch) contains an inexplicable number of implausible or inconceivable alleged facts (sections 4-12).

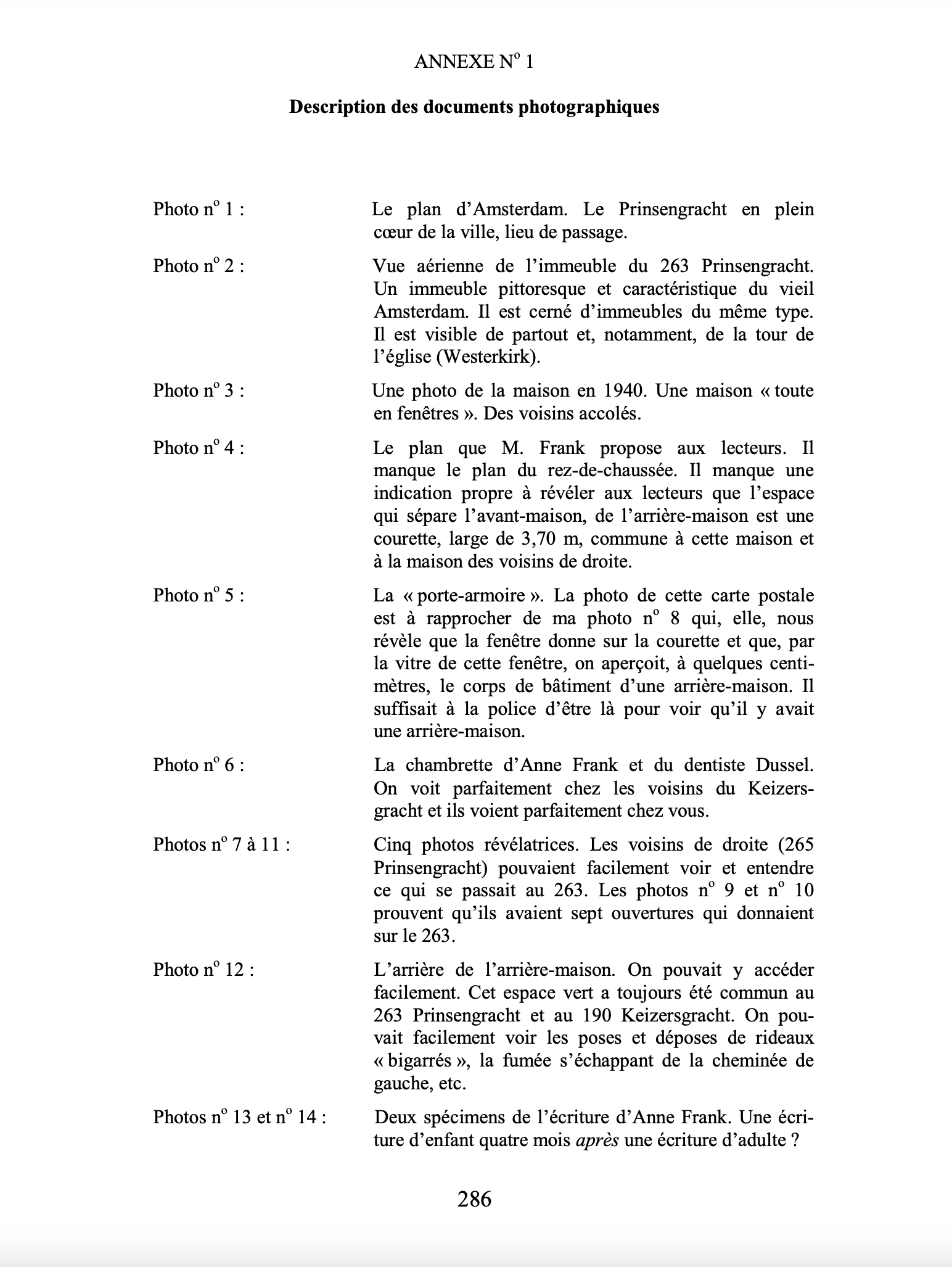

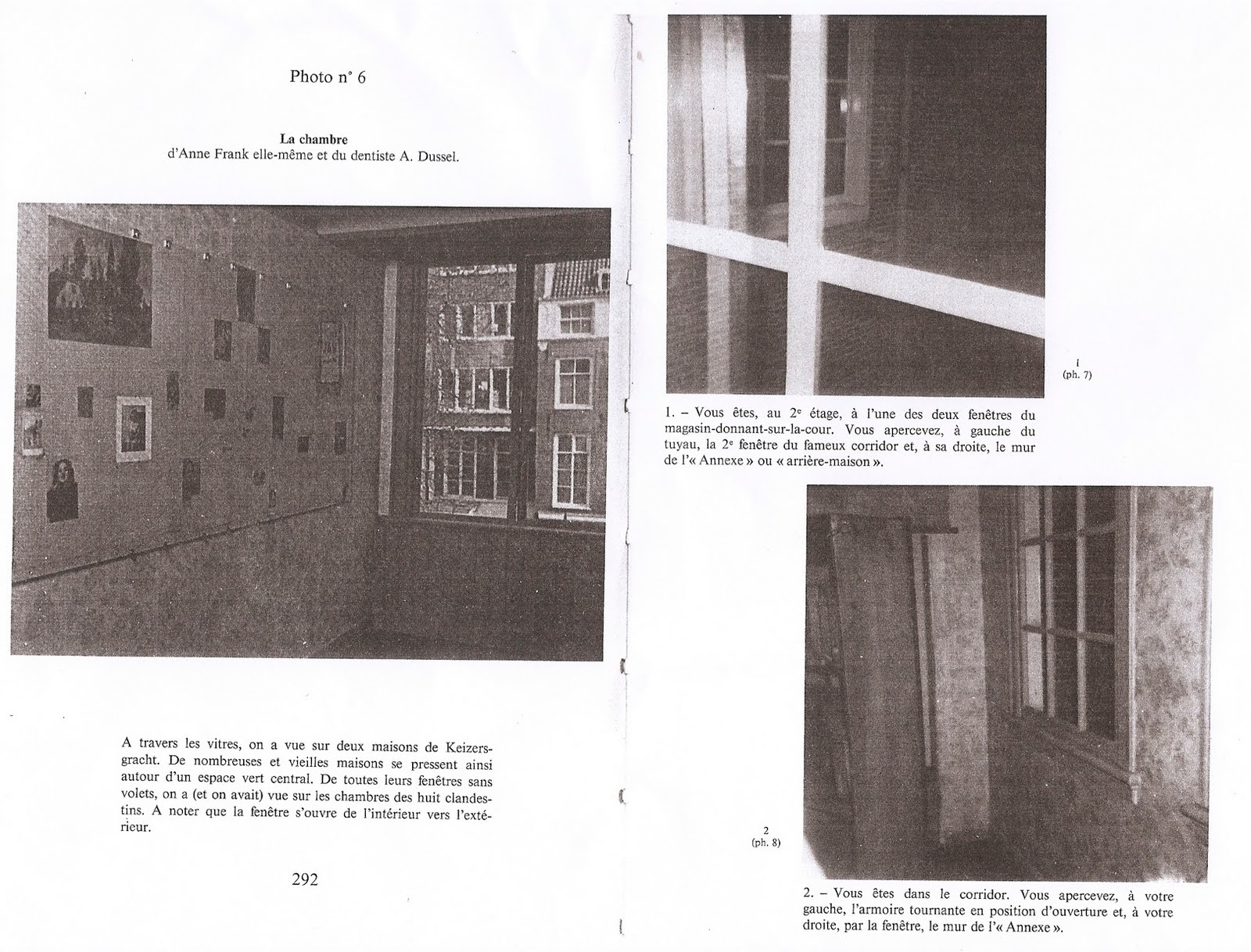

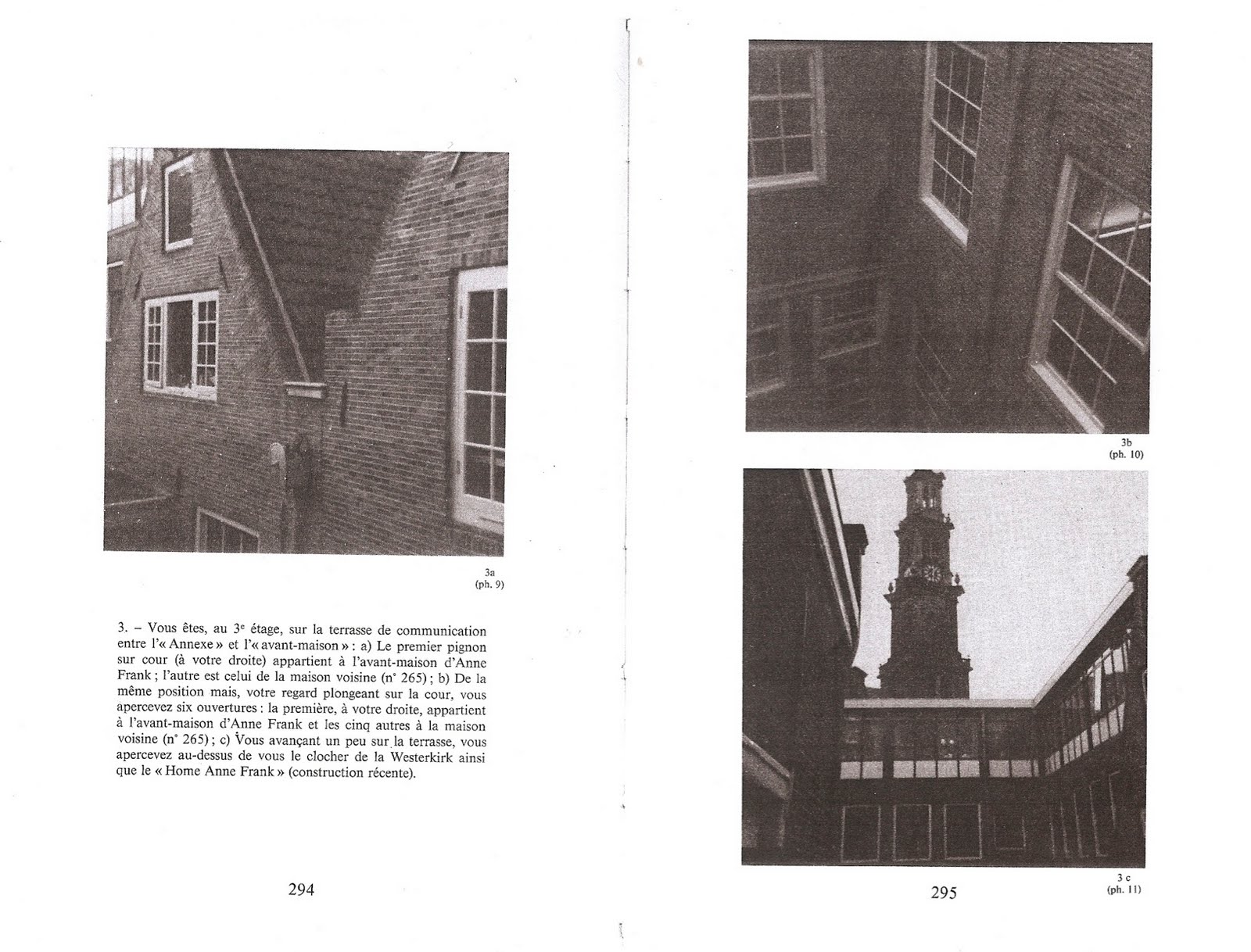

— [Chapter II] Study of the premises in Amsterdam: on the one hand, the physical impossibilities and, on the other, the explanations forged by Anne Frank’s father severely compromise the latter (sections 13-17 with, in appendix 1, photographic documents).

— [Chapter III] Interview with the principal witness: Mr Otto Frank; this interview proved damning for the father of Anne Frank (sections 18-47).

— [Chapter IV] Bibliographical examination: curious silences and revelations (sections 48-55).

— [Chapter V] Return to Amsterdam for a new investigation: the interviews with witnesses proved unfavourable to Mr Frank; the likely truth (sections 56-63).

— [Chapter VI] The two men who, respectively, reported and arrested the Franks: why has Mr Frank wished to assure them such anonymity? (sections 64-71, with appendix 2: “Confidential”).

— [Chapter VII] Comparison between the Dutch and German texts: wanting to do too much, Mr Frank gave himself away; he signed a literary fraud (sections 72-103).

Chapter I

Internal criticism

4) The first step in the investigation is to determine whether the text is consistent within itself. The Diary of Anne Frank proves to contain an inexplicable number of implausible or inconceivable alleged facts.

5) The noises – Let us take the example of the noises. The persons in hiding, we are told, must not make the least noise. This is so much the case that, if they cough, they quickly take codeine. The “enemies” might hear them. The walls are so “thin” (25 March 1943). These “enemies” are very numerous: Lewin, who knows the building “like the back of his hand” (1 October 1942), the men from the shop, the customers, the deliverymen, the postman, the cleaning woman, the night watchman Slagter, the plumbers, the “sanitation service”, the accountant, the police who conduct their house searches, the neighbours both near and far, the owner, etc. It is therefore implausible, even inconceivable that Mrs Van Daan should have been in the habit of using the vacuum cleaner every day at 12:30 pm (5 August 1943). Vacuum cleaners of the era were, moreover, particularly loud. I ask: “How is that conceivable?” My question is not merely formal. It is not oratorical. Its purpose is not to show astonishment. My question is a question. It needs an answer. This question could be followed by forty other questions concerning noises. An explanation is needed, for example, for the use of an alarm clock (4 August 1943). An explanation is needed for the noisy carpentry work: removal of wooden steps, the changing of a door into a pivoting bookcase (21 August 1942), the making of a wooden menorah (7 December 1942). Peter splits wood in the attic before the open window (23 February 1944), work done in order to make, with that wood, “cupboards and other odds and ends” (11 July 1942), and even to build, in the attic,… “a cubbyhole” in which to work (13 July 1943). There is the nearly constant noise of the radio, slammed doors, “endless shouting” (6 December 1943), the arguments, the cries, the yelling, a fracas that “was enough to raise the dead” (9 November 1942). “This was followed by shouts and squeals […]. I was doubled up with laughter” (10 May 1944). The episode related on 2 September 1942 is irreconcilable with the need to be silent and discreet. There we see those in hiding at table. They chatter and laugh. Suddenly, a piercing whistle is heard. And then the voice of Peter who shouts through the stove pipe that he will certainly not be coming down. Mr Van Daan leaps up, “his napkin falling to the floor, and shouted, with the blood rushing to his face, ‘I’ve had enough!’” He goes up to the attic whence one hears “struggling and kicking”. The episode related on 10 December 1942 is of the same kind. There we see Mrs Van Daan being looked after by the dentist Dussel. The latter touches a bad tooth with his probe. Mrs Van Daan then “utter[s] incoherent cries” of pain. She tries to pull the little probe away. The dentist “observed the scene, his hands on his hips, while the rest of us roared with laughter”. Anne, instead of showing the least anxiety in the face of these cries or this mad laughter, declares: “Of course, that was very mean of us. If it’d been me, I’m sure I would have yelled even louder.”

