Daily life of German Jews during the war (Three documents)

By Célestin Loos

(in reality, the late Pierre Moreau (of Brussels) and Robert Faurisson: article published in the Revue d’histoire révisionniste, no. 6, May 1992, p. 131-140)

It is well known that in March 1933 worldwide Jewish organisations declared economic war on Germany. In September 1939 Chaim Weizmann declared armed warfare. In Europe during the war years Jewish resistance – especially in association with the communists – was active. To take just one example, on May 13, 1942 eleven Jewish communists belonging to the Herbert Baum group and the Werner Steinbrinck group (also called “Franka Group”) carried out an arson attack on the exhibition “The Soviet Paradise” at Berlin’s Lustgarten. Five German civilians were killed in the fire.[1]

The Germans considered the Jews as a whole to be representatives of a hostile belligerent power, all the more formidable since, internationally, it disposed of considerable resources in the field of finance (money, the sinew of war) and in those of the communications media and propaganda. Physical attacks engendered reprisals, which in turn gave rise to new attacks. Just as the Americans or the Canadians, considering persons of Japanese descent dangerous or hostile, decided – notwithstanding the absence of attacks or sabotage on their part – to place them in concentration camps, the Germans proceeded to evacuate large numbers of German Jews, putting them in concentration, labour or transit camps. However, a certain Jewish life subsisted openly in Germany all through the war. The three documents below make it possible to provide a sketch of that daily life: a newspaper, an excerpt from the telephone directory, a ration card. Obviously, the longer the war went on the further that daily life deteriorated, as did, for that matter, the lives of other Germans.

A newspaper

The first is the weekly Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt [“Jewish Information Bulletin”], which was published altogether legally during the Second World War for German Jewish religious communities. It must be stressed that this newspaper was perfectly official, with its title, address and telephone number included in the telephone directory. Its offices were in Berlin N4, Oranienburger Straße 40/41. One gets the impression of a well-structured organisation and of social autonomy, a community suffering vexations but not finding itself in a tragic situation: things often seem even peaceful, considering the period and the taxing disruptions endured by the rest of the German population. Because of the shortage of paper, all German newspapers saw their dimensions shrink. Such was the case of the Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt in January 1943, and its last issue appeared in December of the same year.

Let us analyse issue number 23 of 1942, dated June 5.

There are announcements of services to be held in nine synagogues in Berlin for the week of June 5-12. Also, the Jewish religious calendar for the corresponding week, running from the next sabbath day, i.e. “Siwan 21 to 28, 5702”. Also, a notice concerning the providing of Jewish funeral services, with the hours of availability of different telephone numbers. Worship activities in two other cities, Frankfurt am Main and Hamburg, are announced.

The death in Berlin, at the age of 86, of a well-known figure from Dessau is the subject of a special feature: it is the former banker Paul (Israel) Märker. “Mr Märker,” it reads, “was for several decades treasurer of the Cohn-Oppenheim foundation and a member of the governing committee of the Dessau community. He rendered great services to the Jewish community”.

For the town of Rheydt we have news of the golden wedding anniversary of a couple “highly esteemed amongst the Jews of the region. In particular, Mr Spier has distinguished himself by graciously fulfilling the function of cantor, thus enabling religious ceremonies to be maintained”.

The main article of Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt consists of a purely technical presentation of the new legal provisions on the voluntary resignation of members of Jewish communities, which could take place only within narrow limits. Another piece announces the obligation for Jews to use only Jewish hairdressers.

For the rest, there are notices and advertisements, which shed light on the daily life of Jews in 1942 Germany.

Family announcements first. A wedding to be held on June 7. Newlyweds respond to their well-wishers. A young boy thanks those who congratulated him on the occasion of his barmitzva. Silver wedding, golden wedding anniversaries. Birthday celebrations of persons ranging in age from sixty to ninety. Then the obituaries of individuals, most often of an advanced age, others younger, “after a long and harrowing illness”. One lady and another “have gone to a peaceful slumber” [sanft entschlafen].

In short, in the midst of war, the joys and sorrows of normal life.

There are other more prosaic advertisements. A Jewish bookshop [Jüdischer Buchvertrieb] publicises several titles: a biography of Theodor Herzl, the father of Zionism; another of Moses Hess, founder of modern socialism; yet another of Chaim Arlosoroff, Zionist activist assassinated in 1933 (in Tel Aviv). It also sells second-hand books, over the counter or by post. Payment is to be made either on collection or with the order, but delivery by return post is not guaranteed.

A lady, “qualified teacher”, offers private lessons in English and French. A music teacher who gives his lessons only in people’s homes. Persons looking for a guesthouse run by a Jewish family. Advertisements of premises to let, furnished or unfurnished, and others placed by individuals seeking to rent.

