A dry chronicle of the purge in France in 1944

Summary executions in certain towns and villages of Charente Limousine

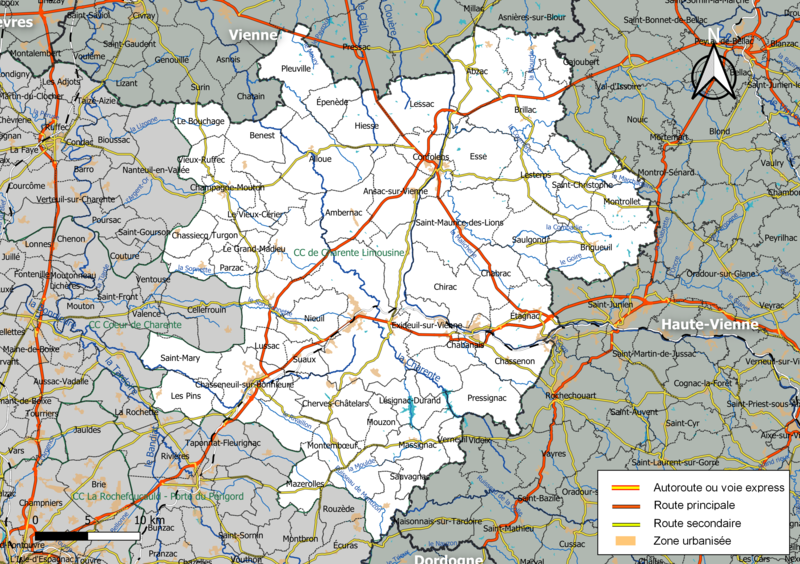

In the course of the 1960s and the beginning of the ’70s, Robert Faurisson began an investigation of the Purge (French: Épuration), limited to those summary executions which took place in the summer of 1944 in a part of Charente known as Charente Limousine, or Confolentais. This meticulous study was to have been published under the title A Dry Chronicle of 78 Days of the Purge in Certain Towns and Villages of Confolentais.

The difficulties Professor Faurisson encountered in his other inquiry, into the gas chambers and the genocide, prevented him from completing his work on the Purge. In no way impairing the possibility of future publication of the full Chronicle, the French Revisionist journal Revue d’histoire révisionniste (no. 4) published in spring 1991 several excerpts from the uncompleted work. The Journal of Historical Review, accordingly, thanks Professor Faurisson and the Revue for enabling us to bring portions of this important (and much neglected) chapter of the history of the Second World War to American readers.

Professor Faurisson has catalogued the executions attributable to two maquis, or guerrilla bands, that held sway over the southern part of Confolentais and made occasional incursions into the extreme west of the department of Haute-Vienne. The “Maquis Bernard” and the “Maquis Chabanne” are the two maquis in question. The first, a Communist maquis, was a force in the environs of Chabanais-sur-Charente; the second was socialist, or centrist, and active around Chasseneuil-sur-Bonnieure. Chabanais and Chasseneuil are on RN 141, which runs from Angoulême to Limoges.

The four extracts that we publish here are:

– Some executions by the “Maquis Bernard”;

– “Shot by firing squad in her wedding gown,” the story of Mlle. Armagnac, a victim of the “Maquis Bernard”;

– Some executions by the “Maquis Chabanne”;

– “Death of a Priest under Torture”, the story of Father Albert Heymès, a victim of the “Maquis Chabanne.”

The first extract was published, though with grave typographical errors, in Maurice Bardèche’s monthly review Défense de l’Occident (July-August 1977, pp. 44-49).

The second extract, concerning Mlle Armagnac, was communicated, along with much other information, to Henri Amouroux in January of 1988. The latter thereupon made substantial use of it in volume 8 of La Grande Histoire des Français sous l’Occupation, under the title “Joys and Sorrows of the Liberated People (6 June to 1 September 1944)” (published 10 October 1988 by Robert Laffont). In the list of 575 persons to whom Henri Amouroux tenders his thanks, the name of Robert Faurisson is not included.

The third extract has never been published, but was sent to Henri Amouroux, who used it to some advantage.

The fourth extract appeared in Les Écrits de Paris (March 1986, pp. 40-48) under the title “The Purge: From the death of a priest to truncated statistics [of the Purge].”

– I –

Some Executions by the “Maquis Bernard”

(15 June to 11 August 1944)

Responsibility for the executions by the Communist “Maquis Bernard” rests with Bernard Lelay, a printer at L’Humanité, the daily newspaper of the French Communist Party, and with his followers. After Bernard Lelay, the person most directly implicated in the executions was Augustin Raoux, known as “Gandhi.” A Jewish convert to Catholicism, Raoux was a solicitor at Ruffec. Assisted by his son Philippe, he directed the Deuxième Bureau (Security and Intelligence). He was both prosecutor and judge. The accused had no attorney, and there was no question of last rites for those condemned to death. The corpses were not put into coffins. The dead were not restored to their families. Very expeditious, this maquis seldom used torture. Junien B., native of La Péruse, killed François Destempes by means of torture. Militiaman[1] Labuze was tortured at the rectory of Saint-Quentin and then shot.

Bernard Lelay died in 1975. In 1977, his ashes were removed to the crypt of the Memorial of the Resistance at Chasseneuil-sur-Bonnieure.

Among the 72 or 73 cases enumerated below, there are 14 women. Among them one who was executed in her wedding gown (see below); and another, 22 years of age and mother of two, who was shot when 7 months pregnant. The oldest of those shot was a 77-year-old farmer; the youngest, a schoolboy 16 years of age.

The names followed by an asterisk are those of persons on behalf of whom their families, after the war, obtained the mention “Died for France.”

(Before 15 June 1944, this maquis carried out executions in the forest of Rochebrune, near Étagnac. On 1 June: three German prisoners, an unnamed girl, and gendarmerie warrant officer Pierre-Léon Combas (*); on 12 June: chauffeur Sylvain and watchmaker Vignéras. On the same day, two German railway workers were killed at Roumazières; their bodies are still there on the estate of the château of Rochebrune, near Étagnac.

After 11 August 1944, the same maquis carried out many executions in regions other than the one of interest to us here, which is roughly that of the Pressac château, situated near Chabanais [Charente].)

- 15 June, Mme. Chevalier, St-Maurice-des-Lions, housewife, aged 53.

- 17 June, Mme. Beaumatin, Exideuil, schoolteacher, aged 33.

- 17 June, Général Nadal, Chantrezac, brigadier general, aged 65.