6) The curtains, the refuse, the smoke, the food, etc. – I could repeat the remarks that I make here on the noises in regard to all the realities of material and moral life. The Diary even presents the particularity of not one aspect of the life lived in the house avoiding being either implausible, incoherent or absurd. From the very time of their arrival in the hiding place, the Franks, in order to conceal their presence, install curtains. However, is not installing curtains at windows that, till now, have had none the best way of drawing attention to one’s arrival? Is this not particularly the case if those curtains are made of “scraps of fabric, varying greatly in shape, quality and pattern” (11 July 1942)? In order not to betray their presence, the Franks burn their refuse. But, in doing so, they call attention to their presence with the smoke that escapes from the roof of a supposedly uninhabited house! They make a fire for the first time on 30 October 1942, although they arrived in the place on 6 July. One wonders what they can have done with their refuse of 116 days, mostly of summer. I shall recall, on the other hand, that the food deliveries are huge. In normal diet the persons in hiding and their guests each day consume eight breakfasts, eight to twelve lunches and eight dinners. In nine passages of the book allusion is made to bad, mediocre or insufficient food. Elsewhere the food is abundant and “delicious”. Mr Van Daan “takes a generous portion of whatever he likes” and Dussel “consumes enormous portions” of food (9 August 1943). On the premises they make sausages and salamis, strawberry jam and preserves in jars. Nor do spirits, cognac, wine or cigarettes seem to be lacking. Coffee is so unrare that one fails to understand why the author, enumerating (23 July 1943) what each would want to do on the day he or she was able to leave the hiding place, says that Mrs Frank’s fondest wish would be to have a cup of coffee. On the other hand, on 3 February 1944 – i.e. during the terrible winter of ’43-’44 – here is the inventory of supplies available for those in hiding alone, to the exclusion of any cohabiting friend or “enemy”: 30 kilos of wheat, about 30 kilos of beans and 10 pounds of peas, 50 tins of vegetables, 10 tins of fish, 40 tins of milk, 10 kilos of powdered milk, 3 bottles of salad oil, 4 jars of salted butter, 4 jars of meat, 2 bottles of strawberries, 2 bottles of raspberries, 20 bottles of tomatoes, 10 pounds of oat flakes, 8 pounds of rice. Entering, at other moments, are sacks of vegetables each weighing… 25 kilos, or again a sack of 19 pounds of fresh peas (8 July 1944). The deliveries are made by a “nice greengrocer”, and always “during the lunch hour” (11 April 1944). This is implausible. How, in a city described elsewhere as famished, can a greengrocer leave his shop, in broad daylight, with such loads to leave in a building located in a busy district? How could this greengrocer, in his own district (he was “of the neighbourhood”), avoid meeting his normal customers for whom, in those times of great scarcity, he must normally be a man to be sought out and courted? There are several other mysteries regarding other goods and how they reach the hiding place. For holidays and birthdays, gifts abound: carnations, peonies, narcissi, hyacinths, flower pots, cakes, books, sweets, a cigarette lighter, jewels, shaving kits, a roulette game, etc. In this regard I would point out a real feat of prowess on Elli’s part. She finds the way to make a present of grapes on 23 July 1943. I do indeed say grapes, in Amsterdam, on a 23rd of July. We are even told the price: 5 guilders the kilo.