Practitioners of the art of healing – doctors, dentists, physiotherapists – are required to specify that they are authorised to treat Jewish patients alone, but they are able to publicise their practice. They have an advertising section reserved for them called “Health Care”, wherein each gives, along with days and hours for consultations, an address and telephone number. Dr Jacob Wilmersdorf, Badensche Str. 21, II (corner of Kaiserallee), tel. 87 70 28, receives visits from 10 am to 12 pm and from 4 pm to 7 pm except Mondays and Wednesday afternoons; Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings by appointment only. Dr Berthold Alexander, radiologist, receives patients at such and such hours at Augsburger Straße 19, mornings and afternoons (even on Sundays, if one understands correctly), but on Saturdays only in the morning. Dr Leopold Berendt, Friedrichstraße 3, also receives patients on Wednesday and Sunday mornings and Saturday afternoons, but only by appointment. Similarly, Dr Herbert Rittler offers consultations by appointment at Markgrafenstraße 20, except on Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings. Sally Rosenthal is a physiotherapist and dispenses medical massages and localised light-baths, by appointment and on Saturdays from 10 am to 2 pm, in Neuen Roßstraße. And she is accredited by all the health care funds reserved for Jews [Zu allen Krankenkassen visible to zugelassen Juden]. “I have re-opened my practice,” announces Dr Max Brandenstein (Hamburg, Bundesstraße 35a, ground floor), who may be reached on the telephone at 55 71 50 care of Siegmund Elias (this advertiser had had some difficulties – of what kind no one knows – but his situation was, it seems, finally returning to normal).

“Conscientious and affectionate” care is offered for convalescence holidays for two or three children aged up to six, who will be collected and returned home.

Such was Jewish existence, seen in real-life snippets, in the capital and in some other big cities of the Reich in the middle of the war. There existed an information bulletin whose readers took advantage of it to communicate with one another. Whatever its importance or however derisory its content, one must be allowed to take note of it, without making any assertions, without forcing conclusions.

A telephone directory

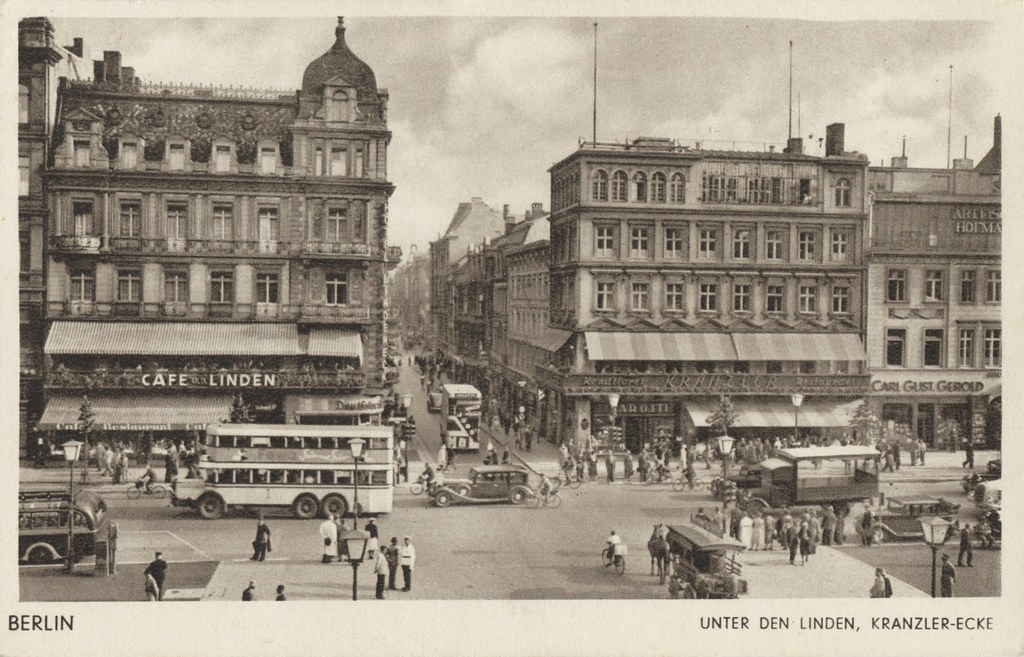

Another interesting piece comes from a telephone book with the full title: AMTLICHES FERNSPRECHBUCH für den Bezirk der Reichspostdirection BERLIN – Herausgegeben von der Reichspostdirektion Berlin / Ausgabe Juni 1941 / Stand vom 1. Februar 1941 [Official Telephone Directory for the Berlin postal sector – published by the Berlin directorate of the Reich post office / June 1941 edition / Information as at February 1, 1941].