- 17 June, Marcel Nadal, Chantrezac, student, aged 22 (son of the preceding).

- 20 June, Charles Besson, Chabanais, school principal, aged 46 (one or more of his former pupils were in the firing squad).

- 20 June, Antoine de Cazes, Verneuil, landowner, aged 43.

- 20 June, Charles Schwieck, Verneuil, aged 21.

- 20 June, 1 unnamed German soldier, Verneuil.

- 26 June, Marie-Charles Soury-Lavergne, Rochechouart, importer, aged 74 (his wife would be executed on 24 July for having protested).

- 26 June, Pierre V., St-Junien, worker, aged 33 (member of the maquis accused of theft).

- 27 June, Pierre, also known as Julien, Sardin, La Péruse, carpenter (killed).

- 27 June, Mme. Steiner, Roumazières, housewife, aged 41.

- 27 June, Michel Steiner, Roumazières, pedlar, aged 45.

- 27 June, Jean Steiner, Roumazières, laborer, aged 20.

- 27 June, Albert Steiner, Roumazières, laborer, aged 19.

- The last four persons mentioned and Jean Bauer, executed on 30 June, were members of one and the same family from Moselle.

- 28 June, Auroyer (no other information).

- 28 June, Alfred Desplanques, Suris, tenant farmer, aged 43 (father of eight children).

- 30 June, Mme. Gingeot, St-Junien, bookseller, aged 35 (found with both feet cut off after being strung up with wire by the ankles).

- 30 June, Marie-Louise Texeraud, St-Junien, office worker, aged 48.

- 30 June, Henri Charles, Roumazières, factory director, aged 45.

- 30 June, Serge Bienvenu, Roumazières, accountant, aged 39.

- 30 June, Jean Bauer, Roumazières, pedlar (brother of Mme. Steiner), aged 36.

- 4 July, Régis Trillaud, Roumazières, watchmaker, aged 34.

- 4 July, Gaston Louis, Nice, detached guard of the Militia (transported blankets).

- 4 July, Raymond Auxire, Confolens, aged 19.

- 4 July, Germain Demontoux, St-Maurice-des-Lions, clerk, aged 24.

- 4 July, Georges Maillet, St-Junien, workingman, aged 42.

- 4 July, Germaine Maillet, St-Junien, housewife, aged 33 (wife of Georges Maillet).

- 5 July, Maurice Verger, Vayres, farmer, aged 36.

- 5 July, Françoise Armagnac, bride of Pénicaut, Exideuil, aged 26 (grandniece of Sadi Carnot, French president assassinated in 1894; arrested on 4 July by Nathan Lindner after the wedding mass; shot in her wedding dress).

- 6 July, 1 unidentified male (body rolled up in a blanket at the foot of the prisoners’ tower of the Pressac chateau).

- 6 July, 1 unidentified male (head stoven in; same place; confusion with the above?).

- 7 July, Siméon Israel, Manot, railway worker, aged 42.

- 9 July, Mme Lévêque, St-Laurent-de-Céris, housewife, aged 65 (“the nurse”).

- 10 July, Auguste Sibert, Loubert, livestock dealer, aged 29.

- 11 July, Henri Malga, Rochechouart, workingman, aged 43.

- 12 July, Raoul Chevalier (*), Maisonnais, justice of the peace, aged 60.

- 12 July, Maurice Aubert, Montemboeuf, notary, aged 31.

- 12 July, Jacques de Maillard, Chassenon, landowner, aged 50.

- 13 July, Jean Jonquet, Étagnac, restaurateur, aged 63.

- 13 July, François Destempes, Chabanais, town clerk, aged 49 (death by torture).

- 13 July, Léonard, alias Adrien, Saumon (*), Maisonnais, clog maker (former mayor with socialist leanings).

- 16 July, 1 unidentified male (body rolled in a blanket, in back of the château farmhouse).

- 16 July, Pierre Carlin (*), Brigueil, seed oil producer, aged 25 (was a member of the Resistance network “Action R3”).

- 16 July, Mme. Noël, St-Junien, nurse, aged 35.

- 16 July, Eugène Écoupeau, Magnac-sur-Touvre, fitter, aged 21.

- 18 July, Mme. Baatsch, Exideuil, housewife, aged 45.

- 18 July, Henri Fabre, Roumazières, radio electrician, aged 42.

- 18 July, 1 unidentified girl, came from Rouen.

- 18 July, Pierre Sauviat, Chabanais, retired gendarmerie warrant officer, aged 61.

- 18 July, Sylvain Vignaud, Confolens, grain inspector, aged 58.

- 20 July, Gaston Devoyon, Chabanais, carpenter, aged 50.

- 20 July, Amédée Devoyon, Chabanais, carpenter, aged 45 (brother of Gaston Devoyon).

- 21 July, Ferdinand Gisson, Chabanais, seed merchant, aged 60 (deputy mayor; killed).

- 24 July, Jean Codet-Boisse, Oradour-sur-Vayres, lumber worker, aged 28.

- 24 July, Pierre Sadry, Rochechouart, pastry cook, aged 60.

- 24 July, Mme. Soury-Lavergne, Rochechouart, housewife, aged 57 (husband executed on 26 June).

- 27 July, Angel Besson, Roussines, bus driver, aged 24.

- 27 July, Mme. Besson, Roussines, housewife, aged 22 (spouse of Angel Besson; mother of two young children; 7 months pregnant).

- 29 July, Eugéne Pannier, Manot, landowner, aged 54.

- 30 July, Jacques Labuze, St-Junien, medical studies completed, aged 30.

- 30 July, Mme. Lagarde, Étagnac, housewife, aged 24 (“la belle Manou”).

- 31 July, Yvon B., Limoges (?), aged 17 (had reported a maquis?).

- 4 August, Paul Corbiat, Montemboeuf, farmer-landholder, aged 77.

- 4 August, Jacques Londeix, native of Bordeaux, schoolboy, aged 16.

- 6 August, Gustave Nicolas, Chasseneuil, tradesman, aged 47.

- 11 August, 1 unidentified male (found 150 meters east of the cemetery of Vayres).

- 11 August, René Barbier (*), Alloue, working landowner, aged 37.

- 11 August, Aloyse Fritz, Rochechouart, gendarmerie warrant officer, aged 43.

- 11 August, Pierre Marot, Rochechouart, gendarmerie warrant officer, aged 34.

- 11 August, Jeanne Lamothe, Chantilly (Oise), stenographer typist, aged 19.