7) The pivoting bookcase – The invention of the “pivoting bookcase” is an absurdity. Indeed, the part of the building supposed to have housed the persons in hiding existed well before their arrival. Therefore, to install a bookcase is to signal, if not a human presence, at least a change in that part of the building. This transformation of the premises – accompanied by the noise of the carpentry work – could not escape the notice of the “enemies” and, in particular, of the cleaning woman. And this alleged “subterfuge” designed to mislead the police in case of a search, is indeed quite likely, on the contrary, to alert them (“Because so many houses are being searched for hidden bicycles”, writes Anne on 21 August 1942, “Mr Kugler thought it would be better to have a bookcase built in front of the entrance to our hiding place”)? The police, finding no entrance door to the building serving as hiding place, would be surprised by this oddity and would quickly discover that someone had sought to fool them, since they would be standing before a residential building without an entrance!

8) The windows, the electricity, the burglary, etc. – The story is also teeming with implausibilities, inconsistencies, absurdities with regard to the following points: the windows (open and closed), the electricity (on and off), the coal (taken from the common pile without the “enemies’” realising), the openings and closings of the curtains or camouflages, the use of the water and the toilets, the means of doing the cooking, the movements of the cats, the relocations from the front-house to the annex (and vice-versa), the behaviour of the night watchman, etc. The long letter of 11 April 1944 is particularly absurd. It relates a case of burglary. Let it be said in passing that the police are portrayed as stopping before the “pivoting bookcase”, in the middle of the night, under the electric light, in search of burglars who have broken in. They shake the “pivoting bookcase”. These policemen, accompanied by the night watchman, notice nothing and do not attempt to enter the annex! As Anne says later: “God was truly watching over us.”

9) The new owner and the architect – On 27 February 1943 we are told that the new owner has fortunately not insisted on visiting the annex. Koophuis has told him he does not have the key on him and this new owner, although accompanied by an architect, does not examine his new purchase either on this day or any other day.

10) Hiding with one’s family in one’s office – When one has a whole year to choose a hiding place (see 5 July 1942), does one choose one’s office? Does one bring along one’s family? And a colleague? And that colleague’s family? Does one choose a place full of “enemies” that the police and the Germans will automatically come to search should they not find one at home? Those Germans, it is true, are not very inquisitive. On 5 July 1942 (a Sunday) father Frank (unless it is Margot?!) has received a summons from the SS (see the letter of 8 July 1942). This summons will have no follow-up. Margot, sought by the SS, makes her way towards the hiding place by bicycle, and this on 6 July whereas, according to the first of the two letters of 20 June, the Jews had seen their bicycles confiscated some time ago.

11) Too many material absurdities – To dispute the Diary’s authenticity, arguments of a psychological, literary or historical order could be invoked. I shall refrain from doing so here. I shall simply remark that the material absurdities are so grave and so numerous that their repercussion is of a psychological, literary and historical order.

12) Square circles, so to speak – One should not ascribe to the author’s imagination or to the richness of her personality things that are, in reality, inconceivable. Something is inconceivable when “the mind can form no representation of it because the terms that designate it comprise an impossibility or a contradiction, for example: a square circle”. Someone who claims to have seen a square circle, ten square circles, a hundred square circles shows neither a fertile imagination nor a rich personality. For, indeed, what he says and nothing are exactly the same thing. He gives proof of his poverty of imagination. That is all. The absurdities of the Diary are those of a poor imagination developing outside any lived experience. They are worthy of a bad novel or a poor lie. Any personality of the slightest depth contains what are fittingly called psychological, mental or moral contradictions. I shall refrain from demonstrating here that Anne’s personality contains nothing of the sort. Her personality is just as fabricated and implausible as the experience that the Diary is supposed to relate.

From a historical standpoint, I shall not be surprised if a study of Dutch newspapers and English and Dutch radio broadcasts from June 1942 to August 1944 proves the fact of a fraud on the part of the Diary’s real author. On 9 October 1942 Anne already speaks of Jews “being gassed” (Dutch text: vergassing)!

Chapter II

Study of the premises in Amsterdam

13) On the one hand, the material impossibilities and, on the other, the explanations forged by Anne Frank’s father severely compromise the latter.

14) A glass house, accessible from all sides, visible to everyone; live-in neighbours – Someone who has just read the Diary cannot, normally, help but be shocked on discovering the “Anne Frank House”. He discovers a “glass house” that is visible and observable from all around and accessible from its four sides. He also discovers that the floor plan, as reproduced in the book through the efforts of Otto Frank, constitutes a retouching of the reality. Otto Frank had steered clear from drawing the ground floor and from telling us that the little courtyard separating the front house and the annex was only 3.7 metres wide. He had above all avoided pointing out that this same little courtyard was common to the “Anne Frank House” (263 Prinsengracht) and the house standing at the right when one looks at the façade (265 Prinsengracht). Thanks to a whole series of windows and window-doors, the people of 263 and those of 265 lived and moved about under the eyes and under the noses (cooking odours!) of their respective neighbours. The two houses make up one. Besides, the museum today unites the two buildings. What is more, the annex had its own entrance thanks to a door giving on, from the rear, to a garden. This garden is common to 263 Prinsengracht and to the people opposite, living at 190 Keizersgracht. (A person in the museum can see quite distinctly those people of 190 and, besides, those of a good number of other addresses of Keizersgracht.) From this side (the garden side) and from the other side (the canal side) I counted two hundred windows of old houses from which there was a view onto the “Anne Frank House”. Even the residents of 261 Prinsengracht could gain access, by the roof, to 263. It is laughable to suggest the least possibility of a really clandestine life within these spaces. I say this taking into account, of course, the changes made to the premises since the war. I asked ten successive visitors, while showing them the view onto the garden, how Anne Frank had been able to live hidden there with her family for twenty-five months. After a moment of surprise (for people visiting a museum are generally in something of a state of hypnosis), each one of those ten visitors realised, in a few seconds, the total impossibility of it. The reactions were varied: from some, consternation; from others, a burst of laughter (“My God!”). One visitor, doubtless ruffled, said: “Don’t you think it’s better to leave people to their dreams?” No-one supported the case made by the Diary, and this despite some pitiful explanations furnished by the museum’s flyers or inscriptions.

15) Absurd explanations – The explanations are:

- The “enemies” present in one of the rooms of the front house believed that the windows giving onto the little courtyard gave directly onto the garden; they were thus unaware of the very existence of an annex; and, if they were unaware of that, it was because the windows were covered by black paper so as to assure the preservation of the spices stored inside;

- As for the Germans, they had never thought of the existence of an annex, “since they didn’t know this kind of house”;

- The smoke from the stove “did not draw attention since in former times this room (where it was situated) served as a laboratory for the little factory, where a stove had also had to burn every day”.

The first two of these three explanations come from a 36-page publication, without title and without date, printed by Koersen, Amsterdam. The last comes from the four-page flyer available at the museum’s entrance. The content of these two pieces of printed matter has received the endorsement of Mr Otto Frank. However, in all three cases, these explanations have not the least value. The annex was visible and tangible in a hundred ways from the ground floor (forbidden to visitors), the garden, the connecting corridors on four levels, the two windows of the office giving onto the courtyard, the neighbouring buildings. Some of the “enemies” even had to go there to answer the call of nature because there was nothing for that in the front house. The ground floor of the annex even received customers of the business. As for the “little factory” supposed to have existed “in former times”, right in the heart of this residential and commercial district, it is supposed to have, for at least two years, stopped spewing smoke, then, suddenly, on 30 October 1942, to have gone back to spewing smoke. And what smoke! Day and night! Winter and summer, heatwave or not. In the view of all (and, in particular, of “enemies” like Lewin, who used to have his chemist’s laboratory there), the “little factory” is supposed to have resumed operations! But why did Mr Frank strain his wits to find this explanation when, in other parts of the book, the annex is already described as a sort of ghost-house?

16) Mr Frank’s fabrications – In conclusion on this point, I would say that, unless I am wrong in refusing to accord any value to these “explanations”, we are entitled to assert:

- That some facts, very grave for Mr Otto Frank, remain unexplained;

- That Mr Otto Frank is capable of making up stories, even crude and mediocre ones, like those I have pointed out in my critical reading of the Diary. I ask my reader to bear this conclusion in mind; he will see, further on, what answer Mr Frank personally gave me, in the presence of his wife.

17) For the photographic documentation concerning the “Anne Frank House”, see below after the French editor’s postscript (appendix 1).

Chapter III

Interview with the principal witness: Mr Otto Frank

18) This interview, lasting nine hours over two days, proved damning for the father of Anne Frank.