On pages 581 and 582 appear the numbers to dial for the capital’s Jewish associations. There are two and a half columns of dense print, listing the various centres, their addresses, activities performed, services available to members. Below are the contents of the first part of the first section, that of the Jewish religious Federation: Jewish Communities of Berlin, registered firm [Jüdische Kultusvereinigung: Jüdische Gemeinde zu Berlin eV. (eingetragener Verein)]:

– Administrative buildings N4 Oranienburger Str 28, 29 and 31 –

*42 59 21.

At that number the following offices may be reached:

Archives – Construction – Receipts – Financial Management – Property Management – General Management – General accounting – Central fund – Land registry – Religious services and weddings – Equipment – Personnel – Press – Legal department – Revision service – Schools department – Bureau of statistics – Winter relief – Housing support – Central service of homes for the aged.

Evening and night:

Plörin, Oranienburger Str 29 (42 94 27).

Council Chamber of the Presidency (42 94 30).

– Administrative buildings N4 Oranienburger Str 31 –

*42 51 31.

At that number the following offices may be reached:

Office of emigration – Change of trade and social service – Arbitration and legal advice – Aid to the homeless – Aid to businesses (money).

Employment and services for foreigners (42 51 31).

*42 63 96.

The foregoing lines amount to only a bit more than 13% of the space in the directory reserved for Jewish associations connected to the Berlin telephone network in 1941, thus in the middle of the war.

Let us draw up a list of these entries, showing the complexity of the Jewish social structure at the time in the Reich’s capital alone. The list is not exhaustive because some entries are repeated in the various sections:

Schools administration – Aid to businesses (fund) – Housing aid – Aid to prisoners and to the homeless – Children’s aid – Arbitration and legal advice – Archives – Aid to the sick – Association for Jewish culture in Germany – Administrative buildings – Charity and protection of youth – Bureau of statistics – Construction office – Office of religious services and weddings – Land registry – Central fund – Clothing – Cemeteries (inspection of) – Private Jewish clinic – General accounting – Community kitchens – Housekeeping school – Primary school (boys) – Primary school (girls) – Private tertiary school – School of commerce – Vocational school for fashion design and decoration – Chemistry school – Housekeeping school – Middle school – Primary schools (eight addresses) – Employment and services for foreigners – Receipts – Gravediggers – Jewish National Fund (registered firm) – Home for nurses – Home for Jewish schoolteachers – Home for girls – Financial management – Property management – Home for ladies and girls – Home for Jewish youths – Old people’s care home – Home for Jewish infants and small children – Home for the sick – Home for children and adolescents – Children’s homes (three addresses) – Hospital at Auguststr. 16 – Hospital at Elsasser Str. 85 – Hospital at Iranische Str. 2 – Hospital at Schulstr. 78 – House of education – Stylz home for the blind – Home for deaf-mutes and the hard of hearing – Employment and services for foreigners – Nationalfonds (registered firm) – Office of emigration – Old men’s boarding house – Welfare service [Bereitschaftsfürsorge] – Resident population [Insasse] – Protection of youth – Professional reclassification and social service – South residence – North residence – Weißensee residence – Central residence – Children’s reading room – Winter relief – Jewish seminary for kindergartens and nurseries – Press – Revision – Schools – Equipment – Health – Press – Immigration – Schools – Central service of homes for the elderly – Dues/Contributions – Legal department – Personnel – Equipment.

There can be little doubt that the Jewish population established in Germany possessed its own legally recognised institutions. Their official status reflects the authorities’ position regarding them, but it was also perfectly consistent with the state of mind of the German population, as witnessed in late 1941 by the American Jewish journalist George Axelsson. While on a working visit to Germany he cabled a report to his newspaper, the New York Times (published on November 10, 1941 – page 31), about the Reich and the more than 200,000 Jews who were still there. He concluded it in these terms: “In public places or in contacts as a fellow-worker in factories the German working man seem to treat the Jew as an equal.”[2] All this is hardly compatible with the usually presented image of Jews in Germany at that time. We see something quite removed from a hunted horde, uprooted, with no recourse of any kind, no possessions, no rights. Such a lot was not that of the Jews in general, but was indeed one which millions of Germans were to have to endure from 1945 onwards. In the public mind a propaganda-induced substitution has been quite easily effected: the often fictitious destitution of the Jews under the Reich for the destitution, all too real, inflicted on the Germans, especially the deportees driven from their homes in the East in 1945 and afterwards. Some will surely retort that the directory in question here dates from 1941 and that all the organisation reflected therein was to be reduced to naught soon afterwards. That seems not to have been the case. The International Committee of the Red Cross published just after the war a book on the German concentration camps: L’Activité du CICR en faveur des civils détenus dans les camps de concentration en Allemagne (1939-1945) [3rd edition, Geneva 1947]. On page 103 appears one of its delegates’ report, dated April 16, 1945, on his talks with SS-Obergruppenführer Müller of the SS-Führungshauptamt. It contains this sentence:

On the other hand [Müller] allowed me to place the Jewish assembly camp at Schulstrasse 78 in Berlin, as well as the Jewish hospital at Iranische Strasse 2, also in Berlin, under ICRC protection.[3]

Both addresses appear in the list that we gave above and are, effectively, those of two hospitals that still stood as Jewish property at the end of the conflict. One would like to know what became of the other two, along with the rest of the Jewish community’s properties. It is not rash to think that a good part of them, like thousands of other buildings, lay in ruins in heavily bombed Berlin.[4]

A ration card

But is it at all likely that something of a Jewish administration and, for that matter, some Jewish civilians still survived in Germany at war’s end? An element of response is provided on page 324 of Gérard Silvain’s book, La Question Juive en Europe, 1933-1945[5]. Under the facsimile of a document the author put this caption:

1945

Adult’s food ration card (prime necessities).

The word “JUDE” has been set not only on the card but also on the coupon.

Between February 5 and March 4, 1945 were there still Jews living in freedom in German territory?

This card, from which the coupons have been detached, proves that it has been used and thus allows one to answer in the affirmative.

In fact, the period of validity of the card shown ran from February 5 to March 4, 1945, and the supplies office having issued it was that of Munich. It is indeed the case that not only the card but also the coupons bore the word “JUDE”, applied not by means of a stamp but printed, which means that the number of addressees of these cards was large enough to justify printing. Such printing therefore had to be planned. The ration cards were not handed out right and left but, as one will hardly doubt, dispensed on the basis of carefully drafted name lists. Have those lists all disappeared from all the German cities’ archives? That is difficult to believe. Thus the question arises: why are they not produced?

Besides, the Jews are above all city-dwellers and, as such, were particularly vulnerable since the Allies were, in the main, bombing only the cities. How many of them died as a consequence, burned in their houses? Unless we are mistaken, that has never been disclosed but, here again, confirmed figures must have survived.

In some cases Jewish children were sent to the countryside to escape the bombing; so it was with Lea Rosch, today a leading German television personality.

The period from February 5 to March 4, 1945 was that of the bombing of Dresden (February 13-14). The Allies were killing German civilians by fire. The Germans, as we see, were feeding Jewish civilians.

In May 1945 the Soviets installed Dr Werner as head of the municipality of Berlin. They asked him to create, within the city council, a religious services body made up of a Catholic priest, two Protestant pastors and a rabbi representing, for his part, the 6,000 Jews of the city (Georges Soria, L’Allemagne a-t-elle perdu la guerre ?, Bibliothèque française, Paris 1947, p. 23).

May 1, 1992

______________

Notes

[1] See Eliyahu Maoz, “Une Résistance juive en Allemagne”, Commemoration of the ghetto revolt, Jerusalem, March 1965, 15 pages produced in photocopy by the organisation department of the World Zionist Organisation; see also the article “Berlin” in the Encyclopedia Judaica (1971).

[2] Quoted by James J. Martin, The Man Who Invented Genocide / The Public Career And Consequences of Raphael Lemkin, Institute for Historical Review, Torrance, Calif. 1984, p. 35. On the exact condition of the Jews working alongside German workers at Fürstengrube, one of the 39 auxiliary camps of Auschwitz, one may read the astounding document NI-10847 translated, rather poorly, in La Persécution des juifs dans les pays de l’Est présentée à Nuremberg, a compendium of documents published under the direction of Henri Monneray, Editions du Centre [de documentation juive contemporaine], Paris 1949, p. 201.

[3] “The Jewish hospital, directed by Dr Walter Lustig, was in operation up to the end of the war. […] The Jewish cemetery in Weissensee was also functioning” (Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, 1990, p. 202).

[4] On November 24, 1943 a British aerial bombardment destroyed the “New Synagogue” of Oranienburgstrasse 30. The photograph of that synagogue in flames has, since 1945, circulated throughout the world with the following explanation: the synagogue was destroyed by arson, imputable to the Nazis, during the Kristallnacht of November 8-9, 1938. Not long ago the German post office published a postage stamp presenting that version of the facts, also repeated recently in the French daily Le Monde (Frédéric Edelmann, “Le Souvenir d’une négation”, February 8, 1992, p. 17). However, in 1987, a publication of the Berlin Jewish community, prefaced by its head Heinz Galinski, had admitted the truth (see the brochure Wegweiser durch das jüdische Berlin – “Guide to Jewish Berlin”).

[5] Éditions Jean-Claude Lattès, Paris 1985.