- 11 August, Jean Paillard, Rochechouart, commercial traveler, aged 45.

- 11 August, Georges Remondet, Confolens, lieutenant retired on pension, aged 54.

– II –

Shot by firing squad in her wedding gown

DOCUMENT: Death Certificate

Office of Mayor of Saint-Quentin (Charente):

Madame PÉNICAUT, née Françoise Charlotte Solange ARMAGNAC, on 23.02.18 at Paris, residing at Bel Air, village of Exideuil/s/Vienne (Charente), farmer, aged 26.

Died at Pressac, village of Exideuil/s/Vienne, on 5 July 44 at 9 p.m.

Françoise Armagnac was the daughter of Jean-Marie Armagnac, a Senate official, and of Ernestine Marie Carnot, niece of Sadi Carnot. Through her mother, she was thus the grandniece of the president of the Republic, who, in 1894, had been assassinated at Lyon by the anarchist Caserio.

Along the Angouême-Limoges main road, in the vicinity of Chabanais but within the limits of the village of Exideuil, Françoise Armagnac lived with her mother in a Basque style chalet in the locality of Bel Air. Her uncle, Jean Carnot, resided in a house of imposing size in the locality of Savignac.[2] This house, where Françoise and her sister Cècile, coming from Paris, used to spend their vacations, is improperly designated with the term “château” by certain inhabitants of the region, as well as by the ordnance map. Françoise Armagnac, contrary to the legend, was not the inhabitant of a château.

The narrative you are about to read owes its content essentially to the oral testimony of her husband and a written account left by her mother. The narrative is followed by sworn statements.

The account

The religious wedding ceremony of Françoise Armagnac and Georges Pénicaut was held at eleven o’clock in the morning on Tuesday, 4 July 1944, at the church of St-Pierre-ès-Liens de Chabanais. The sparse (?) audience included the Girl Scouts and Jeannettes with whom Françoise busied herself, and whose leader she was. A sermon was delivered by Mr. Jagueneau, the Catholic priest and dean of Chabanais; less than a month previously, the latter had had dealings with the maquis in connection with the burial of “the Spaniard”;[3] on the afternoon of that same 4 July, he would be slapped in the face by a member of the maquis.

The ceremony went off without incident. To be sure, it seems that disturbing rumors had circulated the night before, but the couple had known nothing of these. Françoise wore a white silk dress, long and full, as well as a diadem of white roses, a white mantilla and her sister Cècile’s white burnoose. It was in this wedding outfit, give or take a few items, that she was to be shot to death some thirty hours after the wedding.

The wedding breakfast was planned for the chalet of Bel Air. Instead of taking the main road, the couple and some of the guests took a shortcut across the fields. About 300 meters before reaching the chalet, a very considerable group of maquisards (members of the maquis) appeared and began a peremptory questioning of the entire wedding party. To believe the adjudant [noncommissioned officer = warrant officer junior grade], all this was a prelude to a simple search; he even added that it would be no more than “a call on the family of a former president of the Republic.”

A dozen of the wedding guests were placed under close watch in an outbuilding of the chalet. The Catholic dean was put in a separate room, and it was there that he would be slapped. The photographer, Mr. Aubineau, was isolated in another room; he was suspected of having photographed the maquisards on the day they occupied Chabanais.[4]

Maquisards seated themselves at the table set up in the main room of the chalet and divided up the wedding breakfast. In the middle of the table there were blue hydrangeas that had been gathered from outside the house, and two bouquets of white roses. The maquis distributed cakes and chocolates to the Scouts and Jeannettes.

Around three o’clock in the afternoon the other participants in the wedding would be allowed the cold remains of the meal. At about five o’clock, the guests invited to the wedding feast arrived and in turn were searched. At six o’clock the bride and groom were taken and put into a truck along with the photographer and the Catholic dean. As Françoise had to stand in the truck, one of the maquis had gone to find a chair for her from the drawing room. And thus began what, leaning towards her husband, she called “our honeymoon trip.” It is unlikely that the couple at that moment really felt themselves in danger. No one attempted anything in their behalf, no doubt precisely because no one feared any fatal consequence. No one save the very young housemaid, Louise V., who declared to Anna, the cook, that Françoise was going to be shot.[5] She said she was a nervous wreck, and that very evening, taking her belongings, she quit the premises. She would not be seen again. She had guided the maquis during their search, and it was she who had led them to an etagere where there was a little wooden clog: in this little clog an insignia of the Militia was discovered. That at least seems evident from what Mme. Armagnac, Françoise’s mother, would hear at the Vayres camp where, a few days later, she in her turn would be interned by the maquisards.[6]

The chalet was stripped of all objects of value. Yet the adjutant had declared that “not one sou, not one centime would be taken”; that “the maquis had no need of anything.” “Besides,” he had specifically stated, “look at how we’re dressed!” But itis probable that on discovering, at the time of the search, seemingly damning evidence against Françoise, the order had been given to “salvage” everything. With the arrival of 126 men (on foot) and two trucks, the maquisards, taking one of the trucks, carried off the silverware, the clocks and watches, the family jewels, money, the brandy and the wine, plates and dishes and all the food. In particular, they took Mr. Armagnac’s watch (he had died in 1942) and the contents of the purses of the two children, ages six and eight, who had come to spend their vacation at Bel Air. They left the purses.[7] As for the truck carrying away the prisoners, it traversed Grenord and reached the Pressac château, near Saint-Quentin-sur-Charente. The guards were singing. One of them broke into the “Internationale,” but his comrades interrupted him, reminding him that “it is forbidden.” The arrival at the château was tumultuous. The maquisards were abusive, ready to beat the prisoners black and blue, but “Bernard” came out of the château, a club (?) in his hand, and warned: “I’ll clobber the first one who touches them.”

The prisoners were placed together in a room on the left of the second story that would serve as their prison. Meanwhile, Françoise was conducted to the infirmary on the right. Her identification papers, her bracelet, her watch, and her engagement ring were taken from her. The famed “nurse” the former maidservant of Mme. Vissol, living in Chabanais — would be seen, after these events, wearing that engagement ring on her finger.

Françoise and her husband underwent two joint interrogations in the office of Raoux, called “Gandhi,” who functioned at one and the same time as examining magistrate, public prosecutor and judge. A diary belonging to Françoise was examined closely: that for 1943, in which she told of having attended the first meetings of the Militia (four meetings in all, it seems). “This is sufficient,” Raoux is supposed to have said, showing her the insignia of the Militia.