19) I had let Mr Frank know that I was preparing, with my students, a study of the Diary. I had made it clear that my speciality was the “appraisal of texts and documents” and that I needed a lengthy interview. Mr Frank granted me that interview with eagerness, and so it was that I was received at his home in Birsfelden, a suburb of Basel, first on 24 March 1977, from 10:00 am to 1:00 pm, then from 3:00 pm to 6:00 pm and, finally, the next day, from 9:30 am to 12:30 pm. Actually, on the next day the meeting place had been arranged to be a bank in Basel, Mr Frank being keen to remove from a safe deposit box, in my presence, what he called his daughter’s manuscripts. Our interview was therefore conducted that day in part at the bank, in part on the way back to Birsfelden and, in part, once more, at Mr Frank’s house. All the sessions taking place at his house were in the presence of his wife (his second wife, since the first died in deportation – from typhus it seems, as did Margot and Anne). After the first minute of our interview I stated point blank to Mr and Mrs Frank that I had doubts about the Diary’s authenticity. Mr Frank showed no surprise. He declared his readiness to supply me with all the information I might want. I was struck, during those two days, by Mr Frank’s extreme amiability. Despite his age – 88 – he never used the pretext of his weariness to shorten our interview. In the Diary he is described as a man full of charm (see 2 March 1944). He inspires confidence. He knows how to anticipate people’s unexpressed wishes. He adapts to the situation remarkably well. He willingly adopts an argumentation based on feelings. He speaks much of tolerance and understanding. I only once saw him lose his temper, showing himself to be even intransigent and violent: it was with regard to the Zionist cause, which must seem sacred to him. Thus it was that he stated he would never again set foot on French soil because, in his opinion, France is no longer interested in anything but Arab oil, not caring at all about Israel. On only three points did Mr Frank fail to keep his promise to answer my questions. It is interesting to know that those three points are:

- address of Elli, in Holland;

- means by which to find the trace of the shopworker called, in the book, V. M. (and whose name, I knew, was probably Van Maaren);

- means by which to find the Austrian Karl Silberbauer, who had arrested the persons in hiding on 4 August 1944.

20) The witnesses to avoid and the good witnesses, according to Mr Frank – As regards Elli, Mr Frank told me she was quite ill and that, “not very intelligent”, she could be of no help to me. As for the two other witnesses, they had had enough trouble as it was, without my going to pester them with questions that would remind them of a painful past. In contrast, Mr Frank recommended that I get in touch with Kraler (real name: Kugler), who had settled in Canada, and with Miep and her husband, still residing in Amsterdam.

21) Mr Frank admits to having “corrected” and “combined” the texts of “authentic” manuscripts – With regard to the Diary itself, Mr Frank stated that the substance of it was authentic. The events related were true. It was Anne, and Anne alone, who had written the manuscripts of that Diary. Like any literary author, Anne perhaps tended towards either exaggeration or imaginative transformation, but all within ordinary and acceptable limits, the factual truth not suffering. Anne’s manuscripts formed a significant set of writings. What Mr Frank had submitted to the publishers was not the text of those manuscripts, the purely original text, but one that he, in person, had typewritten: a “typescript.” He had been obliged to transform in this way the various manuscripts into a single “typescript” for different reasons. First, the manuscripts presented repetitions. Then, they contained some indiscretions. Then, there were passages of no interest. Lastly, there were… omissions! Mr Frank, noticing my surprise, gave me the following example (doubtless an innocuous example, but were there perhaps graver ones that he was hiding?): Anne liked her uncles very much; however, in her Diary, she had neglected to mention them amongst the people she held dear; so then, Mr Frank repaired that “omission” by mentioning the uncles in the “typescript”. Mr Frank told me he had changed dates! He had also changed the names of individuals. It was Anne herself, it seems, who had doubtless thought of these name changes. She had envisaged the possibility of publication. Mr Frank had found, on a bit of paper, the list of the real names with their false equivalents. Anne apparently even imagined calling the Franks by the name Robin. Mr Frank had cut out of the manuscripts certain specifications of the prices of things. Better: finding himself, at least for certain periods, with two different versions of the text before him, he had had to “combine” (his word) two texts into a single text. Summing up all those transformations, Mr Frank finally told me: “It was a difficult task. I did that task according to my conscience.”

22) The manuscripts: four notebooks, to begin – The manuscripts Mr Frank presented to me as being those of his daughter form an impressive set. I did not have the time to look at them closely. I trusted in the description that was given me and shall summarise it as follows:

– the first date is 12 June 1942; the last is 1 August 1944 (three days before the arrest);

– for the period from 12 June to 5 December 1942 (but this date corresponds to no printed letter) there is a small notebook covered in red, white and brown patterned cloth (the “Scotch notebook”);

– for the period from 6 December 1942 to 21 December 1943 there is no particular notebook (but see, in the following section, the “loose leaf sheets”). This notebook is said to have been lost;

– for the period from 2 December 1942 to 17 April 1944, then for the period from that same date of 17 April (!) to the last letter (1 August 1944), two black, cardboard-bound notebooks in brown paper book covers.

23) Then 338 loose leaf sheets – To these three notebooks and the missing one is added a collection of 338 “loose leaf sheets” for the period from 20 June 1942 to 29 March 1944. Mr Frank says that these sheets constitute a reworking and a reorganising, by Anne herself, of letters contained, in a first form, in the aforementioned notebooks: the “Scotch notebook”, the missing notebook, the first of the two black notebooks.

24) Then a collection of tidied-up Stories – Up to this point the total of what Anne is supposed to have written during her twenty-five months in hiding is, therefore, in five volumes. To that total one should add the collection of the Stories. These Stories are said to have been made up by Anne. The text is presented as a tidying up. This tidying up can only imply, to begin with, editing work on a draft; Anne therefore must have blackened a lot of paper!

25) The handwritings – I have no competence as regards handwriting analysis and thus cannot express an opinion on the subject. I can only give my impressions here. My impressions were that the “Scotch notebook” contained photos, images and drawings as well as a variety of very childish handwritings, whose disorder and fancy appear genuine. One would have to look closely at the handwriting of the texts taken by Mr Frank to form the entire beginning of the Diary. The other notebooks and the whole of the 338 “loose leaf sheets” are in what I would call: an adult handwriting. As for the manuscript of the Stories, it greatly surprised me. One would call it the work of a seasoned chartered accountant and not the work of a child of 14. The table of contents is presented as a register of the Stories with, for each piece, the date of composition, the title and the page number!

26) Two expert analyses in favour of the Diary‘s authenticity – Mr Frank sets great store by the conclusions of the two expert analyses called for, towards 1960, by the Lübeck public prosecutor in the case of a teacher (Lothar Stielau) who, in 1959, had expressed doubts about the Diary‘s authenticity (Case 2js 19/59, VU 10/59). Mr Frank had brought a lawsuit against that teacher. The handwriting analysis had been entrusted to Mrs Minna Becker. Mrs Annemarie Hübner, for her part, had been tasked with telling whether the texts printed in Dutch and in German were faithful to the text of the manuscript. The two expert reports, submitted as evidence in 1961, turned out favourable for Mr Frank.

27) Another expert analysis – But, on the other hand, what Mr Frank did not reveal to me – and what I was to learn well after my visit and through a German contact – is that the prosecutor in Lübeck had decided to have a third analysis made. Why a third analysis? And on what point, given that, to all appearances, the entire field susceptible to investigation was explored by the handwriting expert and by Mrs Hübner? The answer to these questions is as follows: the prosecutor realised that an analysis of the kind made by Mrs Hübner risked finding that Lothar Stielau was, in actual fact, right. In view of the first two analyses, it was going to be impossible to declare that the Diary was dokumentarisch echt (documentarily authentic) (!). Perhaps it could have been declared literarisch echt (literarily authentic) (!). The novelist Friedrich Sieburg would be tasked with answering that curious question.

28) Mrs Hübner – an expert – reports “omissions”, “additions”, “interpolations”, “reorganisings” of the texts; Mr Frank had collaborators – Of those three expert analyses only Mrs Hübner’s would really have been of interest to me. On 20 January 1978 a letter from Mrs Hübner led me to hope I would obtain a copy of her analysis. Shortly afterwards, with Mrs Hübner not answering my letters, I had a German friend telephone her. She had him know that “the matter was very delicate, given that a trial on the question of the Diary was currently under way in Frankfurt”. She added that she had got in touch with Mr Frank. According to the few elements I possess of the content of that analysis, it seems to note a great number of facts that are interesting from the standpoint of a comparison of the texts (manuscripts, “typescript,” Dutch text, German text). Mrs Hübner seems to have mentioned very numerous “omissions” (Auslassungen), “additions” (Zusätze), “interpolations” (Interpolationen). She apparently spoke of a text “revised” for the necessities of publication (überarbeitet). Besides, she seems to have gone so far as to name persons who supposedly gave their “collaboration” (Zusammenarbeit) to Mr Frank in his drafting of the “typescript”. Those persons would be Isa Cauvern and her husband Albert Cauvern. Mrs Anneliese Schütz, for her part, is supposed to have collaborated in establishing the German text, instead of being content with the role of translator.

