The Auschwitz-I swimming pool

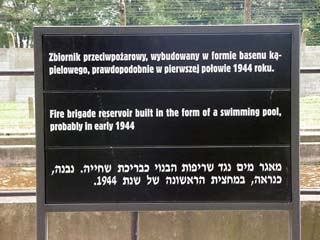

The German-Australian revisionist Fredrick Toben has brought to our attention the fact that today, beside the swimming pool at Auschwitz I, there stands a signboard bearing, in Polish, English and Hebrew, a notice intended to have the visitor believe that the pool was in fact a simple reservoir for the fire brigade. It reads as follows:

Fire brigade reservoir built in the form of a swimming pool, probably in early 1944

He asks when exactly this signboard appeared. I myself have no idea but the inscription is just as fallacious as any number of the Auschwitz museum’s other allegations or explanations. One fails to see why the Germans, rather than settling for an ordinary reservoir, would have made one in the fashion of a swimming pool… complete with diving board.

The pool was a pool. It was meant for the detainees. Marc Klein mentions it at least twice in his recollections of the camp. In an article entitled “Auschwitz I Stammlager” he wrote:

The working hours were modified on Sundays and holidays, when most of the kommandos were at leisure. Roll call was at around noon; evenings were devoted to rest and to a choice of cultural and sporting activities. Football, basketball, and water-polo matches (in an open-air pool built within the perimeter by detainees) attracted crowds of onlookers. It should be noted that only the very fit and well-fed, exempt from the harsh jobs, could indulge in these games which drew the liveliest applause from the masses of other detainees (De l’Université aux camps de concentration : Témoignages strasbourgeois, Les Belles-lettres, Paris 1947, p. 453).

In his booklet Observations et réflexions sur les camps de concentration nazis, he further wrote:

Auschwitz I was made up of 28 blocks built of stone laid out in three parallel rows between which ran paved streets. A third street ran the length of the quadrangle and was planted with birch trees, the Birkenallee intended as a walkway for the detainees, with benches; there also was an open air swimming pool (booklet of 32 pages printed in Caen, 1948, p. 10; its text is a reproduction of the author’s article published in Études germaniques, n° 3, 1946, p. 244-275).

M. Klein, professor at the Strasbourg medicine faculty, took care to point out that his first statement had been submitted “to the reading and scrutiny of Robert Weil, professor of science at Sarreguemines lycée,” who had been interned in the same camps as himself (p. 455).

In 1985, at Ernst Zündel’s first trial in Toronto, I spoke of M. Klein’s recollections but the real specialist on the history of the Auschwitz I swimming pool was at that time none other than the Swedish revisionist Dietlieb Felderer. If I remember correctly, the Canadian press headlined an article on his testimony about it. Moreover, in his writings he often returns to this and other quite concrete, quite precise subjects just as disquieting for the supporters of the exterminationist argument.

NB: The water of the swimming pool can obviously be used by firemen in case of emergency. In his booklet, M. Klein wrote that “there were firemen at the camp with very modern equipment” (p. 9). Amongst the things that he had not expected to find on arriving, in June 1944, “at a camp whose sinister reputation was known to the whole world thanks to the Allied radio broadcasts,” one may note, for the detainees, “a hospital with sections specialised in line with the most modern hospital practices” (p. 4), “vast and well fitted-out wash houses along with communal W.C.’s built according to the modern principles of sanitary hygiene” (p. 10), “the micro-wave delousing process which had just been created” (p. 14), “the mechanical bakery” (p. 15) the legal aid for the detainees (pp. 16-17), the existence of “dietetic cooking” for some of the sick, with “special soups and even a special bread” (p. 26), “a library where numerous reference works, classic textbooks, and periodicals could be found” (p. 27), the daily rolling by, next to the camp, of “the Krakow-Berlin express” (p. 29), a cinema, a cabaret, an orchestra (p. 31), etc. M. Klein also notes the horrible aspects of life in the camp and all the rumours, including the “horrific stories” of gassings which he seems not really to have believed until after the war, and then only thanks to the testimonies in the “various trials of war criminals” (p. 7).

July 20, 2001

Addendum of 27 July. A wartime detainee and, like M. Klein and R. Weil, a Jew himself, confirmed, in a short testimony written in 1997 entitled “Une Piscine à Auschwitz,” that he saw, in July 1944, dozens of his fellow prisoners busy at work on the said pool which, he pointed out, had “a diving board and an access ladder”; he could have added “along with three starting blocks for races.” He wrote that towards the end of that month “a newsreel director had some deportees filmed swimming there.” As one might expect, he enlivened his account with the regular stereotypes of the SS men’s or kapos’ brutality and he saw in the making both of the pool and of the film nothing but a propaganda operation. His report ends with two interesting remarks. First, that in 1997 no guide was “aware” of the pool (which nonetheless was before the guides’ very eyes and of which a photograph accompanies the article: we read that this picture, showing a swimming pool full of water, was taken in that year) and that the author would like to know just where the newsreel might be today. His question is akin to those put by some revisionists: might the film not be “at the headquarters of the International Red Cross”? Doubtless he meant: at the International Tracing Service (ITS) located at Arolsen-Waldeck in Germany and operating under the direction of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), with headquarters in Geneva. Since 1978 this body has barred revisionists from its archives, which are known to be an exceptionally rich resource. For its part, the Auschwitz State Museum probably possesses documentation relevant to various aspects of this swimming pool’s construction, e.g. the project, the plans, the financing, the requests for and supply of building materials, the requisition of labourers, the inspection visits.

(Reference for this account: R. Esrail, registration no. 173295, “Une piscine à Auschwitz”, in Après Auschwitz (Bulletin de l’Amicale des déportés d’Auschwitz), n° 264/octobre 1997, p. 10).