There were about fifteen men locked up in the prison of the Pressac château. The new arrivals were given nothing to eat; no doubt they had arrived too late. The following day, Wednesday, 5 July, still nothing to eat. Georges Pénicaut was put to work on the charcoal detail. Françoise Pénicaut sewed forage caps in the infirmary. She asked for and obtained a piece of bread. In between their forced labor, the couple succeeded in exchanging a few words. That morning Françoise was summoned twice for questioning. She would confide to her husband that they were forever asking her the same questions and that she was sure she would be condemned. At morning’s end, she was told that her execution was for that same evening, whereas Georges would have to be released. Georges obtained an audience with “Bernard.” He implored him to take his life in exchange for that of his young wife. Far from yielding, “Bernard” enumerated for him the exhibits which proved Françoise’s guilt: her Militia insignia, her diary for 1943, her signed deposition. He even read him an excerpt from the diary in which her joining the Militia was related. Thereupon Georges mentioned the page of the diary where Françoise made reference to the certified letter by which she had sent the Militia her resignation. At once “Bernard” resumed reading the diary; coming to the date of 7 August 1943, he tore out the page and declared to Georges Pénicaut: “The evidence that interests us, we keep; the things that don’t interest us, we have the duty not to look at[8].” And he added that the execution would not be delayed “by one hour or by one minute.”

At 9 o’clock in the evening, Françoise was executed right at the top of the meadow called “The York,” behind a thicket and close to a drained fishpond.[9] Before leaving for the place of the execution, she was granted five minutes to wait for her husband, who was not yet back from his fatigue duty. Upon his return, she rushed to him, and they were able to exchange a few words. To the firing squad she is supposed to have declared: “Kill me. I entrust my soul to God.” We have several witnesses to her sangfroid. The coup de grâce was supposedly fired by “the nurse.” They refused to show Georges the place where his wife’s body had been thrown, and he asked for the return of the engagement ring in vain.

Exhumation could not be effected until five months later, in the mud, on 2 December 1944. Today, Françoise Pénicaut has her grave in the cemetery of Chabanais. The inscription on the gravestone reads: “Here lies Françoise Armagnac, wife of Pénicaut, 1918-1944.” To her left, the grave of her father bears the words: “Jean Armagnac, born in Paris, deceased at Bel Air, 1872-1942.” On her right is the grave of her mother, where one may read: “Marie Armagnac, née Carnot, 1877-1969.”

The Testimonies

• Testimony of Cécile Armagnac, elder sister of the slain woman:

At the time of the events in question, I was an ambulance nurse in Cherbourg. Because of the battle of Normandy, the town was cut off from the rest of France. I only learned of the marriage and the death of my sister around the end of the month of August 1944, and then only by chance (someone who came from Paris and was passing through Cherbourg had, on hearing my name, offered me his condolences …). We didn’t do anything political, my sister and I. We were both against the occupying forces. The Militia seemed at the time it was created, in 1943, like a sort of civil gendarmerie charged with maintaining order in the country. In an area like ours, where there were, so to speak, no Germans in 1943, the Militia was not considered pro-German, as it later came to be, especially as viewed from Paris or the areas where the members of the Militia and the Germans took part in the same operations of “maintaining order.” Besides, Françoise was going to go in for the social work of the Militia, that is to say first aid, packages for the prisoners of war, day nurseries for children. She went, I believe, to only four meetings of the Militia, after which she sent in her resignation as early as 7 August 1943.

I returned to Bel Air on 9 October 1944, that is to say three months after the death of my sister. The area had already been liberated for two months. People were turning their backs on my mother. The tenants were no longer paying her rent. I learned, moreover, that after the Chabanais disaster of 1 August 1944, people had come to Bel Air and commandeered wood and furniture (beds, dressers, wardrobes) for the victims. Among others, B., who was very well known for his Communist opinions, had come looking for furniture. Subsequently we were to be given back only an ebony wardrobe and a mahogany dresser. I also learned that my mother had been taken away and imprisoned by the maquis. She was 67 years old and nearly blind. In a letter addressed to the assessor, she had solicited a reduction in taxes in view of the looting of Bel Air, in which all of her available cash had been taken from her. Her letter had been intercepted. She herself had been arrested, just as the Chabanais tax collector had been. Raoux and other interrogators had tried in vain to make her retract the terms of the letter. Sure of being shot, she resisted them. They also tried to extort a sum of money from her, as they had from a certain G., of Saint-Junien. She told them they had already taken everything from her. Ultimately the maquisards released her from the Vayres camp just as they were precipitously departing it. My mother, cutting herself a staff from the hedgerow, marched a good 20 kilometres to get back to Bel Air.

Those events were the product of a troubled era. It wasn’t any prettier on the other side. In times like those, actions are often faster than thoughts, with excesses of all kinds as a result. And things leave their mark.

• Testimony of Robert du Maroussem, former commanding officer of the local Militia:

I remember that at the end of one of our information briefings, Mlle. Armagnac told us: “You go too far in your attacks on the Jews and the Freemasons; they’re being hunted down these days.”

• Testimony of Mme T., former domestic of the Pressac château:

When the truck arrived at the château, the maquis, in order to mock her, cried: “Long live the bride!” She slept in a loft. They made her clean the toilets and sew clothing. Her dress was soiled. When she crossed the yard, they continued to cry: “Long live the bride!” A young fellow who was a member of the firing squad was impressed by her courage. It seems that she opened the front of her burnoose and told them: “Fire away!”

• Testimony of Nathan Lindner, instigator of the arrest:

[In her written statement, Mme. Armagnac names the “newspaper vendor Lannaire (sic), born in Warsaw and a refugee in Chabanais.” She adds that this man directed the looting of Bel Air and that he personally carried off “the genealogical tables of the Carnot family.” He supposedly boasted of the “fine stroke” he had pulled off and exclaimed: “Won’t they think I’m something after that!” — I managed to find Nathan Lindner on 14 May 1974. He was then living in the Halles quarter of Paris and had a newspaper stand at the corner of Tiquetonne and Montorgueil streets. Born in Warsaw in July of 1902, he had been a corporal in the Foreign Legion (height: 5 ft 2½ in). During the war of 1939-1940, he had worked in Toulouse for Paris Soir; later, because of the Vichy racial laws, he had worked in Issoudun (Indre) for himself. He finally went back to Chabanais, where he peddled newspapers for the Hachette Store run by Mme. Olivaux. Known by the nickname “Trottinette,” in the Resistance he used the pseudonym “Linard.”]