29) But, says Mrs Hübner, none of this is very serious – Despite these facts that she herself revealed, Mrs Hübner supposedly concluded that the Diary (Dutch printed text and German printed text) was genuine. Thus she seems to have expressed the following opinion: “These facts are not serious.” That judgment can only be her personal one. There is the whole matter. Who assures us that another judgment entirely could not be pronounced on the facts pointed out by the expert? And then, to begin, has the expert shown impartiality and a really scientific spirit in calling the facts as she has called them? What she has called, for example, “interpolations” (a word scientific in appearance and ambiguous in scope) would others not call “retouchings”, “reworkings”, “intercalations” (words doubtless more exact, and more precise)? In the same manner, words like “additions” and, especially, “omissions” are neutral in appearance but, in actual fact, cover confused realities: an “addition” or an “omission” may be honest or dishonest; it may change nothing important in a text or it can, to the contrary, alter it profoundly. In the particular case at hand, these two words have a frankly benign appearance!

30) The case brought by Mr Frank against the teacher Lothar Stielau never went to court – In any event those three expert analyses (Becker, Hübner and Sieburg) cannot possibly be deemed to have probative value, since they were not examined in court. Indeed, for reasons I do not know, Mr Frank was to drop his suit against Lothar Stielau. If my information is accurate, the latter agreed to pay 1,000 DM of the costs incurred of 15,712 DM. I suppose Mr Frank paid the court of Lübeck that 1,000 DM and added to that sum 14,712 DM of his own. I believe I recall Mr Frank’s telling me that Lothar Stielau had, moreover, agreed to offer him his written apology. Lothar Stielau, at the same time, had lost his teaching job. Mr Frank did not talk to me about Lothar Stielau’s co-defendant: Heinrich Buddeberg. Perhaps that man too had to pay 1,000 DM and offer an apology.

31) Mr Frank proved incapable of explaining the mass of material impossibilities – I dwell here on these matters of analyses only because, in our interview, Mr Frank had himself dwelt on them, whilst not mentioning certain important facts (for example, the existence of a third analysis), and whilst presenting me the two analyses as conclusive. The matter of the manuscripts did not interest me very much either. I knew I would not have the time to examine them closely. What interested me most of all was to know how Mr Frank would explain the “inexplicable quantity of implausible or inconceivable facts” that I had noted in reading the Diary. After all, what did I care whether manuscripts, even declared authentic by experts, contained that kind of facts if those facts could not be real? However, Mr Frank was to prove incapable of giving me the least explanation. In my view, he was expecting to see the authenticity of the Diary disputed by the usual arguments of a psychological, literary or historical order. He was not expecting arguments of internal criticism addressing the realities of material life: the realities which, as one knows, are “stubborn”. In a moment of disarray Mr Frank, moreover, was to tell me: “But… I never thought about those material matters!”

32) Through pure internal criticism, I detect a material anomaly and a textual anomaly – Before coming to precise examples of that disarray, I owe it to the truth to say that twice Mr Frank was to give me a good answer, and this concerning two episodes I have not mentioned hitherto, precisely because they were to find an explanation. The first episode had been incomprehensible because of a small omission in the French translation (at the time I did not possess the Dutch text). As for the second episode, it had been incomprehensible due to an error present in all the printed texts of the Diary. Where, at the date of 8 July 1944, there is a male greengrocer, the manuscript has: “la marchande de légumes” (the female greengrocer). And this is fortunate, for an attentive reader of the book knows quite well that the greengrocer in question cannot have delivered to those in hiding “19 pounds of green peas” (!) on 8 July 1944 for the good reason that he was arrested by the Germans 45 days before on the most serious of grounds (“He was hiding two Jews in his house”). This had put him “on the edge of an abyss” (25 May 1944). It was hard to conceive how a greengrocer leapt from “the abyss” in order to deliver to other Jews such a compromising quantity of goods. To tell the truth, it is hardly more conceivable on the part of the unfortunate man’s wife but the fact is there: the text of the manuscript is not absurd like the Dutch, French, German, and English printed texts… The manuscript had been drafted more carefully. The possibility remains that the error of the printed texts was perhaps not an error, but indeed a deliberate and misguided correction of the manuscript. In effect, the printed Dutch text reads: “[…] van der groenteboer om de hoek, 19 pond” [shouts Margot]; and Anne replies: “Dat is aarding van hem.” In other words, Margot and Anne use the masculine form twice: “from the local [male] greengrocer, 19 pounds”. Anne’s reply: “That’s nice of him.” For my part, I would draw two other conclusions from this episode:

- Internal criticism bearing on a text’s consistency makes it possible to detect anomalies that prove to be true anomalies;

- A reader of the Diary, having come to this episode of 8 July 1944, would be entitled to declare that a book in which one of the heroes (“the nice local greengrocer”) rises from the depths of the abyss as one resuscitates from death is absurd.

33) The greengrocer aided eight persons without knowing it – That greengrocer, Mr Frank told me, was called Van der Hoeven. Deported for having sheltered Jews in his house, he returned from deportation. During commemorative ceremonies he has sometimes appeared beside Mr Frank. I asked Mr Frank whether, after the war, people of the neighbourhood had said to him: “We suspected there were people hiding at 263 Prinsengracht.” Mr Frank answered explicitly that no-one had suspected their presence – not the men of the shop, not Lewin, not Van der Hoeven. The last had presumedly helped them without knowing it!

34) Mrs Frank’s reaction of good sense on hearing an “explanation” of Mr Frank’s – Despite my repeated questions on the point, Mr Frank was unable to tell me what his neighbours at no. 261 sold or made. He did not remember that there had been in his own house, at no. 263, a cleaning woman described in the book as a potential “enemy”! He ended up answering that she was “very, very old” and that she came only quite rarely, perhaps once a week. I said that she must have been astonished on suddenly seeing the installation of the “pivoting bookcase” on the second floor landing. He replied no, given that the cleaning woman never came by there. This answer was to cause, for the first time, something of an altercation between Mr Frank and his wife, also present at our interview. Before this, in effect, I had taken the precaution of having Mr Frank specify that the persons in hiding had never done any housekeeping apart from cleaning a part of the annex. The logical conclusion of his two statements thus became: “For twenty-five months, no-one did any cleaning of the second floor landing.” Grasping this implausibility, Mrs Frank abruptly intervened to say to her husband: “Come on! No cleaning on that landing! In a factory! But there would have been dust this high!” What Mrs Frank might have added is that that landing was supposed to serve as a passageway for those in hiding in their comings and goings between the annex and the front house. The trail of their goings and comings would have been obvious amidst so much accumulated dust. And this with no account taken of the dust from the coal carried up from below. In fact, Mr Frank could not be telling the truth when, in so speaking, he was talking about a sort of ghost of a cleaning woman for so big and dirty a house.

35) Several other reactions of good sense and a conclusion of good sense – Several times, at the beginning of our interview, Mr Frank attempted in that way to supply explanations which, in the end, explained nothing at all and, instead, led him into impasses. I must say here that his wife’s presence would prove particularly useful. Mrs Frank, who was pretty well acquainted with the Diary, manifestly believed up to then in both the Diary‘s authenticity and her husband’s sincerity. Her surprise was only the more striking on realising the execrable quality of his answers to my questions. For my part, I retain a painful memory of what I would call certain “realisations” by Mrs Frank. I do not at all wish to say that Mrs Frank today takes her husband for a liar. But I do maintain that Mrs Frank was keenly aware, during our interview, of the anomalies and severe absurdities of the whole Anne Frank story. On hearing her husband’s “explanations” she happened to utter, in his regard, such phrases and sentences as:

“Come on!”

“What you’re saying is unbelievable!”

“A vacuum cleaner! That’s unbelievable! I’d never noticed it!”

“But you were really reckless!”

“That, really – that was reckless!”

Mrs Frank’s most interesting remark was: “I’m sure the people [in the vicinity] knew you were there.” For my part, I would say rather: “I’m sure the people in the vicinity saw, heard, smelled the presence of the persons in hiding, if indeed there were persons hiding in that house for twenty-five months.”

36) Mr Frank’s explanations, then silence – I would take one other example of Mr Frank’s explanations. According to him, the people who worked in the front house could not see the body of the annex building because of the “masking paper on the window panes”. This statement, which is found in the museum’s booklets, was repeated to me by Mr Frank before his wife. Without dwelling on it, I went on to another subject: that of electricity consumption. I pointed out that use of electricity in the house had to be considerable. Mr Frank being surprised at my remark, I specified: “It had to be considerable because the lights were on all day in the office on the courtyard and in the shop on the front house courtyard.” Mr Frank then said: “How do you mean? Electric lighting isn’t needed in broad daylight!” I remarked that those indoor spaces could not receive the daylight, given that the windows had “masking paper” over them. He then replied that the spaces were, nonetheless, not in the dark: a disconcerting reply, one in contradiction with the statement in the booklet written by Mr Frank: “Spices must be kept in the dark” (page 27 of the aforementioned 36-page booklet). Mr Frank then presumed to add that, anyhow, all that could be made out through the windows on the courtyard was a wall. He specified, contrary to the obvious, that it could not be seen that it was the wall of a house! A specification contradicting the following passage in the same booklet: “therefore, although you saw [obscured] windows, you could not see through them, and everyone took it for granted that they gave onto the garden” (ibidem). I asked whether those obscured windows were, nonetheless, sometimes open, if only for airing out the office where visitors were received, if only in the summer, on torrid days. Mrs Frank agreed with me there, remarking that those windows had, all the same, to be open sometimes. Silence from Mr Frank.

