The origin of the myth. The myth of the “gas chambers” dates back to 1916

The myth of gassings of Jews during the Second World War is merely the product of a recycling of the myth of the gassing of Serbs during the First World War. It may rightly be said that a myth seemingly born in the early 1940s and, today, fifty years old thus goes back in fact to 1916-1917, and is therefore seventy-five years old.

However, it is possible that it goes back a good deal further. Perhaps the original trace of mythical gassings is to be found in stories of the war in the Vendée region of France during the Revolution or, further still, even before the invention of the word “gas”, in times when a supposed mastery of the Earth’s obscure forces was thought to enable murder by “subtle substances” or “invisible vapours”. Does not a myth always plunge into the farthest depths of man and his memory?[1]

In 1916-1917 the Allies spread about the tale of Serbs being gassed systematically and in large numbers by the Germans, the Austrians and their Bulgarian allies. The gassings were reportedly taking place in delousing facilities, churches and other places. This canard disappeared after the war, as from the beginning of the ’20s. Likewise, other inventions of Allied war propaganda vanished, at least apparently: the legends of Belgian children with their hands cut off by the Uhlans (forerunners of the SS) and of corpse factories where the Germans were said to turn human fat and bones into fertiliser and soap (forerunners of the “extermination camps” in the service of Hitlerite science said to produce fertiliser and soap from the corpses of Jews).

These war canards’ success was probably fuelled by the spectacle of quite real atrocities: the ravages wrought by the use of poison gas on the battlefields and the piles of bodies of typhus victims, in Serbia in particular.

The myth of the gassing of Jews from 1941 to 1944 (or 1945) ought to have disappeared after that war as well. However, it still persists today. People’s minds are still being fed with it. By dint of the publicity it receives through the media, this invention of the Allies’ war propaganda has, with time, become a product of forced consumption. This product is spoiled. Although under new packaging, it is nothing but wares launched on the market in 1916-1917 and, since the ’20s, acknowledged as being tainted. But this hardly matters. In France, since 1990 and the entry onto the statute books of the Fabius (alias-Gayssot) Act, it has been forbidden to dispute the quality of this commodity and denounce its producers and vendors. One risks prison if, mindful of both honesty and hygiene, one tries to warn consumers against the noxiousness of these products that, backed by huge financing, invade the book market, television and the schools. Nonetheless, this law has some strange effects. In obliging us to believe in the gassings of Jews during the Second World War, it also forces us, in a way, to believe, anew, in the gassings of Serbs during the First World War. It thus rehabilitates a very old lie that seemed to have had its day. This is what is called the irony of history.

The three items presented below show how the shift from the myth of gassings of Serbs to the myth of gassings of Jews happened. The first piece is taken from a book in which a former correspondent and collaborator of the Frankfurter Zeitung tells incidentally of an interview given to him in Berlin on November 20, 1917 by Richard von Kühlmann (1873-1948), Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. It will be noted that the German statesman, exasperated by the behaviour of his Bulgarian allies, seems disposed to welcome any canard about them from the Allies. Thus it is that he believes the Bulgarians are carrying out a policy of physical extermination of the Serbs (“genocide” before the term existed) and that, under the pretext of hygiene, those Serbs are being led into delousing facilities in which, in fact, they are gassed (foreshadowing the story of Jews led, under the pretext of delousing and showering, into buildings where they are gassed).

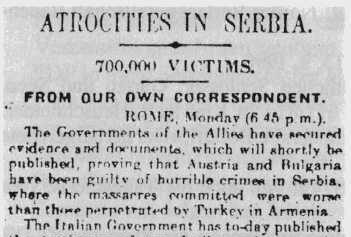

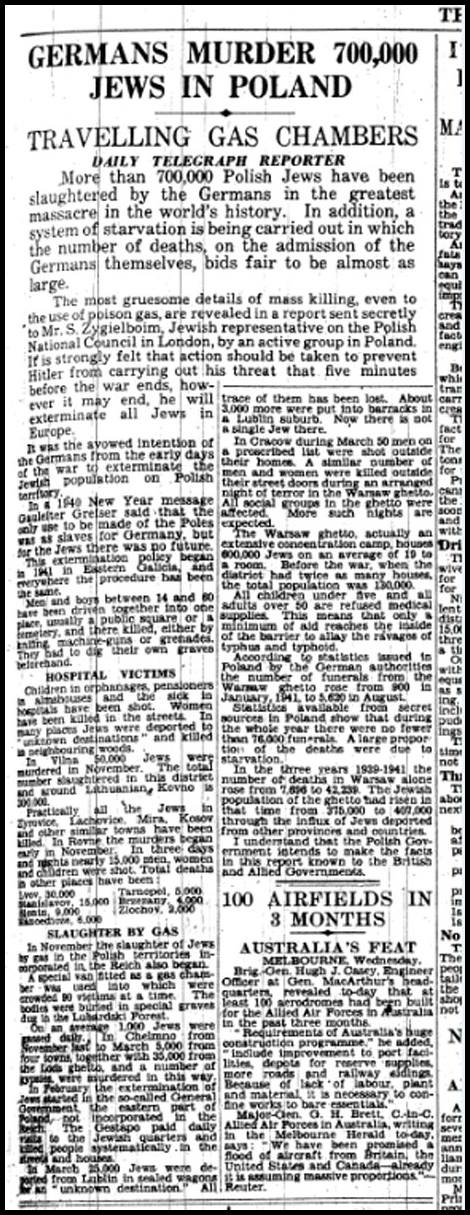

The two other items are both taken from the same London newspaper, the Daily Telegraph. On two dates twenty-six years apart that paper has used the same figures: on March 22, 1916 it announces the murder of seven hundred thousand Serbs and, on June 25, 1942, it headlines the murder of seven hundred thousand Jews. In 1916 the public are told that the Germans, Austrians and Bulgarians are “exterminating” (that is the word) the Serbs in different ways and, particularly, by means of asphyxiating gases either in churches or in other, unspecified places; these gases emanate from bombs or gas-producing machines. In 1942 the newspaper wants us to believe that the Germans are “exterminating” (still the word) the Jews in many ways and, particularly – this is the modern aspect – by using one, and only one, “van fitted as a gas chamber”, which eliminates no fewer than a thousand Jews daily.

30 novembre 1991

________________

Item 1 [translated from the German]

[…] The State Secretary [for Foreign Affairs, Richard von Kühlmann] is of grave and sombre mood. Peace seems far off. He has doubtless harboured many illusions about England’s desire for peace. All our allies instil in him a deep mistrust. The Bulgarians are insatiable; when given a jacket and trousers, they ask you for a shirt and shoes. He tells of how they are systematically “liquidating” the Serbs [word for word: auf dem Verwaltungswege – by bureaucratic means]; under the pretext of hygiene, the latter are led into delousing facilities and, there, are eliminated by gas. This is the future, he adds, of the battles between peoples.[2]

________________

March 22, 1916

________________

June 25, 1942

____________________

Notes