I had to leave the Chabanais area in 1945 on account of those stories of the Liberation. The newspapers of the time, and especially L’Essor du Centre-Ouest, had violently attacked me. A good many years later it was Historia that lit into me.

In 1944, at Chabanais, I took delivery of the newspapers at the railroad station and brought them to the Olivaux store. I had a pushcart fitted out with bookshelves. That’s why they nicknamed me “Trottinette” [scooter]. One day I hear her say something like: “These young people who refuse the S.T.O. [Service du Travail Obligatoire = Compulsory Work Service] should be doused with gasoline and set on fire.” Other people could confirm that for you.[10] One of my newspapers was Signal, the only magazine comparable to today’s Match.[11]

I was the one who talked to Bernard about Françoise Armagnac. I asked to take care of the search and the rest of it. Bernard gave me carte blanche. When the wedding party got to within 300 meters of the Armagnac property, I told them that we were members of the maquis and not looters, and I read an order that said any man caught looting would be shot immediately. We set up the operation on the same day as the wedding in the hope that we’d find other members of the Militia among the guests. In the course of the search we discovered appointment books, armbands, insignia[12], a Militia membership card.[13] I took the bride to Raoux, who, provided with my written report, conducted the questioning and decided on the execution.

What I did that day was perhaps not very pretty. I entered into history through the death of a descendant of Sadi Carnot. I’m not pleased about it. It had to be done at the time. I’m not a bloodthirsty person; feelings were running very high and people weren’t in any state to be reasoned with.

But right now we have lots of people who are doing a lot of harm [now, in 1974]. They ought to have been executed at the time instead of being liberated and whitewashed. All these people besmirch and denigrate the Résistance.

The witness appeared to me to be tormented by the “Armagnac Affair.” He does not regret having had the bride shot, but he deplores the vexations that ensued for him. He says he was always a Communist and affirms that he was expelled from the Party in 1945 for having wanted, contrary to instructions, to help the Spanish Reds arm themselves in order to liberate Spain from the yoke of Franco. Among those Reds, there was “Ramon.” Nathan Lindner is mad for history and painting; he paints under a pseudonym (Ainel, as in N[athan] L[indner])].

• Testimony of Annie F., former “Wolf Pup” scoutmistress:

Françoise Armagnac was an idealist and an enthusiast, an ungainly girl, eccentric and sometimes careless in dress. Very much the churchgoer, she was brusque in manner; she was very peremptory, and perhaps timid at bottom. Politics didn’t interest her. Once, speaking to me about a movement, perhaps of the Militia’s social work or women’s movement, she told me that in an age like ours, you couldn’t remain indifferent, that this movement looked interesting and that one ought to be able to make oneself useful in it. Someone was it her mother or was it perhaps myself cautioned her and counseled her to get the advice of the Scouts at the national level.[14]

On 4 July 1944, I witnessed the removal of the Armagnac family belongings in the maquisards‘ truck. Children were playing on the slope of the meadow; it was the “Wolf Cubs” and the Girl Scouts.

• Testimony of Joseph L., former president of the Legion:

At one moment, at Bel Air, young Valette, who was one of the maquisards, cried out: “The Germans are coming! There are the swastikas!” It was Scout crosses.[15]

• Testimony of the widow of Lieutenant Robert,chief of operations:

[Lieutenant Robert’s true name was Jean P. He was a farmer at Les Fayards, a village near Étagnac. His widow now (1974) has an antique shop in the Paris suburb of Saint-Mandé.]

My husband has just died of cancer at the age of 52. I met him after the Liberation. He was a croupier then. For two seasons he managed the casino of L. I wasn’t familiar with the Resistance in Charente. I don’t come from there. My husband was always a Communist. He never talked, so to speak, about his memories of the maquis. He was sickened by the ill that was spoken of the Resistance. Basically, he really began to talk about the maquis only during the eight months in the hospital preceding his death. He talked especially about “Gustave” (Bricout), and then he also spoke about a marquise or a countess that had been shot. He was there. I don’t remember well at all. Hadn’t that woman denounced some Frenchmen? My husband thought that it was just … I think that my husband didn’t agree all that much …”[16]

• Testimony of G.B., of Montbron, alleged witness to the execution:

Then the bride opened her veil and she called out just like that: “Long live Germany!”[17]

• Testimony of “Bernard,” commander of the “Maquis Pressac” [or “Maquis Bernard”]:

The bride? She was secretary of the Confolens Militia.[18] She told me: “You’ve got the better of me, but if I had got the better of you, it would be no different.”

• Testimony of “Gaston,” chauffeur for “Bernard”:

I took part in the arrest of the Carnot girl. A sensational girl. Facing the firing squad, she took hold of her wedding dress like this [gesture with both hands of baring the throat]. She never lowered her eyes. She was a chef de centaine in the Militia.[19]

The “Armagnac Affair” as told by Robert Aron:

[Histoire de l’Épuration, volume I, “Les Grandes Études Contemporaines,” Fayard, 664 pp., 1967, pp. 566-567.]

“Perhaps the most detestable acts of violence are those which attack women. Near Limoges, a young woman of the region, Mlle. d’Armagnac, whose family are proprietors of a château, gets married in the church of her village: when she comes out on the parvis from the mass, maquisards kidnap her, her husband, the priest who married them and a witness. At dawn the next day she is shot dead in her wedding gown. Motives given: first, she is the daughter of the manor house; second, she has given care to militiamen[20].”

Testimony of P. Clerfeuille, Professor at Angoulême

“You know, it is very difficult to do this work on the Repression. People don’t want to talk. Let us take an example. I am positive that a woman was shot dead in her wedding gown. I went to Chabanais to investigate. I have an official card for doing this kind of work: I’m a corresponding member of the Committee on the History of the Second World War. We are under the jurisdiction of the Prime Minister. Well, they refused to give me the name of the woman who was shot! I went away without a thing. And nevertheless I know that woman existed.”

[P. Clerfeuille is officially charged, among other tasks, with research on the Repression at the Liberation (i.e., on the Purge) in the department of Charente. Our interview took place in 1974, say seven years after the publication of Robert Aron’s book.]

Two Documents

• 1 / First Battalion, 2406th Company. 4 July 1944

Report of the Company Lieutenant[21]

Today we carried out a large-scale operation at the Armagnac château; place known as Petit Chevrier[22] concerning the possible arrest of militiamen. The operation was completely crowned with success because we arrested a militiawoman. This woman was getting married today and we came at the height of the wedding or at least at the arrival of the wedding party. We interrogated the guests one after the other, and I personally verified their identity and all the papers that were in their possession as well as their wallets. After verification, I detained a photographer named Aubinot[23] who allegedly photographed the maquis the day we occupied Chabanais. This requires a serious investigation at his domicile.