37) Other silences – The list of noises left Mr and, especially, Mrs Frank perplexed. As regards the vacuum cleaner, Mr Frank started, saying to me: “But there couldn’t be a vacuum cleaner.” Then, upon my assurance that there had been one, he began to stutter. He told me that, if there was really a vacuum cleaner, they must have used it in the evening, when the employees (the “enemies”) had left the front house after work. I objected that the noise of a vacuum cleaner of that era would have been heard by the neighbours all the better (the walls were “thin” – 25 March 1943) as it would have been made in empty spaces or in the proximity of empty spaces. I revealed to him that, in any case, Mrs Van Daan, for her part, was supposed to have used the vacuum cleaner every day, regularly, at around 12:30 pm (the window likely being open). Silence from Mr Frank, whereas Mrs Frank was visibly moved. Same silence for the alarm clock, sometimes ringing at the wrong hour (4 August 1943). Same silence for the removal of the ashes, above all on hot days. Same silence about those in hiding helping themselves from the store of coal (a precious commodity), common to the whole house. Same silence on the matter of the bicycles used after their confiscation and after Jews had been forbidden to use them.

38) A number of questions thus remained unanswered or else, at first, gave rise to explanations by which Mr Frank aggravated his case. Then Mr Frank had, as it were, a brainwave: a magic formula. That formula was as follows: “Mr Faurisson, you are theoretically and scientifically right. I agree with you 100%…. What you point out to me was, in effect, impossible. But, in practice, that was still the way things happened.” I let him know that his statement bewildered me. I told him it was a bit as though he agreed with me that a door could not be at-the-same-time-open-and-closed and as though, despite this, he were telling me he had seen such a door. I pointed out, besides, that the words “scientifically” and “theoretically” and “in practice” were unnecessary and introduced a distinction devoid of meaning for, in any case, regardless of whether it were “theoretical,” “scientific” or “practical”, a door at-the-same-time-open-and-closed quite simply could not exist. I added that I would prefer, for each particular question, an appropriate response or, should he prefer, no answer at all.

39) The “explanations” given to visitors in Amsterdam are worthless: they are for tourists – Towards the start of our interview Mr Frank had made, in the friendliest way in the world, a capital concession, a concession announced by me in section 16 above. As I was beginning to have him understand that I found the explanations he had supplied in his booklets absurd, as concerned both the Germans’ ignorance of the typical architecture of Dutch houses and the constant presence of smoke above the annex (the “little factory”), he wanted to admit right away, without any insistence on my part, that it was a matter there of pure inventions of his. Without using, it is true, the word inventions, he stated, in substance: “You’re completely right. In the explanations given to visitors, one has to simplify. That’s not so serious. It has to be made agreeable for the visitors. It’s not the scientific way. One isn’t always fortunate enough to be able to be scientific.”

40) Inventions that the public will like – That remark in confidence enlightens us on what I believe to be a character trait of Mr Frank: he has the sense of what the public like and seeks to adapt himself accordingly, even if it means taking liberties with the truth. Mr Frank is not a man to worry himself overmuch. He knows that the general public are content with little. The public seek a sort of comfort, dream, easy world where they will be served exactly the kind of emotion that strengthens them in their habits of feeling, seeing and reasoning. That smoke above the roof might unsettle the public? No problem! Let’s invent an explanation not necessarily plausible, but simple and, if need be, simple and crude. Perfection is attained if that invention panders to conventional wisdom or habitual sentiments: for instance, it is quite likely that for those who love Anne Frank and come to visit her house, the Germans are brutes and beasts; well, they will find a confirmation of that in Mr Frank’s explanations: the Germans went so for as to be ignorant of the architecture typical of Amsterdam houses (sic!). In a general way, Mr Frank appeared to me, more than once, as a man utterly lacking in finesse (but not in trickery) and for whom a literary work is, compared with reality, a form of lying invention, a domain where one takes liberties with the truth, a thing that “is not so serious” and makes it possible to write practically anything.

41) The “anomalies” of the floor plan. Mr Frank concedes that the bookcase was pointless – I asked Mr Frank what explanations he could offer on the two points where he concurred that he told visitors nothing of consequence. He was unable to answer. I questioned him on the layout of the premises. I had noted anomalies in the house’s floor plan such as it is reproduced by Mr Frank – in all the editions of the Diary. Those anomalies had been confirmed for me by my visit to the museum (with account taken of the changes made to the premises in order to make a museum of them). It was then that, once again, Mr Frank, faced with the obvious physical reality, was led to make some new and weighty concessions to me, particularly, as will be seen, with regard to the “pivoting bookcase”. He began by admitting that the floor plan diagram should not have concealed the fact that the small courtyard separating the front house from the annex was common to no. 263 (the Frank house) and to no. 265 (the house of their neighbours and “enemies”); besides, it is bizarre that, in the Diary, there was not the slightest allusion to this fact which, for the persons in hiding, was of extreme gravity. Mr Frank then acknowledged that the diagram suggested that on the third floor the open air passageway was not accessible; however, that passageway was accessible by a door from the annex and it could quite well have offered either the police or the “enemies” an easy access to the very heart of the premises where the fugitives dwelt. Lastly and above all, Mr Frank conceded that the “pivoting bookcase”… made no sense. He acknowledged that this cosmetic change could by no means have prevented a search of the annex, since the annex was accessible by other ways and, notably, by the most natural way: the entrance door giving onto the garden. This obvious fact, it is true, will not appear to someone viewing the diagram, for the diagram includes no drawing of any part of the ground floor. As for the museum visitors, they do not have access to that ground floor. That famous “bookcase” thus becomes a particularly aberrant invention of “the fugitives”. One must, in effect, imagine here that the making of that “bookcase” was a perilous job. The destruction of the stair steps, the assembling of that false bookcase, the transforming of a passageway into an apparent dead end, all that could only arouse the “enemies’” suspicions. All that had therefore been suggested by Kraler and executed by Vossen (21 August 1942)!

42) Had the fugitives nothing to fear? – The more my interview went on, the more Mr Frank’s embarrassment became visible. But his amiability did not wane; to the contrary. Towards the end Mr Frank was to use a sentimental line of argument, apparently clever and in a good natured tone. That line was the following: “Yes, I grant you that, we were a bit reckless. Certain things were a little dangerous, it must be acknowledged. Besides, that’s perhaps the reason why we were finally arrested. But don’t think, Mr Faurisson, that the people were suspicious to that extent.” This curious line of argument would lead him to make such remarks as: “The people were kind!” or: “The Dutch were good!”, or even, on two occasions: “The police were good!”

43) … or everything to fear? – These remarks had but one disadvantage: they rendered all the “precautions” pointed out in the book absurd. To some degree, they even stripped the book of all its sense. That book recounts, in effect, the tragic adventure of eight persons who are hunted, forced to hide, to bury themselves alive for twenty-five months in the midst of a ferociously hostile world. In those “days in the tomb” only a few elite beings knew of their existence and brought them help. It may be said that in resorting to his last arguments Mr Frank was attempting, with one hand, to stop up the cracks in a work that, with the other hand, he was dismantling.

44) A curious revelation of Schnabel’s book – On the evening of our first day of interviews, Mr Frank handed me his own copy, in French, of the book by Ernst Schnabel, Spur eines Kindes (French title: Sur les traces d’Anne Frank; English title: Anne Frank: A Portrait in Courage). He told me I might find in it answers to some of my questions. The pages of that copy had not been separated. It must be mentioned that Mr Frank speaks and understands French but reads it with a little difficulty. (I specify here that all our interviews took place in English, a language that Mr Frank masters perfectly.) I had not yet read that book, because strict observance of the methods proper to pure internal criticism entails an obligation to read nothing about a work so long as one has not yet personally got a clear idea of it. During the night preceding our second interview I browsed through the book. Amongst the ten or so points that would confirm for me that the Diary was a pure fabrication (and this notwithstanding Schnabel’s many efforts to persuade us of the contrary), I noted, on page 151, an astounding passage. This passage concerned Mr Vossen, the man who, it seems, had devoted his energies as a carpenter for the making of the “pivoting bookcase” meant to conceal the hiding place (Diary, 21 August 1942). The “good Vossen” was supposed to work at 263 Prinsengracht. He used to keep the fugitives informed on everything that happened in the shop. But illness now obliged him to stay at home, where his daughter Elli joined him after working hours. On 15 June 1943 Anne speaks of him as a dear friend. However, according to a remark of Elli reported by Schnabel, the good Vossen… was unaware of the Franks’ existence at 263 Prinsengracht! Elli recounts, in fact, that on 4 August 1944, when arriving home, she informed her father of the Franks’ arrest. “I sat on the edge of the bed and told him everything. My father liked Mr Frank very much, had known him for a long time. He was unaware that the Franks had not left for Switzerland, as was claimed, but had gone into hiding on the Prinsengracht.” But what is incomprehensible is that Vossen could have believed that rumour. For nearly a year he had been able to see the Franks at Prinsengracht, to speak with them, help them, befriend them. Then when, owing to bad health, he had quit his job on the Prinsengracht, his daughter Elli was able to keep him informed of the doings of his friends, the Franks.

45) This revelation does not appear in the German or American version – Mr Frank could not explain that passage from Schnabel’s book. Rushing to consult the German and the English texts of the book, he made a surprising discovery: the whole passage where Elli spoke with her father did indeed appear in those texts, but… without the sentence beginning “He was unaware” and ending with “the Prinsengracht”. In the French text, Elli continued: “II ne dit rien. Il restait couché en silence.” For comparison, here is the German text:

Ich setze mich zu ihm ans Bett und habe ihm alles gesagt. Er hing sehr an Herrn Frank, denn er kannte ihn lange [passage missing]. Gesagt hat er nichts. Er hat nur dagelegen. (Anne Frank/Ein Bericht von Ernst Schnabel, Spur eines Kindes, Fischer Bucherei, 1958, 168 pages, page 115.)

And here, the English text:

I sat down beside his bed and told him everything. He was deeply attached to Mr Frank, who he had known a long time [passage missing]. He said nothing. (Anne Frank: A Portrait in Courage, Ernst Schnabel, Translated from the German by Richard and Clara Winston. Harbrace Paperback Library, Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., New York 1958; 181 pages; page 132.)

46) A bibliographical curiosity – Once back in France, it was easy for me to clear up this mystery: from many other points in the French text it became evident that there had existed two original German versions. Schnabel’s first version must have been sent in “typescript” to the Paris publishing house Albin Michel to enable a translation into French without losing too much time. Thereupon Schnabel or, most likely, Mr Frank, had proceeded with a revision of his text. He had then eliminated the contentious sentence about Vossen. Then Fischer published that corrected version. But, in France, efforts had been redoubled and the book was already coming off the presses. It was too late to correct it. I note, moreover, a bibliographical curiosity: my copy of Sur les traces d’Anne Frank (translated from the German by Marthe Metzger, Albin Michel, 1958, 205 pages) bears the mention “18th thousand” and its printing date was February 1958. However, the first thousand of the original German edition is from März 1958. Thus the translation did indeed appear before the original.

47) My relations with Mr Frank deteriorate – It remains, of course, to be known why Ernst Schnabel or Mr Frank had seen fit to make that astonishing correction. Nonetheless Mr Frank showed his disarray once again before this further anomaly. We took leave of each other in a most painful atmosphere, where each sign of friendliness shown by Mr Frank made me a bit more uneasy. Shortly after my return to France I wrote to thank him for his hospitality and to ask for Elli’s address. He replied amiably, asking me to send him back the copy of Schnabel’s book in French and saying nothing about Elli. I sent him back his copy, asking again for the address. No reply this time. I telephoned him at Birsfelden. He replied that he would not give me that address, all the less as I had sent Kraler (Kugler) an “idiotic” letter. I shall return to that letter.

Chapter IV

48) Bibliographical examination: Curious silences and revelations.

49) Schnabel’s book and the article in Der Spiegel – The aforementioned book by Schnabel (Anne Frank: A Portrait in Courage) has some curious omissions, whilst the long article, unsigned, that Der Spiegel devoted to the Diary in the wake of the Stielau case (1 April 1959, pages 51-55), brings us some curious revelations. The title is eloquent: “Anne Frank. Was Schrieb das Kind?” (Anne Frank. What did the child write?)

50) Not one of the forty-two “witness” wished to talk about the Diary – Ernst Schnabel openly defends Anne Frank and Otto Frank. His book is relatively rich on all that precedes and on all that follows the twenty-five months of their life at Prinsengracht. In contrast, it is extremely poor concerning those twenty-five months. One would say that the direct witnesses (Miep, Elli, Kraler, Koophuis, Henk) have nothing to declare on that period of capital importance. Why do they stay silent? Why have they said only a few banal things like “[…] when we had our plate of soup upstairs with them at noon” (page 114) or “We always had lunch together” (page 117)? Not one concrete detail, not one description, not one anecdote is there that, by its precision, would give the impression that the persons in hiding and their faithful friends regularly shared the same table at noon. Everything appears in a kind of fog. However, those witnesses were questioned only thirteen years, at the most, after the Franks’ arrest, and some of them, such as Elli, Miep and Henk, were still young. I am not talking about numerous other persons whom Schnabel wrongly calls “witnesses” but who, in fact, had never known or even met the Franks. This is the case, for example, with the famous “greengrocer” (Gemüsemann). “He did not know the Franks at all” (page 82). In a general way, the impression I get from Schnabel’s book is as follows: this Anne Frank really existed; she was a little young girl without great character, without strong personality, not precocious at school (the contrary even) and in whom no-one suspected any aptitude for writing; that unfortunate child experienced the war’s horrors; she was arrested by the Germans; she was interned, then deported; she went through the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp; she was separated from her father; her mother died in the Birkenau infirmary on 6 January 1945; she and her sister, in or about October 1944, were transferred to Bergen-Belsen; Margot died of typhus; then, in her turn, Anne, alone in the world, was also to die of typhus in March of 1945. There we have points about which the witnesses did not hesitate to talk. But with all of them one senses mistrust before an Anne of legend, able to take up the pen, as we are told, to keep that Diary and write those Stories, and to draft “a beginning of a novel”, etc. Schnabel himself writes, revealingly: “My witnesses had a good deal to say about Anne as a person; they took account of the legend only with great reticence, or tacitly ignoring it. Although they did not take issue with it by so much as a word, I had the impression they were checking themselves. All of them read Anne’s diary; they did not mention it” (pages 4-5). That last sentence is important: “All of them had read Anne’s diary; they did not mention it.” Even Kraler, who from Toronto sent a long letter to Schnabel, made no mention either of the Diary or of Anne’s other writings (page 87). Kraler is the only direct witness to tell an anecdote or two about Anne; however, in a very curious way, he places these anecdotes in the period where the Franks still lived in their apartment on Merwedeplein, before their “disappearance” (“before they went into hiding”, page 87). It is only in the corrected edition that the second anecdote is placed at Prinsengracht, even “when they were in the secret annex” (page 88). The witnesses did not want their names to be published. The two most important witnesses (the “probable betrayer” and the Austrian policeman) were neither questioned nor even sought. Schnabel makes several attempts to explain this odd avoidance (pages 8, 139 and all of the end of chapter ten). He goes so far as to present a sort of defence of the arresting policeman! One person [Mrs Kuperus] nevertheless does, all the same, mention the Diary, but this is to draw attention to a point that seems bizarre to her, concerning the Montessori school where she was headmistress (page 40). Schnabel himself deals with the Diary oddly. How to explain, in effect, the cuts he makes when citing a passage like that on his page 123? Giving a long excerpt from the letter of 11 April 1944 in which Anne recounts the police raid in the wake of the burglary, he leaves out the sentence where Anne states the main reason for her anxiety: it is that the police, it seems, went so far as to give the “bookcase” some loud jolts. (“This, and when the police rattled the bookcase door, were my worst moments.”) Would Schnabel not have thought, like any man of sense, that that passage was absurd? In any event, he tells us he visited 263 Prinsengracht before its transformation into a museum. He did not see any “pivoting bookcase” there. He writes: “The bookcase that was built against the door to disguise it has been pulled down. Nothing is left but the twisted hinges hanging beside the door.” (page 74) He found no trace of any special camouflage but only, in Anne’s room, a yellowed piece of curtain (“A tattered, yellowed remnant of curtain still hangs at the window” (page 75). Mr Frank, it seems, marked in pencil on the wallpaper, near a door, the successive heights of his daughters. Today, at the museum, visitors can see an impeccable square of wallpaper, kept under glass, where the perfectly preserved pencil marks, which appear to have been made the same day, may be noted. We are told that these pencil marks indicated the heights of Mr Frank’s children. When I saw Mr Frank at Birsfelden I asked him whether this was not a “reconstitution”. He assured me it was all authentic. This is hard to believe. Schnabel, for his part, simply saw, as a mark, an “A 42” which he interprets as “Anne 1942”. What is curious is that the museum’s “authentic” paper bears nothing of the kind. Schnabel does say that he saw only that mark and that the others were destroyed or torn off (“the other marks have been stripped off” [ibidem].) Might Mr Frank have rendered himself guilty here of a trick (ein Trick), like the one he suggested to Henk and Miep for the photocopy of their passport?