I also detained the Priest of Chabanais who had prevented the bringing of flowers and wreaths and the flag into his church.[24]

Afterwards we kept a close watch on the Bridegroom and the Bride for having answered us spitefully concerning the work we were doing at their home. Then we made a regulation search without damaging anything up to the moment when we found the evidence that the Bride is a Militiawoman. And so from that instant I all but gave the men a free hand for the removal of the provisions and other things worth our while.

When everything was loaded, we had the prisoners get into the trucks and we returned without incident.

I am satisfied with that expedition because I saw my men at work and I see that I can count on them.

As for my Adjutant-Chef [senior warrant officer] Linard[25], I can only thank him for having mounted this expedition and to have supervised it so well. Also, with the consent of the commanding captain of the battalion, I shall request that he be named company adjutant.

In the evening a German airplane flew over the camp at a low altitude and on its way to Pressignac loosed a few bursts of machine-gun fire on civilians.

Signed: Robert

• 2 / First Battalion – Intelligence Service — Activity of the Intelligence Service – 7th of July 1944.

Closure of the inquiry on the money and property claimed by the Armagnac family.

[…]

8 July 1944,

The Chief of the Intelligence Service

Signed: Gaudy[26]

III. Some Executions by the “Maquis Chabanne”

(4 July to 17 August 1944)

This maquis was started by three teachers from the secondary school of Chasseneuil: André Chabanne, Guy Pascaud and Lucette Nebout. These three were later joined by a career military man: Jean-Pierre Rogez. André Chabanne died in an accident in 1963. His body rests in the crypt of the Memorial of the Chasseneuil Resistance beside the body of Bernard Lelay, head of the “Maquis Bernard.” Guy Pascaud was arrested on 22 March 1944 and deported; upon his return from deportation, he embarked on a political career; he died some years ago. Lucette Nebout changed her name following a remarriage; she is still living. After the war, Jean-Pierre Rogez had a brilliant military career; he was chief of staff of a general in command of the Paris garrison. On his retirement, he embarked on a political career and became for a time the mayor of Malaucène (Vaucluse). In the summary of his service record are these four words: “tortured by the Gestapo.” The truth is that he was accidentally knocked off his motorbike by a German military vehicle.

The “Maquis Chabanne” – also called “Bir Hacheim, AS 18” – killed less but tortured more than the neighbouring Communist “Maquis Bernard.” The responsibility for its executions or tortures is also more diverse, divided between André Chabanne and a few members of his entourage, in particular François-Abraham Bernheim (of Colmar) and the former Saint-Cyr cadet, Jean-Pierre Rogez. Bernheim, of Jewish extraction – as was Raoux, his counterpart for the “Maquis Bernard” – directed the Deuxième Bureau (Security and Intelligence) until one day when André Chabanne dismissed him, probably because he found him too severe.

Whereas in the case of the victims of the Communist maquis almost all the bodies have been exhumed, the victims of the maquis “AS” (“Secret Army”) have not all been exhumed, and it is with full knowledge of the case that the authorities persist in refusing these exhumations. In the village of Montemboeuf, at the locality known as “the fox holes,” near the old Jayat mill, there are bodies which have never been claimed, and others which have been claimed but which the authorities do not want exhumed.

The most astonishing of the executions carried out by the “Maquis Chabanne” are those of the “Couture Seven” as well as that of Father Albert Heymès and his female servant (see below).

Couture (280 inhabitants in 1944) is a village situated north of Angoulême, at the beginning of Charente poitevine, in the proximity of Mansles and Aunac. In June of 1944, a skirmish between German and Militia troops on one side and a small detachment of the “Maquis Chabanne” (five persons in all) on the other resulted in one dead on the side of the maquis.

The couple in charge of this little detachment were convinced that the inhabitants of Couture had denounced them, and Chabanne had ended up having seven persons of the village arrested: a father and son, another father and son, two brothers, and a seventh man. All were tortured, as a Military Justice report would establish after the war. All were shot at Cherves-Chatelars, near Montemboeuf, on 4 July 1944. The bodies were thrown into a cesspool. It would take their families 28 years of petitioning to obtain the exhumation of the bodies and their transfer in secret to the Couture cemetery. Proof of the denunciation was never produced. The presence of this small maquis was a matter of public knowledge in the region.

In the period from 4 July to 17 August 1944, and limiting myself strictly to the region where it was then to be found, this maquis carried out around 50 executions.

Of the 50 cases, seven were women (one of them was 77 years old; she was shot along with her sister, 70 years of age, and the latter’s husband, aged 73, a cripple on crutches). There were also four members of a single gypsy family (one of them a woman) among the victims, and three German soldiers, including one who had tried to escape.

- 4 July, Louis-André Michaud, aged 34, warrant officer pilot on armistice leave, killed at Labon, village near Chasseneuil.

- 4 July, seven farmers from Couture executed at Cherves, all after torture:

Léon Barret, aged 38, brother of the following.

Eugène Barret, aged 32, brother of the preceding.

Èmilien Gachet, aged 61, father of the following.

Èmile Gachet, aged 23, son of the preceding.

Frédéric Dumouss(e)aud, aged 63, fatherof the following.

Marcel Dumouss(e)aud, aged 35, son of the preceding.

Albéric Maindron, aged 32. - 5 July,? Aurance, executed at Cherves.

- 5 July, unidentified male, executed at Cherves.

- 6 July, Joseph Grangeaud, aged 68, tradesman, executed at Cherves.

- 6 July, Édouard Lombreuil, aged 61, insurance broker, executed at Cherves.

- 6 July, André Abadie, aged 33, former stevedore at Bordeaux (?), executed at Cherves.

- 10 July, Jean Veyret-Logerias, aged 67, town clerk, executed at Cherves.

- 11 July, Father Albert Heymès, died by torture, or following torture, at the Priory of Chatelars.

- 13 or 14 July, Nicolas Becker, aged 57, pharmacy assistant, executed at Chez-Fourt, village of La Tâche.

- 16 July, Ernest Schuster, aged 24, interpreter at the Kommandantur [garrison headquarters] of La Rochefoucauld, tortured and executed at Cherves.

- 26 July, Jean Dalançon, aged 49, watchmaker, executed at Cherves.