A very interesting point about Anne’s story is that concerning the manuscripts. I regret to say that I find the account of their discovery, and then of their passing on to Mr Frank by his secretary Miep, implausible. The police are said to have scattered all sorts of papers on the floor. Amongst those papers, Miep and Elli are said to have gathered up a “Scotch notebook” (ein rotkariertes Buch; a red plaid book) and a number of other papers on which they recognised Anne’s handwriting. They supposedly read none of these. They are supposed to have put all these papers away in the big desk. Then, these papers were allegedly handed over to Mr Frank on his return from Poland (pages 179-181). This account does not square at all with the account of the arrest. The arrest was made slowly, methodically, correctly, just like the search. The testimonies are unanimous on this point (see Chapter IX). After the arrest the policeman returned to the premises several times. He questioned Miep in particular. The police wanted to know whether the Franks were in contact with other persons in hiding. The Diary, such as we know it, would have revealed, at a brief glance, a load of information of great value to the police and terribly compromising for Miep, Elli and all the friends of the fugitives. The police may have disregarded the “Scotch notebook” if, in its original state, it contained, as I think, only some drawings, photographs or notes of an innocuous nature. But it would seem implausible for them to leave several notebooks and several hundred scattered sheets on which the writing was, at least in appearance, that of an adult. As for Elli and Miep, it would have been madness on their part to gather together and keep, especially in the desk, such a mass of compromising documents. They knew, it seems, that Anne was keeping a diary. A diarist is supposed to recount what happens day to day. Consequently there was a risk that Anne mentioned Miep and Elli in them.

51) The Dutch know only a very belated, and heavily cut, edition of Spur eines Kindes [Anne Frank: A Portrait in Courage] – On the subject of Schnabel’s book, Mr Frank had made a surprising revelation. He had told me that the book, although translated into several languages, had not been translated into Dutch! The reason for this exception was that the principal witnesses lived in Holland and, out of both modesty and a preference for calm and tranquility, they did not want people talking about them. In reality, Mr Frank was mistaken, or else he was deceiving me. An investigation conducted in Amsterdam would, at first, lead me to believe that Schnabel’s book had not been translated into Dutch. Even the Contact publishing house replied or had had others reply to several booksellers and private individuals that the book did not exist. I discovered then that, in a showcase at the museum, the book by Schnabel was said to have been translated and published in 1970 (twelve years after its publication in Germany, France and the United States!) under the title Haar laatste Levensmaanden (Her last months). The book, unfortunately, was impossible to find. Same replies from booksellers and from Contact publishers. By dint of insistence I finally got a reply from Contact saying that there remained only one archive copy. I obtained permission, not without difficulty, to consult it, and then to have photocopies of pages 263 to 304. For, in reality, the book in question contained only an excerpt from Schnabel’s book, reduced to 35 pages, and placed in appendix to the text of the Diary. The comparative study of Spur eines Kindes and of its “translation” into Dutch is of the greatest interest. Of the book by Schnabel, the Dutch can read in their language only the last five chapters (out of thirteen chapters in all). Moreover, three of those five chapters have undergone deletions of all sorts. Some of these deletions are indicated by ellipses. Others are not indicated at all. The chapters thus cut up are IX, X and XIII, i.e. those that concern, on the one hand, the arrest and its direct aftermath (in the Netherlands) and, on the other, the story of the manuscripts. As soon as it is no longer a question of those subjects but rather of the camps (as is the case in chapters XI and XII), the original text by Schnabel is respected. Examined closely, the cuts seem to have been effected to remove any details the least bit telling that were in the testimonies of Koophuis, Miep, Henk and Elli. For example, it is lacking, with nothing to indicate a cut, the crucial passage where Elli tells how she informed her father of the Franks’ arrest (the 13 lines of page 115 of Spur… are completely absent from page 272 of Haar Laatste Levensmaanden). It is an aberration that the only nation for whom a censored version of the life of Anne Frank has thus been reserved is precisely that nation where the adventure of Anne Frank had its inception. Can one imagine revelations about Joan of Arc being made to all sorts of foreign peoples, but forbidden, in a certain way, for the French people? Such a manner of proceeding is comprehensible only when publishers fear lest, in the country of origin, some “revelations” quickly seem suspect. The explanation given by Mr Frank hardly holds. Since Koophuis, Miep, Henk and Elli find themselves named anyhow (and, besides, under complete or partial pseudonyms), and since Schnabel has them say such and such things, one fails to see how the cuts made amidst those remarks might cater to their touchy modesty or assure them more tranquility in their life in Amsterdam. Rather, I would believe that the drafting of the Dutch translation gave rise to very long and laborious negotiating amongst all the interested parties or, at least, between Mr Frank and some of them. The “witnesses”, of course, agreed to collaborate with Mr Frank but, over the years, became more circumspect and stinting with details than in their original “testimonies”.

52) Der Spiegel reveals that there was a reworking and a rewriting – The aforementioned article in Der Spiegel brings us, as I have said, some curious revelations. By principle I distrust journalists. They work too quickly. Here, it is obvious that the journalist conducted a thorough investigation. The issue was too burning and delicate to be dealt with loosely. The finding of this long article could, in effect, be the following: while suspecting the Diary to be a forgery, Lothar Stielau perhaps proved nothing, but all the same he “ran into a really thorny problem – the problem of the genesis of the book’s publishing” (auf ein tatsächlich heikles Problem gestossen – das Problem der Enstehung der Buchausgabe, page 51). And it is revealed that we are very far from the text of the original manuscripts when we read in Dutch, German or in whatever language, the book entitled Diary of Anne Frank. Supposing for a moment that the manuscripts are authentic, one must know, in effect, that what we read under that title, for example in Dutch (i.e. in the supposed original language), is but the result of a whole series of reworking and rewriting jobs, done notably by Mr Frank and some close friends, amongst whom (for the Dutch text) Mr and Mrs Cauvern, and (for the German text) Anneliese Schütz, whose pupil Anne had been.

53) The text’s transformations. The “collaborators” of Mr Frank – Between the original state of the book (i.e. the manuscripts) and its printed state (the Dutch edition by Contact in 1947), the text went through at least five successive states.

- between late May 1945 and October 1945 Mr Frank established a sort of copy (Abschrift) of the manuscripts, in part alone, in part with the aid of his secretary Isa Cauvern (the wife of Albert Cauvern, a friend of Mr Frank’s: before the war the Cauverns had hosted the Frank children at their house for the summer holidays).

- from October 1945 to January 1946 Mr Frank and Isa Cauvern worked together on a new version of the copy, a typewritten version (Neufassung der Abschrift/Maschinengeschriebene Zweitfassung).

- at an unspecified date (end of the winter of 1945-1946), that second version (typewritten) was submitted to Albert Cauvern; as he was a radio man – a “reader” at the “De Vara” station in Hilversum – he was well versed in rewriting. According to his own words, he began by “largely changing” that version; he drew up his own text as a “man of experience” (Albert Cauvern stellt heute nicht in Abrede, dass er jene maschinengeschriebene Zweitfassung mit kundiger Hand redigiert hat: “Am Anfang habe ich ziemlich viel geändert”, page 52). A surprising detail for a diary: he did not shrink from grouping together under a single date letters written on different dates; at a second stage he confined himself to correcting the punctuation and errors of wording and grammar; all those changes and corrections were made on the typewritten text; A. Cauvern never saw the original manuscripts.

- starting from the changes and corrections, Mr Frank established what one may call the third typewritten text in the spring of 1946; he submitted the result to “three prominent experts” (drei prominente Gutachter, page 53), letting them believe that it was the complete reproduction of a manuscript, with the quite understandable exception of a few points of a personal order; then, those three persons having apparently given their endorsement to the text, Mr Frank went on to offer it to several Amsterdam publishing houses, which refused it; turning then, in all likelihood – but this point is not very clear –, to one of those three persons, Mrs Anna Romein-Verschoor, he got her husband, Mr Jan Romein, professor of Dutch history at the University of Amsterdam, to write in the daily Het Parool a resounding article beginning with the words: “There has by chance fallen into my hands a diary [etc.]”; the article being highly laudatory, a modest publishing house in Amsterdam (Contact) asked to publish that diary.

- with the agreement concluded or about to be concluded, Mr Frank went and found several “spiritual counsellors” (mehrere geistliche Ratgeber), amongst whom Pastor Buskes; he granted them full licence to censor the text (raumte ihnen freiwillig Zensoren-Befugnisse ein, pages 53-54). And that censorship was exercised.

54) Der Spiegel is troubled by the Diary‘s German “translation” – But the oddities do not end there. The German text of the Diary is the subject of some interesting remarks on the part of the Der Spiegel journalist. He writes: “One curiosity of the ‘Anne Frank literature’ consists in Anneliese Schütz’s translation work, of which Schnabel said: ‘I wish all translations were so faithful’, but whose text quite often diverges from the Dutch original” (page 54). Indeed, as I shall show further on (sections 72-103), the journalist is quite lenient in his criticism when he says that the German text diverges quite often from what he calls the original (that is to say, doubtless, from the original printed by the Dutch). The printed German text does not deserve to be called a translation of the printed Dutch text: it constitutes, strictly speaking, another book in itself. But let us pass over this point. We shall return to it later.