- 26 July, Jean Niedzella, aged 24 (?), killed at Cherves.

- 29 July, then 30 July for the last of them, four itinerants of the same family (gypsy), killed near Saint-Claud:

Jules Ritz, aged 50.

Pauline Jauzert, aged 57.

Émile Ritz, aged 22.

François Ritz, aged 24. - end of July, three German soldiers were taken prisoner. The sergeant tried to escape; he was killed. His two comrades were fetched, and also killed. The marks of the bullets are still there on the exterior wall of the covered playground of the school at Cherves. The three bodies were thrown into a pond “chez Veyret”; they remained in the pond for at least ten years – with their feet sticking out.

- 1 August, Joséphine Adam, aged 29, servant of Father Heymès, executed at Cherves.

- August, Marie-Germain Groulade, aged 48, housewife, executed at Cherves.

- The following executions took place at the “fox holes” near the old mill at Jayat, in the village of Montemboeuf, where Jean-Pierre Rogez had his command post and where he had a “concentration camp” (its official designation) set up:

- 7 August, Maurice Launay, aged 25, farm domestic; his wife (Mme. Horenstein, of Objat) did not succeed in obtaining exhumation.

- 9 or 10 August, Mlle. Clémence Choyer, aged 65, retired school-teacher, no family; not exhumed.

- 10 August, Augustine Alexandrine Bossu, aged 77, almost blind, sister-in-law of the following.

- 10 August, Victor Maisonneuve, aged 73, invalid needing two canes, husband of the following.

- 10 August, Juliette Henriette Maisonneuve, aged 70, wife of the preceding.

- 11 August, Marie Brénichot, aged 46, tradeswoman.

- 14 or 15 August, Joseph Schneider, aged 25, interpreter at the Kommandantur of Champagne-Mouton, tortured; not exhumed.

- 14 or 15 August, Paulette Marguerite François, aged 27, café owner; not exhumed.

- 15 August, 6 or 7 or 9 Russian volunteers in the German army were executed; no exhumations despite negotiations.

- 16 August, Raphaël Gacon, aged 18 (?), “half day-laborer, half sacristan”; not exhumed.

- 17 August, Emmanuel Giraud, aged 24, farm domestic; not exhumed, despite the apparent request of a brother.

- It might be well to add to this list the name of Octave Bourdy, aged 53, a grocer, executed belatedly, on 6 December in terrifying circumstances at Saint-Claud.

– IV –

Death of a Priest Under Torture

Before the execution by the “Maquis Chabanne” of the seven inhabitants of Couture, the priest of Saint-Front, Father Albert Heymès, went there and expressed his feelings in a form I have been unable to determine. As a priest serving several parishes, he was coming from celebrating Mass in one of them; and it was on the return journey, at Saint-Front, that he was presumably stopped, along with his servant, Joséphine, and taken by truck to André Chabanne’s command post at Chatelars, an estate “the Priory” flanked by the remains of an abbey (not to be confused with “Le Logis du Chatelars,” which is a château). It was his misfortune that Albert Heymès was a refugee from the east of France and spoke with a strong German accent. He was born on 4 November 1901 at Kappelkinger, near Sarralbe, in Moselle.

At Colmar, François-Abraham Bernheim, still living, told me concerning him:

Heymès, I knew him well in 1936 and then in 1939 at Altrippe (where he was the priest). I lived in his village. He spoke the patois of Lorraine, the worst of the German dialects: the “paexer“; originally it’s Luxemburgian (that dialect, it’s enough to sicken you). Heymès was a bit ponderous, a bit coarse. He was not unlikable but he had a bad PR. (I don’t know anything about his death.) I suppose he fell on his back when he was struck and presumably split open the back of his skull. I was the judge. There was no lawyer. I made an impression because I didn’t shout. A man blenches and his eyes glitter, when you tell him he’s going to die.

For some inhabitants of the Moselle region, the former priest of Altrippe was intelligent, a musician, a big talker with an irritating style. “If he had stayed in Lorraine, it would have been the Germans who’d have cut off his head.”

M. was a member of the maquis and saw the truck arrive with the priest: “They didn’t set up the steps for him. That struck me. You have respect for a priest as you do for a teacher. He had his prayer book. He appealed to the good Lord for help … But he confessed that he was a member of the Wehrmacht [sic].”

M., of Chasseneuil, told me: “It wasn’t a pigsty they put him in, but a shed for sheep. They made him carry stones. A maquisard said to me: ‘This one will be good for making a beef stew tomorrow.’ He said that to me on a Thursday; well, Sunday it was he, the maquisard, who had been killed. This priest was a noncom in the German army.”

G., of Cherves, stated to me: “I saw him carrying very big stones and beaten by his guards. He had tears in his eyes.”

Two brothers took a leading role in the torture. I found one of these brothers, a tradesman, at Gond-Pontouvre, a suburb of Angoulême. I told him the results of my investigation. He stated to me: “He was tortured very severely but there was neither a rope nor a hot iron. When I came back with X. to the pigsty where the priest was, we found him motionless. We lifted his eyelids. We verified his death and concluded that he must have committed suicide with a ring.”

And, as I asked for an explanation of the ring, the man answered: “I refuse to say anything more about it to you. I won’t say any more about it unless Bonnot is willing to talk. See Bonnot.”

This last, a well-known official of the “Maquis Chabanne”, refused to give me any information.

The priest’s family refused to reply to my questions for fear of dealing with someone who was perhaps seeking, in the terms of a letter dated 2 June 1974, to “go along with the anticlerical propaganda of the age.”

Albert Heymès died on or about 11 July 1944; he was 42 years old. His body was buried in the cemetery of Cherves-Chatelars. His name is graven in the stone: “Father Albert Heymés [sic] / 1901-1944.” The bishopric of Metz did not desire exhumation and transfer of the body to Lorraine. The grave is totally neglected. His servant, Joséphine Adam, was executed on the 1st of August, together with another woman. At Chatelars I was often told she “cried a great deal.” They had made her wear a placard reading: “Priest’s wife.”

Nowadays the children of Cherves-Chatelars and the region are nurtured on the hallowed history of the Resistance. A plaque which indicated the dates of the birth and death of André Chabanne has been replaced with another no longer indicating the dates, giving the impression that the hero died in the war, whereas he died in an accident in 1963. Directly in front of the dwelling called “the Priory,” in which Father Albert Heymès was tortured to death, and where many other persons had been imprisoned or tortured or condemned to death, schoolchildren have planted a fir tree. A plaque reads: “Tree planted 3 September 78/ by the children of Cherves-Chatelars in memory of the “Maquis Bir Hacheim” /AS 18/ which was formed in this place/ in September 1943.”

In the schoolyard of the Cherves school there is a playground. On the playground’s exterior wall, along the road which leads from Cherves to Chasseneuil, there can still be clearly seen, more than forty years after the events, bullet marks: it was here that the three German soldiers were executed. Upon being informed of this execution, André Chabanne flew into a rage. He remembered, he said, that, taken prisoner by the Germans in 1940, he had escaped and been recaptured; his life was spared.

Nevertheless, ten years after the execution of the three Germans, André Chabanne had left their cadavers to lie in a nearby pond, “chez Veyret.” Neither the owners of the pond, nor the mayor of Cherves, nor the gendarmes dared intervene for them to be given a burial. Today ten or so bodies are still buried in the “foxholes” at the old Jayat mill, for exhuming them would mean exhuming a part of the truth in contradiction to the legend that grows stronger year by year. Even at Saint-Front, I interrogated a group of four women, the oldest of whom was a young child in 1944. I asked them what they knew about Father Heymès, their former village priest. The oldest one answered me: “That priest was no priest. The Germans put him there to keep an eye on us. He was there to spy.” Two of the other three women approved. Other people told me: “He wore a German uniform under his cassock”; or again, “A fine priest, he was! Under his cassock he wore the uniform of a captain in the SS.”

It is not difficult these days to find historians of serious repute who peddle even worse nonsense than that. It may nonetheless be true that Albert Heymès had served in the German army in the course of the first World War, during the period when his native province was part of Germany.

From The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 12, no. 1, Spring 1992, pp. 5-30.

_________________

[1] [The Milice (French: Milice française) was founded as an anti-maquis force by military hero (in both world wars) Joseph Darnand in January, 1943. – Ed.]

[2] Pronounced Savignat, in keeping with the original spelling. A century ago a great many place-names of the region found themselves bearing the suffix -ac instead of the suffix -at.

[3] A member of the maquis.

[4] After the confiscation of his camera, valued at 60,000 francs, he was to have no choice but to join the Maquis. He was killed in the Royan pocket.

[5] Anna was to testify to this after the war to the investigators of the Sécurité militaire.

[6] Louise V. lives today (1974) in Limoges, where she married a hairdresser. She has two daughters, one of whom is a teacher and the other an engineer (elsewhere than at Limoges). Her father was a Communist.

[7] After the war, investigations of the Sécurité militaire will establish facts of this sort. Cécile Armagnac disclosed to us that it was out of concern not to excite bitter feelings that Madame Armagnac waived the return of the property (“… anyway, that would not have brought Françoise back to us”); as for the other property, the indemnity collected by Madame Armagnac seems to have been very modest.

[8] The special Algiers legislation, like the appeals of Radio London and in particular those of Maurice Schumann, sanctioned, it seems, this kind of distinction.

[9] In 1944 France was on Central Europe time: 9 p.m. thus corresponded to 7 p.m. solar time.

[10] The persons questioned, including those most hostile to the Militia, told us emphatically that Françoise Armagnac seemed to them incapable of making any such remarks, either in substance or form. We state here that witness Lindner seemed to us subject to grave shortcomings on points other than just the “Armagnac Affair.”

[11] This mention of Signal is astonishing. Even more astonishing is the comparison with Match (or Paris-Match). Signal was a weekly of very good quality but one that many French people refused to buy on account of its German and National Socialist character. Yet Nathan Lindner was selling it, or trying to sell it, in Chabanais. The sale of it was not compulsory, of course, any more than was its purchase. Françoise Armagnac had forbidden the children she looked after to buy anything at all from Trottinette, who was guilty, in her eyes, of selling Signal as well as publications of a licentious nature.

[12] In all probability these armbands and insignia were… Scout insignia (with the exception of that found in the little clog).

[13] A probable confusion with the insignia found in the little clog.

[14] According to her sister Cécile, Françoise, receiving no response – the mail was operating under precarious conditions – made her decision without waiting any longer.

[15] This confusion seems to have been produced elsewhere in France; see also the confusion between “cheftaine” and “chef de centaine”; that is to say, between a Scout rank and a rank in the Militia!

[16] These two last phrases offer an example of the contradictions that we sometimes encountered in the course of our inquiry when a witness attempted to formulate a general judgment.

[17] We relate this matter only to give the reader an idea of the conviction of certain witnesses. As was to be revealed later, G.B. was not present at that scene, despite his claim.

[18] Françoise Armagnac was never the secretary of the Militia of Confolens. The sentiment the witness attributes to her is unlikely for someone who had broken with the Militia by sending in her resignation eleven months previously. As for the extreme brevity of this testimony, it is due to the fact that at the time of our meeting with “Bernard” we had not yet gathered much information about the executions and, in particular, about this one.

[19] “Gaston,” or Jean T. by his true name, nowadays lives near Saint Victurnien (Haute-Vienne). Françoise was not a chef de centaine but a cheftaine. The witness is confusing here a modest rank in the Girl Scouts with an important rank in the armed Militia!

[20] The attentive reader will be able to point out half a dozen errors in this summary of the affair. These errors may be explained by the fact that Robert Aron, who is a generalist, could not devote himself to exhaustive verification of each case. Some of the errors are perhaps also to be accounted for by the force of attraction of certain clichés or stereotypes that call for one another and give the story the stark simplicity and dramatic color that are to the taste of certain readers of novels: “acts of violence… detestable… descend upon women… young woman… Mlle d’Armagnac [sic]… family… proprietor… château… gets married… church… her village… coming out of the mass… parvis… kidnapping…” In a context like that, we are not too much surprised to see the execution take place “the next day at dawn” (whereas, it will be remembered, François Armagnac, interrogated several times on the day following her arrest, was not executed until nine p.m.).

[21] We are correcting the accentuation, but not the spelling or the punctuation of this document, every sentence of which would merit an attentive reading.

[22] In fact, it was not Petit Chevrier but Bel Air.

[23] The correct spelling is Aubineau.

[24] For the burial of the “Spaniard”, the two Devoyon brothers, of Chabanais, had made a coffin for him that was considered too short; they were both executed.

[25] Pseudonym of Nathan Lindner.

[26] Cécile Armagnac, to whom we showed this document in 1975, deems it suspect. She cannot imagine that her mother could put forward a claim of that kind within two or three days after the arrest of Françoise and the “removal” of Bel Air.